Dimming the Experience of Pleasure and Addiction

Neuroscience News reported on a recent study led by researchers from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and other federal agencies that found the brain’s ‘salience network’ was only activated when drugs were taken intravenously or smoked, but not ingested orally. “When drugs enter the brain quickly, such as through injection or smoking, they are more addictive than when they enter the brain more slowly, such as when they are taken orally.” The study suggests there’s new information on what may be behind the difference.

Nora Volkow, senior author of the study said, “We’ve known for a long time that the faster a drug enters the brain, the more addictive it is – but we haven’t known exactly why.” Using new imaging technology, the researchers believe they may now have an understanding of why this is. “Understanding the brain mechanisms that underlie addiction is crucial for informing prevention interventions, developing new therapies for substance use disorders, and addressing the overdose crisis.”

The researchers conducted a double-blind, randomized, counterbalanced clinical trial that used simultaneous PET/fMRI imaging. There were twenty adults who participated in the trial. Over three separate sessions, they received either a small dose of placebo or methylphenidate (Ritalin), orally or intravenously. After the participants received the study drug or placebo, the researchers looked at the differences in dopamine levels (through PET imaging) and brain activity (through fMRI imaging). The participants also reported their subjective experience of euphoria in response to the drug.

Consistent with previous research, the PET scan showed when participants received the methylphenidate orally, their dopamine rate peaked more than an hour after administration. However, participants who received methylphenidate intravenously, peaked within 5 to 10 minutes of administration. The fMRI of the participants indicated the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (where we process risk and fear) was less active after both oral and intravenous drug use. “However, two brain regions, the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex [associated with learning and self-control] and the insula [linked with salience detection and addiction], which are part of the brain’s salience network, were activated only after receiving the injection of methylphenidate, the more addictive route of drug administration.” The same areas of the brain were not activated after taking methylphenidate orally.

The salience network of the brain attributes value to things in our environment. It is important for recognizing and translating internal bodily sensations, like the euphoric effects of drugs. “This research adds to a growing body of evidence documenting the important role that the salience network appears to play in substance use and addiction.” Interestingly, other studies have shown when people experience damage to their insula (part of the brain’s salience network), they may have a complete remission of their addiction.

After receiving the drug intravenously, researchers noticed that the activity and connectivity of the salience network, observed via fMRI imaging, very closely paralleled almost every participant’s subjective experience of feeling high. When the imaging showed increased activity in this part of the brain, participants’ reports of feeling high increased.

When the imaging showed decreasing activity in the salience network, participants’ reports of feeling high decreased. Researchers theorize that the network identified in this study is relevant not just for the chemical action of the drug, but also the conscious experience of drug reward.

The authors indicated a next step would be to see whether inhibiting the salience network when someone takes a drug effectively blocks the feeling of being high. This would further support the salience network as a target for the treatment of substance use disorders. The lead author of the study said, “I’ve been doing imaging research for over a decade now, and I have never seen such consistent and clear fMRI results across all participants in one of our studies.”

Manza et al, the study reported in Neuroscience and discussed above, said: “Together, these findings provide insight into how the salience network is critically linked to the pathophysiology of substance use disorder.” Among the considerations to note in the study, participants were naïve to stimulant drugs. The participants were also administered methylphenidate in a laboratory environment, which tends to inhibit the results. For example, other studies have shown adult males will drink significantly more alcohol when they are exposed to a simulated bar environment relative to a neutral laboratory setting. Manza et al further said:

Notably, our study identified two distinct circuits similar to the pattern of brain lesions leading to clinical remission of addiction. Patients who suffered stroke lesions to brain regions that had positive functional connectivity with dACC [dorsal anterior cinugulate] and insula (where we observed activation with fast dopamine increases), and lesions to brain regions that had negative functional connectivity with ventromedial prefrontal cortex (where we observed deactivation both with slow and fast dopamine increases) led to remission. Therefore, both studies support interventions to inhibit the dACC and insula and interventions to stimulate the ventromedial prefrontal cortex as strategies for the treatment of substance use disorder. Indeed, the dACC is being tested as a neuromodulation target to combat compulsive drug use with preliminary findings showing decreases in cocaine self-administration, cue-induced alcohol craving, and heavy drinking days. Critically, in the latter study, successful stimulation effects were associated with decreased connectivity between dACC and caudate. A key next step is to evaluate if inhibition of this circuit during drug administration blocks the subjective experience of drug reward, which could open new avenues to treat substance use disorders.

The Reward Pathway and Addiction

The significance of the above-described study demonstrating the importance of fast or slow dopamine increases in the develop of a substance use disorder can be understood by reviewing Carleton Erickson’s description of the Reward Pathway of the brain in his book, The Science of Addiction. Erickson capitalizes the word “Addiction” to represent when addiction progresses to the stage of physical dependence.

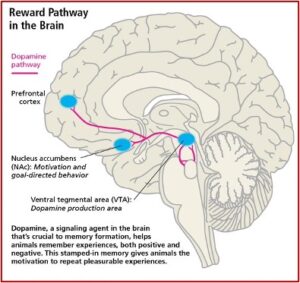

Drugs produce “Addiction” in the mesolimbic dopamine system (MDS), the pleasure pathway located in the middle of the brain. It is believed that addiction problems develop when the function of these MDS neurotransmitter systems are disrupted due to genetic problems, long-term exposure to a drug, or a combination of these with environmental influences. The MDS generates signals in the part of the brain known as the ventral tegmental area (VTA), which releases dopamine (DA) into the nucleus accumbens (NAc). This release of DA into the NAc causes the feelings of pleasure, but not only from drugs. Other areas of the brain, like the basal ganglia, create a lasting record or memory that associates the good feelings with the from the drug use with the circumstances and environment in which they occur. See the figure below.

Release of DA in the NAc produces the sensation of pleasure. The anticipation of obtaining the drugs activates the limbic pathways in a way that leads to chemical dependence, to Addiction. This is why the above discussed study is significant and as the researchers speculated, opens “new avenues to treat substance use disorders.” But there is a potential problem with inhibiting connectivity between the dACC and insula in the treatment of substance use disorder as suggested.

In Never Enough, the neuroscientist Judith Grisel explained when activity in the mesolimbic pathway is prevented, the person is unable to experience pleasure. If activity in the mesolimbic pathway was prevented before a person used drugs, she said they’d “think the drugs were a complete waste of money.”

This might look like a cure, but … it is ethically problematic. Such an intervention would prevent pleasure from all sources, including things like food and sex. Most of the world has prohibited this sort of surgical intervention, although some nations, including China and the Soviet Union, are reportedly reducing relapse rates by employing this strategy. However, it doesn’t work all that well for seasoned addicts who use mainly to avoid unpleasant symptoms associated with withdrawal rather than seeking a high.

Addicts who are clearly suffering from their addiction are generally not willing to voluntarily undergo a procedure that would produce this form of anhedonia, a global deficit in their experience of pleasure. Most would rather go to prison or suffer other severe consequences, because then they could still experience transient pleasures. “Without dopamine in the nucleus accumbens, nothing, a letter from a friend, an especially beautiful sunset or piece of music, or even chocolate, would alleviate a persistently bleak existence.”

The research of Manza et al, reported by Neuroscience and discussed above is interesting. And when it’s replicated, it will become even more important to our growing knowledge of addiction. I would hope as we pursue the association of dopamine and addiction, that future research won’t dim the person’s experience of pleasure as it tries to cure their addiction.