Protestants Without Sola Fide, Part 1

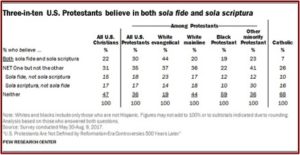

Five hundred years ago, Martin Luther is credited with sparking the Protestant Reformation when he nailed his 95 Theses to the door of All Saints Church in Wittenberg. Classically, there were two fundamental ideas that drove Luther: sola fide, meaning that justification is dependent upon faith alone; and sola scriptura, that Scripture is the only ultimate authority for Christian belief and practice. There were other concerns over religious practices such as the sale of indulgences, but sola fide and sola scriptura “became the rallying cry for many Protestant reformers.” Yet a recent Pew Research study suggested less than half of U.S. Protestants (46%) affirmed a belief in either doctrine, and only 30% affirmed a belief in both; another 36% did not believe in either sola fide or sola scriptura. This raises the question, are modern Protestants no longer Protestant?

A Pew study, “U.S. Protestants Are Not Defined by Reformation-Era Controversies,” found that half of American Protestants (52%) thought that both good deeds and faith in God were needed to get to heaven. The same percentage (52%) also agreed that in addition to the Bible, Christians needed guidance from church teachings and traditions. While Protestants are almost evenly split on sola fide and sola scriptura, U.S. Catholics are mostly aligned with the teachings of the Catholic Church, which affirms both of these declarations. Eighty-one percent believe both good deeds and faith in God are needed to get into heaven and 75% agree that in addition to the Bible, Christians need guidance from church teachings and traditions. “Overall, two-thirds of Catholics take the traditional positions of the church on both of these issues.”

Among Protestant subgroups, two-thirds (67%) of white evangelicals say salvation comes by faith alone, with 33% saying that both faith and good works are needed. White evangelicals also had the highest percentage of believers in both sola fide and sola scriptura (44%). See the following chart from the Pew Research Center report.

Above sola fide was said to mean: “justification is dependent upon faith alone.” This doctrine reaches back to Martin Luther and his understanding of Galatians 3:28, “For we hold that one is justified by faith apart from works of the law.” Luther’s theological insight here was the heart of his personal spiritual change and his theology that followed. In The Encyclopedia of Christianity, Notger Slenczka added the following:

Above sola fide was said to mean: “justification is dependent upon faith alone.” This doctrine reaches back to Martin Luther and his understanding of Galatians 3:28, “For we hold that one is justified by faith apart from works of the law.” Luther’s theological insight here was the heart of his personal spiritual change and his theology that followed. In The Encyclopedia of Christianity, Notger Slenczka added the following:

This exclusion of works as a ground of justification does not mean the isolating of faith but singles out justifying faith because it receives the righteousness of Christ that is given by grace alone. The formula thus has the implication of solus Christus (Christ alone) and sola gratia (grace alone).

But here is where it gets a bit tricky theologically. The Pew study said sola fide was: “faith in God alone is needed to get into heaven,” but getting into heaven is related to salvation. The statement alone is true as far as it goes (“For by grace you have saved through faith”, Ephesians 2:8), but the problem is where Pew equated it with the Reformation principle of sola fide. In doing so, Pew confounded what has historically been a crucial theological distinction between the Protestant and Catholic understanding of the doctrine of justification by faith. In the Lexham Bible Dictionary, Michael Bird gave the following explanation of differences between Catholics and Protestants on justification by faith:

The primary debate between Protestants and Catholics is whether justification is a forensic declaration based on the imputation of Jesus’ righteousness to believers [Protestants], or based on the infusion of righteousness into the believer through the sacraments, enabling them to do works of charity by which they might be justified [Catholics]. . . . While fresh new ecumenical ground has been broken, thus far no consensus has been reached. The Catholic Catechism remains firmly committed to the teachings of the Council of Trent, which remains a barrier to any consensus emerging.

The Council of Trent stated in Chapter VII about justification: “[It] is not only a remission of sins but also the sanctification and renewal of the inward man through the voluntary reception of the grace and gifts whereby an unjust man becomes just and from being an enemy becomes a friend, that he may be an heir according to hope of life everlasting.”

In Reformed Dogmatics, Geerhardus Vos added the following aboiut the Roman Catholic understanding of justification:

The Roman Catholic church makes a distinction between a first and a second justification. The first consists in the infusion of habitual grace, by which original sin is suppressed and expelled. The formal cause of the second justification is to be sought in good works that man himself performs. This is a confusion of sanctification and justification, and makes the fruits of the former meritorious. As justification becomes sanctification, so sanctification again becomes justification in the hands of Rome—naturally, a legalistic justification.

With regard to second justification, Roman Catholicism said in the Council of Trent: “If anyone says that the justice received is not preserved and also not increased before God through good works, but that those works are merely the fruits and signs of justification obtained, but not the cause of its increase, let him be anathema.” What Roman Catholicism condemned here is the clear Protestant understanding of sola fide, justification by faith alone.

My systematic theology is not sharp enough to have picked out that problem with the Pew survey on my own. I read an article by Joe Carter for The Gospel Coalition, “New Survey Finds Majority of Protestants Are (Maybe) Not Protestant,” that brought the Pew study and how it framed sola fide to my attention. He updated his original article on the Pew survey, as he himself had missed the Pew Research Center’s “mistake.” He explained how he originally read the Pew description as referring to justification, which a theologically minded Protestant who associates sola fide and justification by faith, would do. Here is an example of what Pew said that was confusing: “For example, nearly half of U.S. Protestants today (46%) say faith alone is needed to attain salvation (a belief held by Protestant reformers in the 16th century, known in Latin as sola fide).”

As Carter pointed out, belief in sola fide was determined by how Christian respondents answered the following question in the Pew survey: “Which statement comes closer to your view, even if neither is exactly right?” Their choices were: 1) “Both good deeds and faith in God are necessary to get into heaven” and 2) “Faith in God is the only thing that gets people into heaven.” Similarly, sola scriptura was determined by how they responded to this question: “Which statement comes closer to your view, even if neither is exactly right?” Their choices were: 1) The bible provides all the religious guidance Christians need” and 2) In addition to the Bible, Christians also need religious guidance from church teachings and traditions.” See the “Survey Questionnaire” attached to the Pew Research Center article on the survey.

Carter went on to indicate he thought there was a priming bias in how the survey questions here were worded, meaning “the types of questions that are asked tend to prime a respondent to assume later questions are of the same type.” This led him to conclude that respondents were set up to look for a distinction between what Protestants and Catholics believe. His own mistake was evidence of that. “ I was primed to follow Pew’s reasoning even though when I wrote this article I was explicitly on the lookout for the effects of priming on the survey results.”

He concluded that it was impossible to know based on these results how many people are “pseudo-Protestants” and how many (like him) were reading too much into the survey questions. “The conclusion I draw is that some people were reading the question as I did as being about justification, while many others were seeing it as merely about salvation.” Given this confusion, it might be helpful to have a more comprehensive discussion of sola fide.

In his article for Themelios, “Is the Reformation Over?” Scott Mantesch noted how John Calvin believed the doctrine of justification held an essential place in the Christian gospel. He also believed it was one of the most significant issues separating Protestants and Catholics, saying it was “the first and keenest subject of controversy between us.” While Calvin emphasized that justification must be distinguished from regeneration or sanctification, he still insisted that justifying faith necessarily resulted in spiritual renewal and growth in godliness. While it is faith alone that justifies, “yet the faith which justifies is not alone.” Calvin said:

As God justifies us freely by imputing the obedience of Christ to us, so we are rendered capable of this great blessing only by faith alone. As the Son of God expiated our sins by the sacrifice of his death, and by appeasing his Father’s wrath, acquired the gift of adoption for us, and now presents us with his righteousness, so it is only by faith we put him on, and become partakers of his blessings.

Not only is justification by faith doctrinally important, it is pastorally vital. In order to illustrate this point, Thomas Schreiner, who, wrote Faith Alone: The Doctrine of Justification, asked when we stand before God on Judgment Day, what will we plead before him? “Will we plead our own righteousness and goodness?” The doctrine is not a matter of indifference.

Thomas Schreiner is a New Testament professor at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. At a 2015 Theology Conference on The Five Solas, he read a paper summarizing his book. All the papers presented at the conference can be found here, in an edition of The Southern Baptist Journal of Theology. There is also a link to a video of Schreiner’s presentation under The Gospel Coalition’s page on The Five Solas.

He said the shorthand phrase of sola fide, meaning justification by faith alone, “summarizes in short form the theology that has been hammered out exegetically, historically, and theologically.” An untutored individual may think this means that good works are not necessary or important. But when most advocates say that justification is by faith alone, they quickly add that such faith is never alone. “Hence, when they affirmed that justification was by faith alone, they were ruling out the notion that our works were a basis of justification. So, the slogan justification by faith alone is useful as long as it is rightly understood.”

When we speak of justification by faith alone, we aren’t saying that our faith justifies us. We see here how the five solas are closely linked together, for righteousness is by faith alone because our righteousness is in Christ alone as the crucified and risen one. And if our righteousness is by faith alone and in Christ alone, then it is by grace alone since our works don’t constitute our righteousness. And our righteousness is also to the glory of God alone since he is the one who has accomplished our salvation. Justification by faith alone doesn’t call attention to our faith but to Christ as the redeemer, reconciler, and Savior. [As an aside in the video, Schreiner noted he didn’t mention sola Scriptura. “But everything I said supported that.”]

Schreiner observed that Roman Catholics believe that justification comes in part from our adherence to the moral law. They will point out that the Scriptures only address whether justification is by faith alone once in James 2:24 in the negative: “You see that a person is justified by works and not by faith alone.” But Schreiner argued that in James 2:14-26, James is rejecting a saying faith, a faith where works are absent. “It is this kind of faith that doesn’t save, for it is a faith marked by intellectual assent only.” When James says faith without works doesn’t save, he is thinking of a “dead” faith (2:17, 26), a useless or idle faith (2:20).

But genuine faith, a faith that embraces all that God is for us in Jesus Christ, saves, and such a faith inevitably produces works. But this accords what we mean when we speak of sola fide. We are justified by faith alone and yet our faith is never alone.

The problem may have been that Pew researchers believed (in all likelihood correctly) that the typical person taking the survey would not have previously heard of, or understood, the differences between the Catholic and Protestant views of sola fide, the doctrine of justification by faith alone. So they redefined sola fide as described above, and chose to not use the term “sola fide” in the questionnaire. Apparently Pew thought the phrase: “Which statement comes closer to your view, even if neither is exactly right,” was enough to guide those individuals who did understand the classic sense of sola fide to their redefinition. Given Joe Carter’s confusion and that of others (See the endnote “correction” for Sarah Eekhoff Zylstra’s article on the same Pew survey in Christianity Today), it was not.

If Carter and other Protestants could misread or confuse the Pew “mistake” with sola fide, doesn’t that add further validity to the point of the Pew article? Namely, there may be a significant number of American Protestants who are Protestant in name, but not necessarily Protestant in theology. What then does it mean to be “Protestant” in theology, and how does that differ from Roman Catholicism? We’ll examine these questions in Part 2 of this article.