When Pain Feels Good

Counter-intuitively, self-harm or self-injury is best seen as an attempt to relieve pain than to cause pain. An NPR program, “The History and Mentality of Self-Mutilation” noted that in the late 19th century, two American doctors described a strange phenomenon. Women were puncturing themselves with sewing needles. The practice was so common, that doctors began to refer to the so-called “hysterical” women who did this as “needle girls.” Hysteria was the “it” psychiatric condition of the time. Sigmund Freud’s first published book was one he co-authored with Josef Breur, Studies on Hysteria. But self-harm has a longer history, dating back even to the time of the Greeks.

Self-harm is found in situations as wide ranging as monasteries, nunneries and modern-day prisons. Within a religious context, the practice is called flagellation. The practice of mortifying the flesh for religious purposes within the Roman Catholic Church dates to 1054. Within Roman Catholic ritual, the fourth of the modern Stations of the Cross is the Flagellation of Christ. This station is based upon the scourging of Christ, just before he was delivered up to be crucified (Mark 15:15). Typically occurring before a crucifixion, scourging was with a cattail whip that had pieces of bone or metal tied into it.

In the 14th century, the Flagellants were condemned by the Roman Catholic Church as a cult. But a mild form is still practiced within a few strict monastic orders. And some members of the Catholic lay organization, Opus Dei, use a “discipline” during prayer. This is a cattail whip of knotted cords, which is repeatedly flung over the shoulders during private prayer. Reportedly, Pope John Paul II practiced this discipline regularly.

Armando Favazza, who has studied self-injury for several years, said its practitioners use it as a way to silence a swirl of pain and anxiety. “They describe it as popping a balloon. All the anxiety just seems to go away.” A 19 year-old woman interviewed in the NPR story said she has her own “kit”, consisting of a new pack of razors, a pair of scissors and a pink towel. Whenever she was stressed, she turned to her kit. Before cutting her mind is exploding. But when she feels pain, there’s a kind of peace. “I’ll just be really calm and my thoughts will finally kind of be making sense, instead of them like racing through my head and nothing quite clicking. Just kind of centralizes my thought on one thing.”

A 2010 article, “Self-Injurious Behavior in Adolescents” by Janis Whitlock defined self-injury or non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) as “the deliberate, self-inflicted destruction of body tissue without suicidal intent and for purposes not socially sanctioned.” Most often, it is not a suicidal gesture, while it can result in severe harm or death. Studies tend to find what is referred to as common NSSI in 12% to 37.2% of American high school-aged individuals and 12% to 20% of late adolescent and young adult populations. “Overall, about a quarter of all adolescents and young adults with NSSI history report practicing NSSI only once in their lives.” The available evidence suggests that 40% of repeat NSSI report stopping within the first year, and 79.8% report stopping within 5 years of starting.

Unpublished data indicates females are slightly more likely to practice self-harm than males. In my counseling experience, I’ve talked with both males and females who attempted NSSI. This is also not an isolated American phenomenon. NSSI is present in a variety of countries and cultures globally. “Although most widely investigated in industrialized regions such as Europe, North America, Australia, and New Zealand, NSSI also occurs with some regularity in other industrialized and non-industrialized countries as well.”

Self-injury is strongly linked to childhood abuse, especially childhood sexual abuse; eating disorders, substance abuse, PTSD, depression and anxiety. While it is common among adolescents, NSSI often goes undetected. Some signs can include wearing long sleeves or pants during hot weather; constant use of wristbands/coverings, unwillingness to participate in activities with less body coverage, like swimming or gym class; and frequent bandages. Whitlock also highlighted what she saw as five key studies of NSSI. See her linked article for the details.

Moran et al. published a natural history study of self-harm in the British journal The Lancet in 2012. More girls (10%) than boys (6%) reported self-harm in adolescence. There was a substantial reduction of self-harm during late adolescence. During adolescence, self-harm was associated with depression and anxiety, antisocial behavior, high-risk alcohol use, cannabis use and cigarette smoking. While most adolescent self-harm resolved spontaneously, when mental health issues are associated, treatment mat be needed.

Most self-harming behaviour in adolescents resolves spontaneously. The early detection and treatment of common mental disorders during adolescence might constitute an important and hitherto unrecognised component of suicide prevention in young adults.

A Cochrane study by Hawton et al. in 2015 looked at pharmacological treatment for self-harm. The conclusion was: “There is currently no clear evidence for the effectiveness of antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilisers, or natural products in preventing repetition of SH [self-harm].” They found no significant treatment effect for newer antidepressants, fluphenazine (an antipsychotic), mood stabilizers or natural products. While a significant reduction in self-harm behavior was found with flupenthixol (an antidepressant), the quality of the evidence for the study was very low. No data on adverse effects, other than the planned outcomes related to suicidal behavior, were reported.

We have reviewed the international literature regarding pharmacological (drug) and natural product (dietary supplementation) treatment trials in this field. A total of seven trials meeting our inclusion criteria were identified. There is little evidence of beneficial effects of either pharmacological or natural product treatments. However, few trials have been conducted and those that have are small, meaning that possible beneficial effects of some therapies cannot be ruled out.

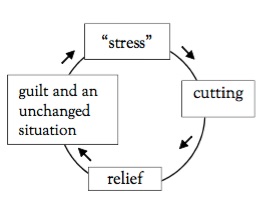

In a 2004 article in The Journal of Biblical Counseling, “Self-Injury: When Pain Feels Good,” Ed Welch said anything that arouses unwanted emotions can trigger the self-harm cycle. Trouble in relationships or anything that can provoke shame could be triggers. Beliefs that you have violated a personal, cultural or religious taboo can initiate it. “Perhaps you just don’t tolerate your own humanness with its imperfections, weaknesses, dependencies and sins.” Welch described the cycle of self-harm as following the pattern in this graphic:

These beliefs, personal experiences, and external circumstances mix into a stew of raw emotions that can include anger and frustration, anxiety, or a jumping-out-of-your-skin agitation. Without alternatives, self–injury gradually becomes the preferred response to these feelings because it works. You regain control. Your emotions are back in check. The screams within have been temporarily silenced.

Welch is approaching the issue of self-harm from a biblical, religious perspective. So his advice and action steps will include addressing the spiritual side of self-harm: “Self-injury is, at its root, about God. Avoid Him, and we miss true hope.” In order to address self-injury: 1) Allow other people in; ask for help. 2) Grow in honesty; don’t hide your behavior. 3) Feed yourself with Scripture; the Psalms are a good place to start. 4) Write out the meaning and purpose of your self-injury. 5) When you fail, don’t give in to hopelessness. “All human beings sin and fail. It is what we do!” 6) If you keep moving back into self-injury, notice the intentionality of your behavior. Are you putting barriers between yourself and your self-abuse strategies?

If you are interested in the complete article by Ed Welch, you can purchase it in booklet form on Amazon or at the Christian Counseling and Education Foundation (CCEF). If you purchase it in its original form in The Journal of Biblical Counseling, you can purchase the full digital issue it appeared in (JBC Volume 22:2).