Tranq Dope and Its Consequences

A church friend of mine was lamenting his recent visit to Philadelphia. He said that for a city with so many different historic sites, he thought the officials there should have done a better job keeping the sites cleaned up. One of the noticeable parts of the debris were used needles and syringes. This led to us exchanging comments on the opioid epidemic, and how fentanyl had made the situation even worse. What neither of us realized at the time was that our assessment wasn’t quite accurate. We had never heard of “tranq dope.”

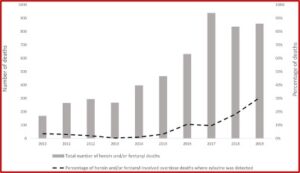

Although fentanyl has been replacing the heroin in the Philadelphia drug market, increasingly a substance known as xylazine has been found combined with fentanyl. It is a non-opioid veterinary tranquilizer that is not approved for human use. A brief report by Johnson et al, published in the journal Injury Prevention, reported that xylazine was detected in merely 2% of the unintentional overdose deaths in Philadelphia between 2010 and 2015. That rose to 11% in 2016; 18% in 2018 and 31% in 2019. See the chart below taken from the brief report.

NIDA (National Institute on Drug Abuse) said most overdose deaths linked to xylazine and fentanyl also involved other substances, including cocaine, heroin, benzodiazepines, alcohol, gabapentin, methadone and prescription opioids. When xylazine is taken in combination with other central nervous system depressants, it increases the risk of overdose.

Focus groups in Philadelphia said xylazine added to fentanyl gives the ‘nod’ that heroin provided before fentanyl took over the drug market. It “makes you feel like you’re doing dope (heroin) in the old days.” STAT News reported on paper published in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence that said while fentanyl produces a powerful high, its euphoria is short-lived when compared to other opioids like heroin. Adding xylazine gives fentanyl “legs,” meaning it extends the high.

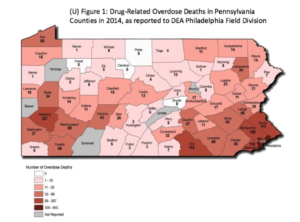

The newer study by Friedman et al noted xylazine use is spreading beyond the Philadelphia area. It was found increasingly present in overdose deaths in all four US Census Regions. The highest prevalence data was still in the North East, in Philadelphia (25.8% of deaths), followed by Maryland (19.3%), and Connecticut (10.2%). Disturbingly, xylazine-involved overdoses may resist naloxone since it isn’t an opioid. That’s not all. “People who used drugs with xylazine seem to be more susceptible to wounds and infections on their skin and other tissues.”

The arrival of xylazine is “when we started to see way more people coming in with necrotizing skin and soft tissue issues. The amount of medical complaints related to xylazine was pretty astounding and terrifying. Xylazine wounds are a whole other kind of … just horror.”

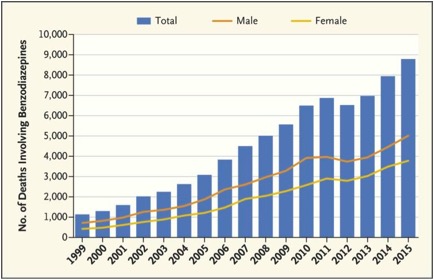

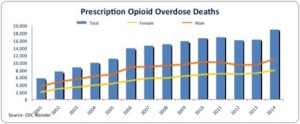

The term “opioid crisis” doesn’t really capture what is developing with overdoses in the U.S. over the past two years. It’s an overdose crisis of polysubstance use—opioids, stimulants, and benzodiazepines; often used in combination. Friedman was quoted by STAT News as saying xylazine was an “especially noxious contaminant that is spreading through the drug supply.” A CDC MMWR Report said during January-December of 2019, xylazine was found in the overdoses reported in 23 states. It was listed as the cause of death in 64.3% of deaths in which it was reported.

Xylazine, or “tranq dope” as it’s known on the streets in Philadelphia, is an analogue of clonidine, and is used for sedation, anesthesia, muscle relaxation and analgesia in animals. It seems to reduce sensitivity to insulin and glucose levels in humans. It can lead to diabetes mellitus and hyperglycemia. Its side effects include bradycardia (a slow, resting heart rate), respiratory depression, blurred vision, disorientation, drowsiness, fainting, slurred speech, staggering, and shallow breathing. Chronic use is associated with physical deterioration, abscesses and skin ulceration.

Since xylazine is FDA approved for veterinary use only, it is not a controlled substance by the DEA. It is available in liquid form and is structurally similar to phenothiazines (first generation antipsychotics).

Its human use in Puerto Rico was reported by Rafael Torruella in a short report for Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy in 2011. He said Puerto Rican injecting users had been using it since the early 2000s. There, it is called Anestesia de Caballo (Horse Anesthetic). The report contained descriptions of how xylazine was viewed from a drug user’s perspective. One individual said the following about the first time he used xylazine and his later physical dependence on both heroin and xylazine:

I shot the anestesia […] and I felt asleep face first and when I opened my eyes five hours had gone by and I was laying on the floor. […] I don’t remember anything. I don’t remember anything! I fell down and I was gone. And I said: What the hell is this?! Oh, and I woke up sick [withdrawing]!I get there and don’t cop just heroin. I cop anestesia. Because that it what is going to get me high and what is going to get me straight [and reverse withdrawal symptoms]. I am not going to waste my money in just heroin because I’m going to stay the same. Do you understand? I’m going to stay the same.

Torruella said abscesses or ulcers were a serious health concern for several reasons. First, they are very painful. This encourages further injections in the abscess site with xylazine functioning as a sedative/anesthetic. This creates a need for medical attention and treatment.

Second, these open skin ulcers ooze and emit a strong odor. In severe cases, the mobility of the extremities where they appear is limited. Sometimes, amputations have been performed on the affected limbs. Third, when xylazine users asked for help in Puerto Rico, they were denied services because of their ulcers. The drug user quoted above said he was lucky because by the time his abscesses developed, he had relocated to the states and could access medical services:

[T]he times when the abscesses […] started to appear, I would come here, to the United States. […] [When the abscesses began to appear] I already knew. […] I had seen them [before]. […] [T]here are people that take a longer time in blowing up [with abscesses] than others. […] I am one in which it took a while. But when I saw that people were rotting I would get scared because I always have said that I am a junky with style.

Without basic healthcare needs, like medical/wound care, syringe exchanges and education, these open sores look terrible to both the medically trained and the untrained-eye. When a colleague saw the ulcers and their effects on non-users, she said: “Injecting drug users are being treated as if they were lepers.”

According to NIDA, the full scope of overdose deaths involving xylazine is unknown. But research shows they have spread westward across the U.S. NIDA-supported research is underway to illuminate emerging drug use patterns and changes to the illicit drug supply across the U.S. with xylazine, opioids and the evolving pattern of polydrug use, abuse and overdose. Stay tuned for the next sea change.