Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out

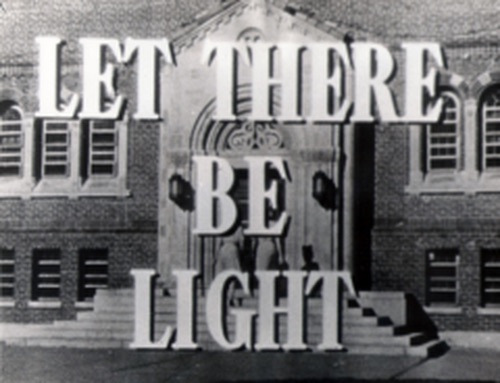

At the end of the Second World War in 1946 the Army wanted to show how new “experimental” treatments at the time, hypnosis and injections of sodium pentothal, were helping psychiatric casualties of war. These cases of “battle neurosis,” what we now call PTSD, were highlighted in a documentary called “Let There Be Light.” John Houston spent two months filming the documentary at Mason General Hospital. We see a paralyzed man (with no physical injury to explain it) walk; a soldier with amnesia regained his memories; and a man with a severe stutter cured. Then the Army prohibited Houston from releasing the film; it wasn’t until 1980 that it was released to the public.

Houston thought the reason it was sidelined was the film contradicted how the government portrayed the returning soldier. The film opened with this quote: “About 20% of all battle casualties in the American Army during World War II were of a neuropsychiatric nature.” In his autobiography he said: “I think it boils down to the fact that they wanted to maintain the ‘warrior’ myth, which said that our Americans went to war and came back all the stronger for the experience, standing tall and proud for having served their country well.” The official, flimsy, reason given was it was a violation of the soldiers’ privacy. Yet “the soldiers themselves were knowingly and consensually filmed.” It seems that Houston was too realistic.

None of the scenes were staged. “The cameras merely recorded what took place in an Army Hospital.” Writing for ZeroHedge, Tyler Durden said although the film intended to optimistically show the new treatments unavailable to soldiers of previous wars, but the audience takeaways were not positive. Instead of showing the potential for healing, audiences remembered “the psychosomatically paralyzed soldier being carried into a room, the trembling amnesiac, and the incommunicable stuttering of a psychologically damaged man.”

The soldier’s joy at the successful treatment did not explain, for audiences unfamiliar with such psychological phenomena, how such a problem could manifest. In all three cases of treatment, Huston believed he was showing the world the tremendous breakthroughs of psychiatric medicine, but instead, he showcased the horrors of war, without even having to visit a battlefield.

“Battle neurosis” was known as “shell shock” in World War I. Within the first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) it was “gross stress reaction,” which would become posttraumatic stress disorder in the third edition. By then we had the Korean War, the Vietnam War and their portrayals on television and in the movies with the Deer Hunter, Apocalypse Now, MASH and others.

I wonder if another reason the Army decided to suppress Let There Be Light was a 1946 movie with Dana Andrews, Myrna Loy and Fredric March called “The Best Years of Our Lives.” It told of the difficult and traumatic adjustments of three servicemen returning home after WWII. We see problems with alcoholism, unemployment and adultery. Samuel Goldwyn was inspired to make the movie after reading an article in Time about the problems experienced by men returning to civilian life. It won seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture. And it was the highest grossing and most attended film in the US and UK since Gone with the Wind.

These days ecstasy or MDMA is seen as a promising treatment for PTSD. The British medical journal The Lancet published a study of 26 individuals with chronic PTSD who were not helped by traditional methods. The New York Times reported “The improvements were so dramatic that 68 percent of the patients no longer met the clinical criteria for PTSD.” There were also improvements with sleep and becoming more conscientious.

The results, which mirror those of similar, small-scale studies of the illegal drug in recent years, come as MDMA is about to enter larger, Phase 3 trials this summer. Based on previous results, the Food and Drug Administration has given MDMA breakthrough therapy status, which could speed approval. If large-scale trials can replicate safety and efficacy results, the drug could be approved for legal use by 2021.

If approved by the FDA, MDMA would only be administered after three sessions of therapy by a licensed psychotherapist. During the fourth session, the patient takes the MDMA, and two therapists—one male and one female—are at the patient’s side as guides. Dr. Michael Mithoefer, lead author of The Lancet study said: “We encourage them to set aside all expectation and agenda and be open. Experiences tend to be very individual.” The drug releases hormones and neurotransmitters facilitating feelings of trust and wellbeing, allegedly allowing patients to re-examine traumatic memories.

The large-scale trials, which began in the summer of 2018, included up to 300 participants at 14 sites. Phase 3 trials are expected to cost $27 million. The funding comes from donations, not Pharma. David Bonner, of Dr. Bonner’s Magic Soaps, gave $5 million, as did an anonymous donor only known as Pine.

There is a possibility they will not be able to replicate the success of the previous trials. Yet there is a current lack of effective therapy for PTSD. “Only about one in three combat veterans with PTSD are effectively treated.”

The study was sponsored by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS). According to a MAPS press release, the study replicated previous research with an acceptable risk profile for MDMA. The most frequently reported adverse reactions were anxiety, headache, fatigue, and muscle tension.

MDMA was originally patented by Merck in 1912, but never marketed and the patent lapsed. The FDA would grant temporary data exclusivity to MAPS, giving it a five-year monopoly in the U.S. MAPS plans to funnel sales to a for-profit corporation, which would then return the money for more clinical research into the use of MDMA with other disorders. Rick Doblin, the founder of MAPS, has a vision for legalizing MDMA. See “Give MDMA a Chance?” for more on MAPS and Doblin.

But there are risks, despite the potential of MDMA. It can cause anxiety and increase stress. Chronic use may cause memory impairment. At high doses, it can cause your body to overheat. Chronic use may cause memory impairment. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) said MDMA affects the brain by increasing the activity of at least three neurotransmitters: serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. “Like other amphetamines, MDMA enhances release of these neurotransmittersand/or blocks their reuptake, resulting in increased neurotransmitter levels within the synaptic cleft (the space between the neurons at a synapse).” Releasing large amounts of serotonin causes the brain to become depleted of this neurotransmitter, contributing to the negative psychological aftereffects some people experience for several days after taking MDMA.

Low serotonin is associated with poor memory and depressed mood, thus these findings are consistent with studies in humans that have shown that some people who use MDMA regularly experience confusion, depression, anxiety, paranoia, and impairment of memory and attention processes. In addition, studies have found that the extent of MDMA use in humans correlates with a decrease in serotonin metabolites and other markers of serotonin function and the degree of memory impairment. In addition, MDMA’s effects on norepinephrine contribute to the cognitive impairment, emotional excitation, and euphoria that accompanies MDMA use.

Rick Doblin has been trying to achieve a legal justification for MDMA use for decades. Unlike Timothy Leary, he sought to embrace the dominant culture instead of turning on, tuning in, and dropping out. And he just may achieve his goal, with MDMA therapy for PTSD now in Phase 3 clinical trials. I suspect Doblin is not just trying to help facilitate more effective treatment for PTSD. Rather, it is a means to an end—an end parallel to that of Timothy Leary.

Leary first used the phrase “turn on, tune in, drop out” in a speech he gave on September 19,1966. His purpose was to encourage people to detach themselves from existing conventions in society by embracing the use of psychedelics. “Like every great religion of the past we seek to find the divinity within and to express this revelation in a life of glorification and the worship of God. These ancient goals we define in the metaphor of the present—turn on, tune in, drop out.” In his 1983 autobiography he explained what he had meant by the use of this metaphor:

“Turn on,” meant go within to activate your neural and genetic equipment. Become sensitive to the many and various levels of consciousness and the specific triggers that engage them. Drugs were one way to accomplish this end. “Tune in,” meant interact harmoniously with the world around you—externalize, materialize, express your new internal perspectives. “Drop out,” suggested an active, selective, graceful process of detachment from involuntary or unconscious commitments. “Drop Out” meant self-reliance, a discovery of one’s singularity, a commitment to mobility, choice, and change. Unhappily my explanations of this sequence of personal development were often misinterpreted to mean: “Get stoned and abandon all constructive activity.”

I suspect we will see more of the same if MDMA is approved for the treatment of PTSD.