There is a growing call to permit research into the therapeutic benefits of a variety of psychoactive drugs currently classified by the DEA as Schedule 1 controlled substances. The editors of Scientific American called for the U.S. government to move LSD, ecstasy, marijuana and others into Schedule 2, with cocaine, methamphetamine, fentanyl and Ritalin. They point out that such a move would not lead to decriminalization, “but it would make it much easier for clinical researchers to study their effects.”

Schedule 1 controlled substances are “drugs with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.” They are seen as the most dangerous drugs, “with potentially severe psychological or physical dependence.” Schedule 2 controlled substances are “drugs with a high potential for abuse, less abuse potential than Schedule 1 drugs, with use potentially leading to severe psychological or physical dependence.”

British researchers have also called for greater access to “classical hallucinogens” such as psilocybin (magic mushrooms, another Schedule 1 drug) and LSD for research into treating depression.

Classical hallucinogens alter the functioning of this system [serotonergic], but not in the same way current medications do: whilst there are identified receptors and neurotransmitter pathways through which hallucinogens could therein produce therapeutic effects, the neurobiology of this remains speculative at this time.

These drugs are all caught in a catch-22, de facto ban on their use in medical research because of their Schedule 1 placement. “These drugs are banned because they have no accepted medical use, but researchers cannot explore their therapeutic potential because they are banned.” Three United Nations treaties extend similar prohibitions to rest of the globe, further complicating their reclassification as Schedule 2 drugs.

British psychiatrist David Nutt has argued that the U.N. charters are outdated and restrict doctors and scientists from studying hundreds of drugs. He likened this “research censorship” to the Catholic Church banning Galileo from teaching or defending heliocentric ideas in the 1600s. Nutt suggested the Catholic Church banned the telescope, but the ban was actually on books that taught Copernican beliefs.

Nevertheless, he called the laws, which do not discriminate between research and recreational drug use relics of another age. “These laws serve no safety value. . . . The licenses and bureaucracy surrounding them can increase the costs of research tenfold, further limiting what is done.” Dr. Nutt commented on how LSD and other hallucinogens like psilocybin had potential to explore and treat the brain. “Other therapeutic targets for psychedelics are cluster headaches, OCD and addiction.”

The argument for reclassifying psychoactive substances like marijuana, LSD, ecstasy and psilocybin from Schedule 1 to Schedule 2 has its pros and cons for me. The above discussion presents the case for reclassification, permitting future research into these substances. IF the ideal of rigorous, methodical research into the therapeutic potential of these drugs is followed, all is well.

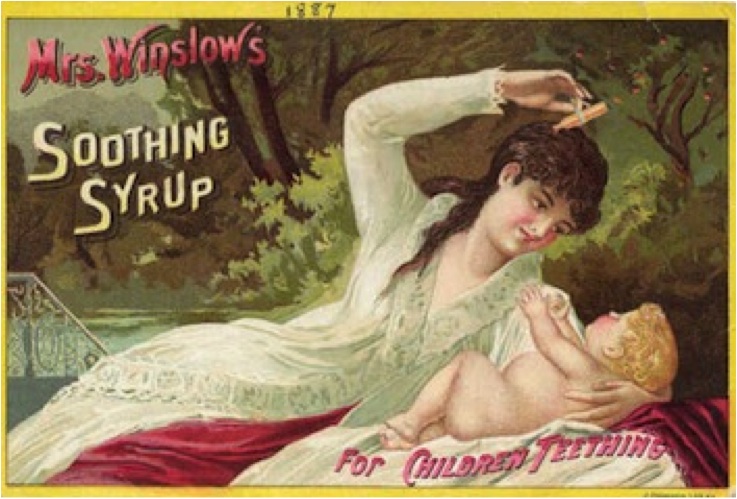

But we are now in the midst of an epidemic of prescription drug abuse that came through the very same gauntlet of review and approval that these known recreational drugs would pass through to become medicinal agents once they were reclassified. And while there are potential therapeutic applications for marijuana, the current state of medical marijuana looks more like the older sideshow of patent medicines, where you could get cocaine toothache drops, heroin for cough relief, and Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup (which contained morphine) for teething discomfort.

If special interest groups can be held off from bringing about a new age of snake oil salesmanship, then reclassifying these substances and permitting legitimate scientific research makes sense. Done correctly, it might even demonstrate that some of the existing curative claims for medical marijuana and other substances were false. But if these psychoactive substancess achieve FDA approval for any reason, they could be prescribed “off label” as is currently the case with other FDA approved drugs.

If special interest groups can be held off from bringing about a new age of snake oil salesmanship, then reclassifying these substances and permitting legitimate scientific research makes sense. Done correctly, it might even demonstrate that some of the existing curative claims for medical marijuana and other substances were false. But if these psychoactive substancess achieve FDA approval for any reason, they could be prescribed “off label” as is currently the case with other FDA approved drugs.