A Misbegotten Stepcousin of Christianity, Part 2

Christian Smith with Melinda Lundquist Denton introduced the term ‘moralistic therapeutic deism’ (MTD) in their 2005 book, “Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers” to describe what they see as the common beliefs among American youths. Yet it seems to echo a distinction between religion and spirituality that can be traced back to the thought of William James in The Varieties of Religious Experience, which has been in print since 1902. In Part 1 of this article, I looked at the meaning of MTD and here will examine how it emerged from the sense of ‘spiritual not religious’ belief in Alcoholics Anonymous that grew out of James’ Gifford Lectures on the psychological study of individual religious and spiritual experience.

In “’Being Religious’ or ‘Being Spiritual’ in America,” Marler and Hadaway looked at five different surveys done between the late 1980s and 2000 that asked respondents whether they considered themselves to be “religious” or “spiritual.” Are Americans less religious and more spiritual? They concluded the studies could not give a definitive answer. “The most significant finding about the relationship between ‘being religious’ and ‘being spiritual’ is that most Americans see themselves as both.” When potential change can be traced by examining successive age groups, or by comparing more with less churched respondents, “the pattern is towards less religious and less spirituality.”

The net effect is that among less churched and younger Americans there is less agreement about religiousness and spirituality, and change is observed more in the decline of those Roof (2000) identifies as ‘strong believers,’ the religious and spiritual, and the increase in ‘secularists.’

Nevertheless, the Pew Research Center said “More Americans now say they’re spiritual but not religious.” In 2017, Pew noted that 27% of U.S. adults think of themselves as spiritual but not religious, an increase of 8% since 2012. This growth was broad-based, increasing among men and women; Republicans and Democrats; across race/ethnicity; and people of different ages and education levels. It seems to have come mainly at the expense of Americans who considered themselves to be spiritual and religious. The percentage of U.S. adults who say they are spiritual and religious fell by 11 points between 2012 and 2017. See the following graphic to the left taken from the Pew article.

While many of U.S. adults are religiously unaffiliated, describing themselves as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular”, most actually do identify with a religious group. Many in the “spiritual but not religious” category have low levels of religious observance, saying they seldom or never attend religious services; and that religion is “not too” or “not at all” important in their lives. Yet others say they attend religious services weekly and 27% say religion is very important to them. See the following chart to the right taken from the Pew article.

While many of U.S. adults are religiously unaffiliated, describing themselves as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular”, most actually do identify with a religious group. Many in the “spiritual but not religious” category have low levels of religious observance, saying they seldom or never attend religious services; and that religion is “not too” or “not at all” important in their lives. Yet others say they attend religious services weekly and 27% say religion is very important to them. See the following chart to the right taken from the Pew article.

Smith and Denton acknowledged the widespread sense of “spiritual seeking” by people who consider themselves as “spiritual but not religious.” They are people who have an interest in spiritual matters but are not devoted to one particular historical spiritual faith or denomination. They are reportedly exploring many faiths and spiritualities in order to find what works for them, that meets their needs. They are open to a multiplicity of truths, willing to mix and match traditionally distinct religious beliefs and practices. “And they are suspicious of a commitment to a single religious congregation.”

They operate, whether self-consciously or not, as religious and spiritual consumers by defining themselves as individual seekers, the authoritative judges of truth and relevance in faith according to how things subjectively feel to them. Such consuming seekers are not religiously rooted or settled but are spiritual nomads on a perpetual quest for greater insight and more authentic and fulfilling experiences.

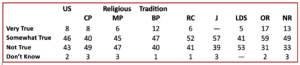

When Smith and Denton looked at whether American teenagers consider themselves to be spiritual but not religious, only 8 percent said it was very true of them. Forty-six percent said it was somewhat true and 43% said it is not true at all. They also presented data that broke this down further by religious tradition. In the following chart, CP stands for conservative Protestant, MP for mainline Protestant, BP for Black Protestant, RC for Catholic, J for Jewish, LDS for Ladder Day Saints/Mormons, OR for other religions, and NR for not religious.

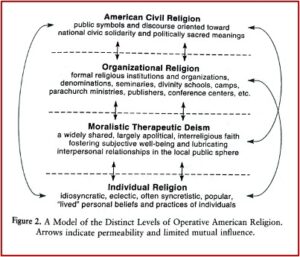

Smith and Denton would likely explain the difference between their research with teenagers and that from the Pew Center with adults as a product of the teens not understanding the meaning of “spiritual but not religious.” The majority of the teens they interviewed for their study said they had never heard the term before. And if they had heard of the term, they had no clue what it meant. “Although the slogan ‘spiritual but not religious’ can be seen on many bookshelves, read in many newspapers, and heard on many talk shows, very few American teenagers have heard of it, much less learned to what beliefs and lifestyles it refers.” So, they coined the term ‘moralistic therapeutic deism’ to capture what they saw as the basics of teen-centered belief system and suggested it operated as a distinct level within American Religion.

Smith and Denton would likely explain the difference between their research with teenagers and that from the Pew Center with adults as a product of the teens not understanding the meaning of “spiritual but not religious.” The majority of the teens they interviewed for their study said they had never heard the term before. And if they had heard of the term, they had no clue what it meant. “Although the slogan ‘spiritual but not religious’ can be seen on many bookshelves, read in many newspapers, and heard on many talk shows, very few American teenagers have heard of it, much less learned to what beliefs and lifestyles it refers.” So, they coined the term ‘moralistic therapeutic deism’ to capture what they saw as the basics of teen-centered belief system and suggested it operated as a distinct level within American Religion.

While they acknowledged how the thought of Robert Bellah was incorporated into their level of American Civil Religion, they failed to note the correspondence of their levels of Organizational Religion and Individual Religion to William James’ distinction between institutional and personal religion. See the chart for Figure 2 in Part 1.

In VRE, James said worship, sacrifice, ritual, theology, ceremony and ecclesiastical organization were the essentials of institutional religion. He defined personal religion as “the feelings, acts, and experiences of [the] individual . . . in their solitude, so far as they apprehend themselves to stand in relation to whatever they may consider the divine.” James’ sense of institutional religion fits with Smith’s and Denton’s sense of organizational religion (as formal religious institutions and organizations), as his sense of personal religion fits with their sense of individual religion (as the idiosyncratic, eclectic, “lived” beliefs and practices of individuals).

James said that if someone thought the word ‘religion’ should be reserved for the fully organized system of feeling, thought, and institution typically called the church, he invited them to refer to what he called personal religion whatever they wanted. Alcoholics Anonymous began calling it spirituality, where Smith and Denton referred to it as moralistic therapeutic deism.

We live at a time when religious belief in America, particularly Christian religious belief, has been increasingly questioned and challenged as too rigid or doctrinaire. This is especially true for conservative Christians, who are attempting to live by and apply what they see as the teachings of Scripture to their lives during this turbulent time. In “Religious Alcoholics; Anonymous Spirituality” I suggested that the Jamesean distinction of religion and spirituality fails to separate a Christian expression of religion from a non-Christian one, and a biblical sense of spirituality from a nonbiblical one. A richer and nuanced distinction would be between true spirituality and mere spirituality and true religion and mere religion, remembering that “true religion always contains true spirituality.”

In True Spirituality, Francis Schaeffer rejected the possibility that true spirituality could be devoid of biblical content. There cannot be a leap-in-the-dark faith for a Christian; there is no “faith in faith” encounter with the divine. Schaeffer said, “It is believing the specific promises of God, no longer turning our backs on them, no longer calling God a liar, but raising empty hands of faith and accepting that finished work of Christ as it was fulfilled in history on the cross.”

As Smith and Denton said with regard to moralistic therapeutic deism, under the influence of mere religion and mere spirituality, Christianity is degenerating into a pathetic, misbegotten stepcousin of itself. Or worse, it is being displaced by a different religious faith.

I’ve previously described how the sense of ‘spiritual not religious’ found in Alcoholics Anonymous emerged from The Varieties of Religious Experience by William James in several other articles on this website. Search for ‘spiritual not religious,’ on this website. You can start with three related articles, beginning with “What Does Religious Mean?” There are links to the remaining two articles at the end of the article.