The Not-So-Golden Years

Dr. Stephen Barnes wrote a thoughtful article on the so-called golden years of adulthood. In case you’re wondering when (or if) you reach said span of time, he said it begins with retirement and ends with the beginning of “age-imposed physical, emotional, and cognitive limitations; roughly between the ages of 65 and 80+. This can be a time of self-fulfillment, with many positive outcomes related to aging. Of course there are some variables to consider: do you have good physical and psychological health; do you have adequate financial resources; do you now have fewer family and career responsibilities. If you do, then there are opportunities for “self-fulfillment, purposeful engagement, and completion.” However, there is another perspective on the golden years for us to consider—that of Dr Seuss:

The Golden Years have come at last.

I cannot see.

I cannot pee.

I cannot chew.

I cannot screw.

My memory shrinks.

My hearing stinks.

No sense of smell.

I look like hell.

My body is drooping.

I have trouble pooping.

The Golden Years have come at last.

The Golden Years … can kiss my ass.

There was a study done by Gray et al. published in JAMA Internal Medicine for March of 2015 that caught some media attention. It looked at the cumulative use of anticholinergics and dementia. This class of drugs blocks a neurotransmitter called acetylcholine (ACh), which is found throughout the body. Dr. Sandra Steingard noted: “It is involved in gut motility, visual acuity, heart rate, and secretions. In the brain, its activity is linked to memory and movements.” There are a wide variety of drugs with an anticholinergic effect, from antihistamines like Chlor-Trimeton, Unisom (diphenhydramine), Vistaril and Benedryl to antidepressants like Paxil, antipsychotics like Seroquel and Zyprexa, and even Detrol (oxybutinin).

Anticholinergics often cause dry mouth, constipation, rapid pulse, urinary retention, blurred vision and impaired memory. Notice how they correspond to four of Seuss’ complaints. Dr. Steingard also commented on the Gray et al. study and said there were two major findings of the study. “The first is that total exposure to anticholinergic drugs increases the risk of developing dementia. But of further concern, these effects were seen even if the drugs had been stopped years before the onset of dementia.” The study found a dose response risk for developing dementia—a greater exposure to anticholinergics meant a greater risk.

Steingard thought the study was carefully done. Her one complaint was it didn’t have a very complete list of anticholinergic drugs. She provided a link to a chart from AgingBrainCare.org with a more complete listing. As a psychiatrist, she thought the study had particular implications for psychiatry since many psychiatric drugs have anticholinergic effects. Several antipsychotics were in the most severe category.

Many people are now being exposed to psychiatric drugs at very young ages, and are taking them for many years. “We need to use these drugs with caution. Dose matters. Length of time a person is on them matters. Polypharmacy matters.”

The Gray et al. study concluded that there was an increased risk for dementia in people with higher use of anticholinergics. The findings suggested that someone taking even one such drug for more than three years “would have a greater risk for dementia.”

Prescribers should be aware of this potential association when considering anticholinergics for their older patients and should consider alternatives when possible. For conditions with no therapeutic alternatives, prescribers should use the lowest effective dose and discontinue therapy if ineffective. These findings also have public health implications for the education of older adults about potential safety risks because some anticholinergics are available as over-the-counter products. Given the devastating consequences of dementia, informing older adults about this potentially modifiable risk would allow them to choose alternative products and collaborate with their health care professionals to minimize overall anticholinergic use.

Another area of concern within the so-called golden years is substance abuse. Ironically, the initial step into the golden years via retirement is seen as a contributing factor into senior substance abuse. Paul Gaita, writing for The Fix, indicated several aspects of retirement could lead to greater drug and alcohol use among seniors. The circumstances leading to retirement as well as the economic and social nature of retirement are two possible features. A substance abuse counselor added: “In retirement, there can be depression, divorce, death of a spouse, moving from a big residence into a small residence.”

There are issues of loneliness, anxiety and boredom to consider. Then there is the reality of the increased likelihood of medical issues and the death of family or friends who are older. And don’t forget changes in body metabolism. The liver slows down as does kidney filtration. Both of these factors lead to alcohol and drugs staying active in the body for longer periods of time. Then there are medical issues like menopause, limited mobility, sleeping problems and chronic pain.

SAMHSA publishes a free volume in its Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series entitled: “Substance Abuse Among Older Adults” (TIP 26). It contains chapters on alcohol use and abuse, prescription and over-the-counter drug use and abuse, referral and treatment approaches, as well as appendixes of assessment tools. Here I will highlight the Executive Summary and chapter 1, “Substance Abuse Among Older Adults: An Invisible Epidemic.”

TIP 26 also noted that physiological change and changes in kinds of responsibilities and activities pursued are factors in substance abuse with older adults. Individuals 65 and over consume more prescribed and over-the-counter medications than any other age group in the U.S. Concerns with benzodiazepine use and sleep aides were noted. Limited use of both drug classes was given. Antihistimines and anticholinergics were highlighted as well.

Older persons appear to be more susceptible to adverse anticholinergic effects from antihistamines and are at increased risk for orthostatic hypotension and central nervous system depression or confusion. In addition, antihistamines and alcohol potentiate one another, further exacerbating the above conditions as well as any problems with balance. Because tolerance also develops within days or weeks, the Panel recommends that older persons who live alone do not take antihistamines.

Substance misuse among adults 60 an older is one of the fastest growing health problems in the country. Yet the situations is underestimated, underidentified and undertreated. “Until relatively recently, alcohol and prescription drug misuse, which affects up to 17 percent of older adults, was not discussed in either the substance abuse or the gerontological literature.” Diagnosis or identification can be difficult because symptoms of substance abuse in older adults will sometimes mimic symptoms of other medical and behavioral concerns such as diabetes, dementia and depression. Adding to this issue is that drug trials of new medications rarely include older adults. So even recognizing the presence of adverse drug reactions with older adults often doesn’t happen until enough adverse events accumulate after the drugs have been approved.

Alcohol abuse can accelerate the normal decline of physiological functioning that happens with aging. There is also the probability of an increased risk of injury, illness and socioeconomic decline. Increased benzodiazepine use with older adults also causes problems. The BMJ indicated that the mass of evidence suggested the benefits of benzodiazepines in older adults rarely outweigh their risks.

Benzodiazepine risks, whether short-term or chronic, include cognitive impairment, delirium, respiratory insufficiency, falls, fall-related injuries such as hip fractures, motor vehicle crashes, and death. Most patients are not warned of these risks before starting these medications. The main risk factor for chronic benzodiazepine use is any previous use, so an intended short-duration prescription of these habit-forming medication is likely to lead to their long-term use. Chronic benzodiazepine users are rarely prompted to discontinue, despite good evidence for the safety and tolerability of tapering protocols.

Ageism also contributes to the problem. “There is an unspoken but pervasive assumption that it’s not worth treating older adults for substance use disorders.” Behaviors that are seen as problematic in younger adults may not inspire the same urgency for treatment with older adults. Also, there can be an attitude that treatment for this population is a waste of health care resources. Attitudes like these are callous and based on misperceptions. For example, most older adults live independently. Only 4.6% of adults over 65 are in nursing homes or personal care facilities.

The reality is that misuse and abuse of alcohol and other drugs take a greater toll on affected older adults than on younger adults. In addition to the psychosocial issues that are unique to older adults, aging also ushers in biomedical changes that influence the effects that alcohol and drugs have on the body.

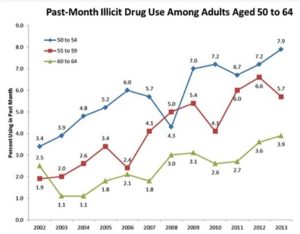

Health care and social service providers working with older Americans will mainly encounter abuse or misuse of alcohol or prescribed drugs. Although a smaller population, illicit drug users over 60 are increasing. This trend is at least partly due to aging baby boomer whose rates of illicit drug use have historically been higher than previous generations. The following chart from a NIDA report tracks past month use of illicit drugs among adults aged 50 to 64.

Here is a more intimate and personal look at this issue. Patrick O’Neil, described coping with his 79 year-old mother’s recovery from hip surgery in “I Can’t Watch My Mom Detox.” Incidently, her HMO had been heavily prescribing Vicodin for seven years. Before the surgery. The medical team is considering detoxing her from her dependency on hydrocordone WHILE she’s recuperating from her hip surgery “for her own good.”

A doctor I’ve never met takes me aside and explains the process, how the patient will appear to be suffering but it’s for her own good.

I look at her skeptically. “So you’re going to detox my mom in the middle of her recovering from one of her most painful surgeries ever, because you’re having a knee-jerk reaction to your HMO being at fault for keeping her addicted?”

“It’s a little more complicated than that,” replies the doctor.

“Well, try and explain it then,” I say. “Because it looks exactly like that to me.”

O’Neil is himself a recovering heroin addict and author of his own journey through addiction in Gun, Needle, Spoon. So he really understands what his mother is going through. He suggests they not attempt a detox until after she’s healed from her surgery. It seems they finally agreed.

When I was growing up, my mom never had an obvious substance abuse problem. Even though her father was an alcoholic and addiction is thought to be hereditary, she never exhibited any outright addictive behaviors. And until recently, she hadn’t displayed the sort of desire to overmedicate that I had. Only with age, her retiring, my stepfather dying and close friends passing, she’d lost interest in life. These days she sits at home, alone. Her health, having never been great, is deteriorating even more. When her knee went out, she had it replaced and the doctor prescribed Vicodin. And suddenly, the same monster that lives in me was awakened in my mom and she took to them like they were the solution to all her problems.

“The Golden Years have come at last. The Golden Years … can kiss my ass.”