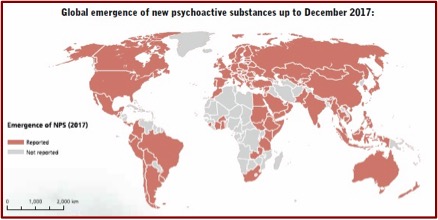

New/novel psychoactive substances (NPS) continue to grow in number at the rate of about 100 new ones each year. As of December 2017, there were more than 800 NPS substances reported to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) Early Warning Advisory on NPS. Sometimes they are called “legal highs” because they are substances of abuse not controlled by either the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs or the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances. Over 110 countries from every region of the world have reported one or more NPS. And you can’t always Ask Alice (or anyone else) to help you sort out what you’ve taken and how it effects you because there is very little known on their risk factors and long-term harm from their use.

UNDOC launched an “Early Warning Advisory” in June of 2013 to address the emergence of NPS at the global level. The goal of the EWA is “to monitor, analyze and report trends on NPS.” It also acts as a compilation of information on these substances. If you don’t know much about NPS, it’s a good place to begin your education on them. Information on the adverse health effects and social harms of NPS are often hard to come by, making treatment and prevention efforts difficult. The following graphic, found in the UNDOC Early Warning Advisory, illustrates how NPS have rapidly become a global concern over the past 10 years.

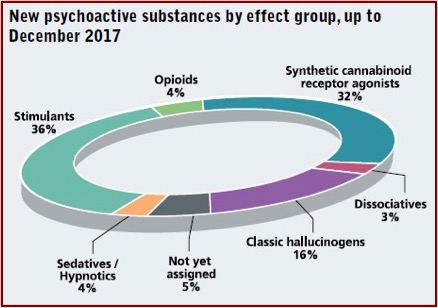

The majority of NPS are either stimulants (synthetic cathinones, methedrone, MDPV and others) or synthetic cannabinoids, followed by hallucinogens and others. The various NPS also include plant-based substances like kratom, khat and salvia (salvia divinorum). Fentanyl analogues (opioids) are a growing concern with 34 synthetic opioids registered in the EWA by the end of 2017. “In June 2018, UNODC launched an integrated strategy responding to the global opioid crisis.” The following graphic, also found in the UNDOC Early Warning Advisory, illustrates the main substance groups of NPS.

The Mental Elf posted an article, “Novel Psychoactive Substances: bridging the knowledge gap” by Derek Tracy, who said: “We are experiencing fast shifting sands in the world of substance misuse, with a clear current need to pitch some way-markers and determine research and clinical priorities.” NPS have altered how drugs are obtained, adding Internet and ‘dark web’ purchases to the traditional drug-dealing model. He said the vast amount of NPSs creates an enormous problem keeping up to date with the field. He pointed out there is no universally agreed way to categorize NPS. In two papers written for the BMJ, he and others suggested four major categories that combined benzodiazepine (sedatives/hypnotics) and opioids into Depressants and classic hallucinogens and dissociatives into Hallucinogens, while retaining Stimulants and Cannabinoids.

Tracy noted how the UK law, “Psychoactive Substances Act 2016,” was an attempt to restrict the production, sale and supply of NPS. The law defined a psychoactive substance as anything which “by stimulating or depressing the person’s central nervous system … affects the person’s mental functioning or emotional state”. The act makes it an offense “to produce, supply, offer to supply, possess with intent to supply, possess on custodial premises, import or export psychoactive substances; that is, any substance intended for human consumption that is capable of producing a psychoactive effect.” Exemptions included: alcohol, tobacco or nicotine-based products, caffeine, food and drink and medicinal products.

He also described the work of the NPS-UK project. which set out to summarize and evaluate what is known about NPS use, harms and responses; develop a conceptual framework for a public health approach; and make recommendations on evidence gaps and future priorities. “The authors systematically reviewed the existing literature up to June 2016, and used these findings to produce both the conceptual framework and key recommendations on future priorities.” They included 995 studies in their analysis. There was limited data on social and other risk factors, population risk factors, long-term harm, intervention effectiveness and treatment outcomes. The limited harms data available meant it was not possible to build a good population risk assessment. “The conceptual framework notes the need for better long-term data on harms and intervention effectiveness, and the wider societal burdens involved.”

NPS use remains a ‘minority’ amongst those who consume drugs, but the area is important. Some are being shown to be especially potent, with localised bursts of hospitalisations and deaths; the novel fentanyls seem a particular worry. Even more so than is usually the case, there are some very marginalised and vulnerable people who seem disproportionately involved, notably those who are homeless, in prisons, and forensic psychiatric units. Issues of detectability and cost may be playing a role, but when we think of the social space in which harmful drug use is treated and lives rehabilitated, these may be very difficult people to reach.

The World Drug Report 2018 said the NPS market continues to be dynamic. New substances emerge, while others seem to disappear after a short time. Around 70 of the 130 NPS reported when UNODC began global monitoring in 2009 have been reported every year since then. “On the other hand, about 200 NPS reported between 2009 and 2014 were no longer reported in 2015 and 2016 and may have disappeared from the market.” Yet this may not be accurate, given the complexity of identifying NPS in many parts of the world.

The comparison of epidemiological data on the use of NPS in different countries is not easy because the definition of NPS may differ from country to country and may include substances that have been placed under national or international control. There are limited data available to make comparisons of the prevalence of NPS use over time and limited survey tools for capturing NPS use, and NPS users have limited knowledge about the substances they use.

While the data on NPS trends is limited to a few countries, it seems in the past three years there has been a shift away from smoking herbal mixtures to using NPS in tablet or liquid form. In the U.K. NPS packaging changed after the new NPS legislation was implemented. Before they was in bright, colorful packages and gave the perception of being legal alternatives to illegal drugs. But since 2016 NPSs have been in plastic wraps or bags with no detailed information on what they contain. A disturbing trend is the pattern of NPS use among vulnerable and high-risk groups including homeless people and individuals struggling with mental health issues.

“The use of new psychoactive substances among homeless people has been documented in Czechia, Finland, Hungary, Ireland, the United Kingdom and the United States.” A study of 53 homeless people in Manchester England found that 79% had used NPS in the past year. Of those who reported using NPS in the past year, 64% said they used them daily, and another 14% used them five or six days per week. “Synthetic cannabinoids were the substances most often reported.”

In Scotland, 22% of admissions on general adult psychiatric wards between July and December of 2014 reported using NPS. A diagnosis of drug-induced psychosis was significantly more likely than depression among those reporting NPS use. Stimulant NPSs (analogues of amphetamine, methamphetamine, MDMA, methcathinone) were used three times more often than synthetic cannabinoids. A study in England found 12% of patients admitted to a secure mental health setting had used NPS beforehand. “About 20 per cent of mental health units had required an emergency response to assist with NPS use in the past 12 months.”

There are also increases in the use of benzodiazepine-type NPS and overdose deaths related to their use. “In Scotland, of the reported 867 drug-related deaths in 2016, 286 deaths were related to NPS use, and in most cases, benzodiazepine-type NPS were found to have been implicated in, or to have potentially contributed to, the cause of death.” Most cases found etizolam; there were a few related to diclazepam or phenazepam.

We mustn’t forget NPSs with opioid effects. “Between 2009 and 2017, a total of 34 synthetic opioids, including 26 fentanyl analogues, were reported to UNODC early warning advisory by countries on all continent.” Most of those were reported after 2016. The most frequently reported fentanyl analogues reported included: furanylfentanyl, acetylfentanyl, ocfentanil and butyrfentanyl.

Over the past few years kratom has gained popularity as a plant-based NPS in North America and Europe. Globally, 31 countries reported finding kratom between 2012 and 2017. The scientific literature links high doses of kratom with several adverse health events, including tachycardia, seizures and liver damage. “In North America in particular, a variety of products have been marketed as kratom, which may actually contain kratom in combination with other, often unknown, substances.” It was speculated the severe adverse health effects could be the result of the powdered, refined form of kratom instead of the traditional forms used in South-East Asia.

Currently, neither kratom nor the psychoactive substances contained in its leaves are under international control. Given the scarcity of data on the potential pharmacological, therapeutic and toxicological effects of kratom and kratom products, and the lack of controlled laboratory studies, it is difficult to understand the health risks and potential benefits associated with their use.

Concerns with NPSs are growing both locally and globally. I’ve been writing about problems related to them for almost four years now. NPSs have been linked to terrrorists (See “Strange Bedfellows: Terrorists and Drugs”). They are sold in some convenience stores, some tobacco or vape shops, as well as “head” shops selling water pipes and other paraphernalia (See “Gone Wild”). A stimulant-based NPS known as flakka had people stripping off their clothes and running naked through traffic a few years ago (See “Flack from Flakka”). It’s a problem among the poor and homeless (See “Weaponized Marijuana”). You can also read previous articles on this website by doing a search for “NPS”. Try: “The New Frontier of Synthetic Drugs”; “This Stuff Is Not Weed”; “Not Meant for Human Consumption”; or “Is Ketamine Really Safe & Non-Toxic?”