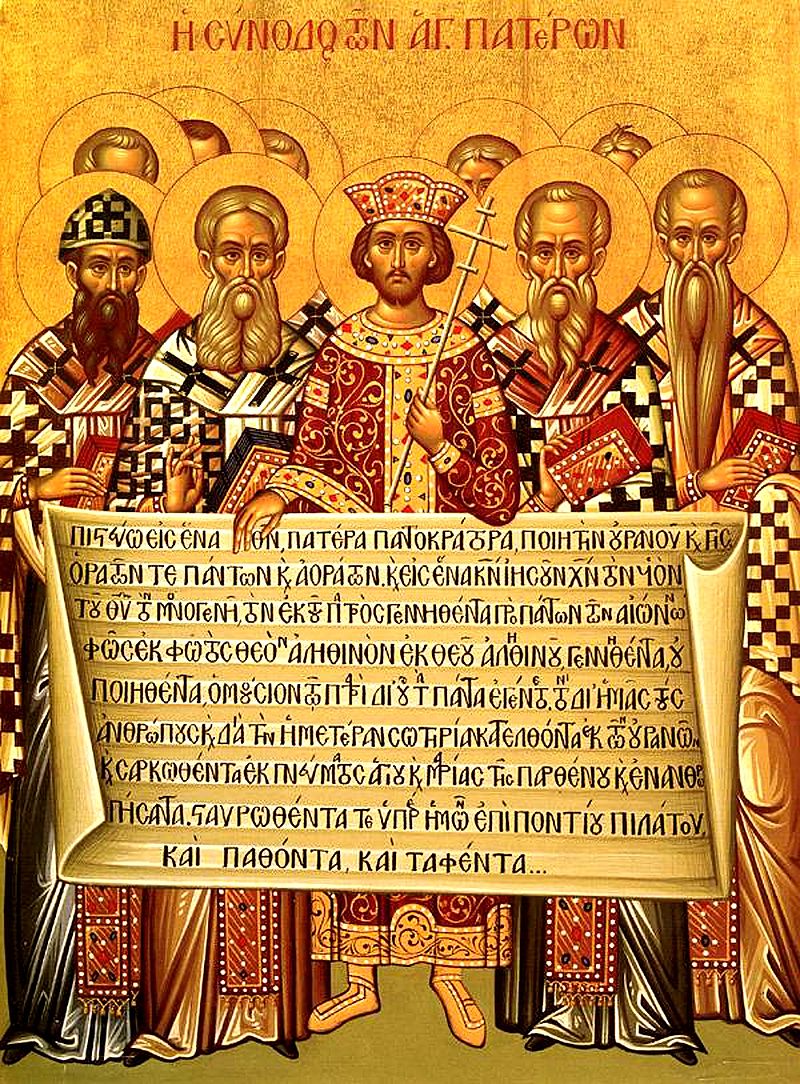

What we know today as the “Nicene Creed” or “C” was the most influential creedal product to come out of the fourth century. According to Graham Keith in “The Formulation of Creeds in the Early Church,” within a short period of time, it became essentially the only baptismal creed used in all the Eastern churches. And for a time, it was also the baptismal creed for Rome and the Western churches. But ironically, even though it bears the Nicene name, it was not formulated at the Council of Nicea in 325.

Sometimes it is technically called the “Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed,” referring to the Council of Constantinople in 381, which was when and where it was formulated. However some scholars have theorized the original text of “C” was actually formulated at the Council of Chalcedon seventy years later in 451, where it said: “At the third session of the Council, on 10 October, the Nicene Creed having been publicly read and acclaimed, the imperial commissioners ordered ‘the faith of the 150 fathers’ to be read out too.”

What was read then at Chalcedon was C. One fact in support of the claim that the Nicene Creed was originally formed at Chalcedon is the glaring silence or lack of reference to C between Council of Constantinople in 381 and the Council of Chalcedon in 451. In all the back-and-forth letter writing and synods and councils, there isn’t any reference to C as there was to “N”, the original creed of Nicea. What seems to be the right explanation for what happened is that the Council of Constantinople did formulate C, but the gathered church leaders did not consider their revisions as composing a new creed.

“The faith of Nicea” was applied at the time before Chalcedon when referring to creeds that were essentially Nicene, but whose wording was sometimes radically different than N. The intent of church leaders gathered at the Council of Constantinople was to confirm the teaching or faith of the Nicene Creed, which it did. The lack of separate references to C from 381 until near 451 may also be understood by the fact that the pristine text of N wasn’t distinguished from C until the Council of Ephesus in 431.

“The whole style of the creed, its graceful balance and smooth flow, convey the impression of a liturgical piece which has emerged naturally in the life and worship of the Christian community” (rather than as the product of an ecclesiastical committee). Therefore C was probably already in existence and use somewhere when the Council took it up, touched it up for their purposes, including “the special heresies it felt itself called upon to refute” and approved it as the Council’s affirmation of “the faith of Nicea.” J.N.D. Kelly speculated it was originally a local baptismal creed from the Antioch or Jerusalem family of creeds.

“Unlike the purely Western Apostles’ Creed, it was admitted as authoritative in the East and the West alike from 451 onward, and it has retained that position, with one significant variation in its text (the addition of the filioque clause), right down to the present day.” It became the baptismal creed of the East and the Eucharistic creed of all Christendom. In the following centuries, there was a growing emphasis on the basic identity of the two creeds, N and C.

|

Creed of Nicea “N” |

Constantinopolitan Creed “C” |

|

We believe in one God, the Father almighty, maker of all things visible and invisible; |

We believe in one God the Father almighty, maker of heaven and earth, of all things visible and invisible; |

|

And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, begotten from the Father, only-begotten, that is, from the substance of the Father, God from God, light from light, true God from true God, begotten not made, of one substance with the Father, through Whom all things came into being, things in heaven and things on earth, Who because of us men and because of our salvation came down and became incarnate, becoming man, suffered and rose again on the third day, ascended to the heavens, and will come to judge the living and the dead; |

And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only-begotten Son of God, begotten from the Father before all the ages, light from light, true God from true God, begotten not made, of one substance with the Father, through Whom all things came into existence, Who because of us men and because of our salvation came down from heaven, and was incarnate from the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary and became man, and was crucified for us under Pontius Pilate, and suffered and was buried, and rose again on the third day according to the Scriptures and ascended to heaven, and sits on the right hand of the Father, and will come again with glory to judge living and dead, of Whose kingdom there will be no end; |

|

And in the Holy Spirit. |

And in the Holy Spirit, the Lord and life-giver, Who proceeds from the Father [and the Son], Who with the Father and the Son is together worshipped and together glorified, Who spoke through the prophets; in one holy Catholic and apostolic Church. We confess one baptism to the remission of sins; we look forward to the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come. Amen. |

|

But as for those who say, There was when He was not, and, Before being born He was not, and that He came into existence out of nothing, or who assert that the Son of God is of a different hypostasis or substance, or is created, or is subject to alteration or change—these the Catholic Church anathematizes. |

|

When you compare the two creeds in the above chart, there are some notable omissions in C that are not easy to explain if C was a version of N. These differences are, a) “that is from the substance of the Father”; b) “God from God”; c) “things in heaven and things on earth”; and d) the anathemas. In the Creedal comparison chart, the phrases from N that were left out of C are in bold italic print. The additions to C not found in N are in bold print. The anathemas of Arianism in the original Creed of Nicea, “N,” were omitted in “C.” There are also various other differences like word order and sentence structure that make it difficult to say C is a modified version of N. So what’s going on here?

Several years before the Council of Constantinople, Basil the Great of Caesarea thought that a needed addition to the Nicene faith would be something elaborating on the Holy Spirit, because it only briefly mentioned Him. Apparently this was because He had not been the subject of any doctrinal disputes in the church by 325. The Arian controversy had kept questions about the status of the Holy Spirit in the background. But by the decade of the 350s, “His true nature and position began to be matters of public discussion.” So when the Council of Constantinople met in 381, one of the issues they intended to address was “To bring the Church’s teaching about the Holy Spirit in line with what was believed about the Son.”

“The Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed rebutted the heresies of the Pneumatomachi (who believed the Spirit was a created being; one of the ministering angels) as well as all Arians (who believed the Son/Word/Logos was not coeternal with the Father). It did this simply by affirming divine titles like ‘Lord’ which are used of the Spirit in Scripture, and it dealt with the difficult question of the Spirit’s mode of origin by declaring that ‘He proceeds from the Father’.” It also added the phrase, “whose kingdom shall have no end” at the end of the clause about Jesus Christ in order to counter Marcellus’ teaching. In the prefix to a letter accompanying the text of the “91 Canons of Constantinople,” which was sent to the Emperor Theodosius I, was the following. Theodosius I, who was the last emperor to rule over both the eastern and western halves of the Roman Empire, had summoned the council.

Having then assembled at Constantinople according to the letter of your Piety, we in the first place renewed our mutual regard for each other, and then pronounced some short definitions, ratifying the faith of the Nicene Fathers, and anathematizing the heresies which have sprung up contrary to it. In addition to this we have established certain canons for the right ordering of the Churches, all of which we have subjoined to this our letter. We pray therefore your Clemency, that the decree may be confirmed by the letter of your Piety, that as you have honoured the Church by the letters calling us together, so also you may ratify the conclusion of what has been decreed. That the faith of the 318 Fathers [the original Nicene Creed of 325] who assembled at Nicaea in Bithynia, is not to be made void, but shall continue established; and that every heresy shall be anathematized, and especially that of the Eunomians or Anomoeans, and that of the Arians or Eudoxians, and that of the Semiarians or Pneumatomachi, and that of the Sabellians and Marcellians, and that of the Photinians, and that of the Apollinarians.

The addition of the filioque clause (and from the Son) was favored by Hilary, Ambrose, Jerome and Augustine (354-430). It was first inserted into C by the Council of Toledo in 589. It became part of the creedal pattern in the Western churches and a matter of contention between the West and the East that persists to the present day. Augustine saw the Trinity as one simple Godhead, who in its essence was Trinity. “The logical development of his thought was that ‘the Holy Spirit proceeded as truly from the Son as from the Father.’” This way of thinking about the Trinity became universally accepted in the West in the 5th and 6th centuries. So the addition of the phrase “and the Son” (filioque) became known as the doctrine of the double procession, the Holy Spirit proceeding from the Father and the Son. Starting in the sixth century, C was the declaratory creed used in the Roman baptismal rite until the Apostles’ Creed was adopted several centuries later.

In contrast, the Eastern understanding followed Gregory of Nyssa, who said one of the Persons of the Trinity stood as cause to the other two. Therefore, the Eastern churches would say the Spirit proceeded from the Father through the Son, who was the Father’s instrument or agent. Philip Schaff, in The Creeds of Christendom said the Greek Church remains as much opposed to the filioque clause today as ever, considering it to be an “unauthorized, heretical, and mischievous innovation.” He noted where the Eastern Patriarchs and other prelates gave no less than fifteen arguments against the filioque in their 1848 reply to “The Epistle of Pius IX.”

Information on the creeds and heresies discussed here was taken primarily from Early Christian Creeds and Early Christian Doctrines by J. N. D. Kelly; A History of Heresy by David Christie-Murray; and The Canon of the New Testament by Bruce Metzger. For more on the early creeds and heresies of the Christian church, see the link: “Early Creeds.”