Antipsychotic Big Bang

Duff Wilson wrote in “Side Effects May Include Lawsuits” that antipsychotics were a niche product for decades. Yet they have recently generated sales that have surpassed that of “blockbusters like heart-protective statins.” In the 1990s, pharmaceutical companies began marketing them for much broader uses than the original FDA approved uses for more serious mental illnesses, like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. A Scientific American article reported that pediatric prescriptions for atypical antipsychotics rose 65%—from 2.9 million to 4.8 million—between 2002 and 2009. And a New York Times article noted that federal investigators have found widespread overuse of psychiatric drugs by older Americans with Alzheimer’s disease.

There are two more facts to introduce you to about neuroleptics or atypical antipsychotics. First, in 2008, antipsychotics sales reached $14.6 billion, making them the biggest selling therapeutic class of drugs in the U.S. Second, each of the following pharmaceutical companies that marketed antipsychotics has been investigated for misleading marketing under the False claims Act. All their neuroleptics—Risperdal (risperidone; Johnson & Johnson), Zyprexa (olanzapine; Eli Lilly), Seroquel (quetiapine; AstraZeneca), Geodon (ziprasidone; Pfizer), and Abilify (aripiprazole; Bristol-Myers Squibb and Otsuka)—are now off patent.

The primary use off-label use of neuroleptics for the elderly and with children has been for behavioral control. A recent study commissioned by the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services found that children between the ages of 6 and 18 who were in foster care was four times higher than other youth in Medicaid. More than half of these youth had a diagnosis of ADHD. “This is concerning, as the majority of these youth did not have another diagnosis that clinically indicated the use of antipsychotics.” Risperidone was the most frequently prescribed antipsychotic medication among the youth. However, Abilify and Seroquel grew to exceed risperodone over the course of the study. Zyprexa was the least commonly used antipsychotic among all youth.

A trade group for nursing homes, The American Health Care Association, indicated that while antipsychotics helped some dementia patients who have hallucinations or delusions, “They also increase the risk of death, falls with fractures, hospitalizations and other complications.” The American Psychiatric Association, among others pointed to a JAMA Psychiatry study that showed mortality risks increased in patients given antipsychotics to reduce their symptoms of dementia. Another study published in Health Policy said the benefits and harms of using antipsychotic medications in nursing homes should be reviewed.

Antipsychotic medication use in nursing home residents was found to have variable efficacy when used off-label with an increased risk of many adverse events, including mortality, hip fractures, thrombotic events, cardiovascular events and hospitalizations.

Another “add on” area for neuroleptic use is when it is used with an antidepressant for “treatment resistant” depression. On BuzzFeed, Cat Ferguson reported how the sale of antipsychotics such as Abilify, and Zyprexa “skyrocketed” as they were approved to treat depression as an add-on medication. Seroquel is not FDA approved to treat major depression, but along with Abilify and Zyprexa is approved to treat bipolar depression in adults. Zyprexa and Seroquel are approved for some indications of bipolar disorder in adolsecents, but Abilify is only used off label with bipolar children, having “low or very low evidence of efficacy.” See the Psychopharmacology Institute for more information on these drugs and their approved and off-label uses.

Ferguson quoted a few psychiatrists expressing concern about the antipsychotic boom, and there are some surprises given other stands they’ve taken. Allen Frances, the former chair for the DSM-IV, agreed there has been heavy marketing of antipsychotics. He thought they are prescribed too quickly for depression and without clear indication of their efficacy. He added there seemed to be pressure from the pharmaceutical companies. He said: “These drugs should have a narrow indication, and instead they’ve become the highest revenue-producing drugs in America.”

Over the past few years Allen Frances has become an outspoken critic of some psychiatric practices, including the overuse of antipsychotics and antidepressants. He’s also been critical of the DSM-5. He’s even written Saving Normal to address his concerns with psychiatry and psychiatric practice. Search for his name here to find several articles where he is mentioned.

I was surprised and encouraged to see Jeffrey Lieberman, the chair of psychiatry at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons express concern with the over prescribing of antipsychotics. Lieberman has positioned himself as defender of psychiatry and psychiatric practice, recently publishing Shrinks. You can also search his name here to see other articles interacting with his book and position on psychiatry. Lieberman said that antipsychotic medication should be used sparingly in treating nonpsychotic disorder, including depression. He said: “I think there’s the possibility that antipsychotics are overprescribed, not just for depression, but in other areas.”

My point is that when two prominent psychiatrists with opposing views on many areas of psychiatry and psychiatric practice agree that antipsychotics are overused, pay attention. Both Frances and Lieberman have pointed out elsewhere how pharmaceutical marketing strategies contribute to this problem, but some pharma companies and representatives put the blame back on doctors. An Eli Lilly spokesperson said pharmaceutical companies aren’t responsible for how their drugs are used by doctors. “Physicians make prescribing decisions, not pharmaceutical companies. . . . While certainly we inform doctors of the benefits and risks of our medicine, it’s really up to physicians to prescribe the right medicine.”

But this attempt to deflect responsibility onto physicians is a cop out when you consider the marketing done by pharmaceutical companies for their products. In this YouTube advertisement for Abilify as an antidepressant add-on, you see how Bristol-Myers Squibb actively encouraged individuals to “ask your doctor if Abilify is right for you.” Pay attention to the fact that the first thirty seconds verbally describes how Abilify can help, while the rest of the 90-second commercial has the woman and her family going on a picnic while the adverse side effects are described.

Another problem is that all clinical trials for drug approval are done over short periods of time—six or eight weeks—antipsychotics included. But what are the long-term consequences of antipsychotics? As Dan Iosifescu, the director of the Mood and Anxiety Disorders Program at Ichan School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital said, “It’s just a fallacy to take short-term data and extrapolate it for long term.” His bottom line is that antipsychotics tend to be helpful in the short term, but can have major consequences in the long term.

Thomas Glasen, writing in Schizophrenic Bulletin, weighed the pros and cons of medication treatment for psychosis. In the case for medication, he noted that the benefits of medication were profound. The therapeutic power of antipsychotic medication had been validated in countless studies and was now the primary treatment of schizophrenia. “In today’s climate, treating schizophrenia without medication mobilizes high anxiety among treaters for the safety of their patients from irrationality and for the safety of themselves from litigation.” However, in the case against medication, Glasen said:

Antipsychotics obscure the pathophysiology of psychosis by altering the neurobiology of the brain and the natural history of [the] disorder. . . . Medication can be lifesaving in a crisis, but it may render the patient more psychosis-prone should it be stopped and more deficit-ridden should it be maintained.

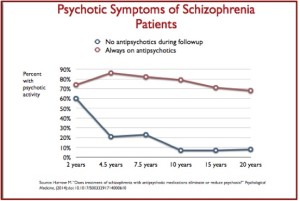

So how do individuals on long-term antipsychotics do? In Anatomy of an Epidemic, Robert Whitaker described Martin Harrow’s presentation of a long-term study funded by NIMH on sixty-four individuals diagnosed as schizophrenic between 1975 and 1983. Whitaker had just reviewed a series of studies questioning whether there was a long-term benefit to the use of antidepressants before discussing the Harrow study. He then said: “If the conventional wisdom is to be believed, then those who stayed on antipsychotics should have had better outcomes.” Harrow found that after two years, there was evidence that the off-med group was doing slightly better than the group on drugs.

Then, over the next thirty months, the collective fates of the two groups began to dramatically diverge. The off-med group began to improve significantly, and by the end of 4.5 years, 39 percent were “in recovery” and more than 60 percent working.

The outcomes for the medication group worsened and this divergence continued. At the fifteen-year follow up, 40 percent of those off drugs were in recovery and more than half were working; only 28 percent suffered from psychotic symptoms. “In contrast, only 5 percent of those taking antipsychotics were in recovery, and 64 percent were actively psychotic.” The 2007 Harrow study can be found here. Harrow said that not only was there a significant difference in global functioning between the two groups, 19 of the 23 (83%) schizophrenic patients with uniformly poor outcome after fifteen years were on antipsychotics.

Harrow et al. (2014) continued his study and reported data in Psychological Medicine at the twenty-year stage of his follow-up schedule. Here he investigated whether multi-year treatment with antipsychotics reduced or eliminated psychosis; and whether the results were superior to individuals in the non-medicated group. The data showed that the pattern noted above by Whitaker in Harrow’s 2007 report continued: “A surprisingly high percentage of SZ prescribed antipsychotic medications experienced either mild or more severe psychotic activity.” The figure to the left, originally from the 2014 Harrow et al. report, shows that 68% of the medication group experienced psychotic activity, while only 8% of the off-med group experienced any psychotic activity. The source of the figure was a slide reproducing the Harrow data in a presentation by Robert Whitaker at the “More Harm than Good” conference sponsored by the Council for Evidence-Based Psychiatry (CEP). The slides and videos of the presentation can be found here.

Harrow et al. (2014) continued his study and reported data in Psychological Medicine at the twenty-year stage of his follow-up schedule. Here he investigated whether multi-year treatment with antipsychotics reduced or eliminated psychosis; and whether the results were superior to individuals in the non-medicated group. The data showed that the pattern noted above by Whitaker in Harrow’s 2007 report continued: “A surprisingly high percentage of SZ prescribed antipsychotic medications experienced either mild or more severe psychotic activity.” The figure to the left, originally from the 2014 Harrow et al. report, shows that 68% of the medication group experienced psychotic activity, while only 8% of the off-med group experienced any psychotic activity. The source of the figure was a slide reproducing the Harrow data in a presentation by Robert Whitaker at the “More Harm than Good” conference sponsored by the Council for Evidence-Based Psychiatry (CEP). The slides and videos of the presentation can be found here.

Harrow et al. thought the high percentage of the medication group experiencing psychotic activity was influenced by two factors. One was the high vulnerability to psychosis of many schizophrenic patients, leading to a high risk of psychosis. But that begs the question of how the medication group in the study had such a high number of patients “at risk of psychosis.” Given the above data, their second factor seems to have been the more important factor: prolonged use of antipsychotics (or partial dopamine blockers) may produce a medication-generated build-up of supersensitive dopamine receptors or excess dopamine receptors.

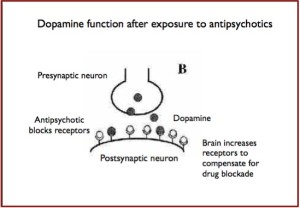

The production of excess or supersensitive dopamine receptors would then be an iatrogenic, drug induced effect from the long-term use of antipsychotics. The brain increases or sensitizes the receptors, thus compensating for the blockade of original receptors in the postsynaptic neuron. Again, drawing from Whitaker’s presentation slides at the CEP conference, it would look like this:

The above presentation of Harrow’s data and the discussion from Whitaker’s CEP presentation seem to affirm Glasen’s thesis that antipsychotics could alter the neurobiology of the brain. Antipsychotics reduce the activity of dopamine systems, stimulating the increase of receptors. When the antipsychotic is tapered or withdrawn, this would not immediately diminish the number of additional dopamine receptors produced by the brain to compensate for the dopamine blocking action of the antidepressant. With decreased antipsychotic levels, the result would be increased activation of the postsynaptic neurons because of the greater number receptors to absorb dopamine.

The person’s symptoms could intensify through the increased absorption of dopamine because of this disregulation of the dopamine system. In other words, tapering off of antipsychotics could activate symptoms like mania, paranoia and hallucinations because of the chemical imbalance produced by the medication. The experience of mania from a too sudden withdrawal of an antipsychotic is in this view, likely a withdrawal or discontinuation symptom instead of proof that the person needs to remain on an antipsychotic because they have a chemical imbalance. Robert Whitaker’s conclusion in Anatomy of an Epidemic was:

What the scientific literature reveals is that once a person is on an antipsychotic, it can be very difficult and risky to withdraw from the medication, and that many people suffer severe relapses. But the literature also reveals that there are people who can successfully withdraw from the medications and that it is this group that fares best in the long term.