Blind Spots with Antipsychotics, Part 1

Carrie Fisher was flying back to her home in Los Angeles on December 23, 2016 when she went into cardiac arrest. She was removed from the plane and later died in the hospital. Her daughter, Billie Lourd, said: ““She was loved by the world and she will be missed profoundly.” She was a well-known actress, writer and humorist. She wrote six books, some of which described her life, loves and adventures, which included drug addiction and bipolar disorder. A series of articles lamented that she was taken too soon, but there wasn’t anything said about a possible connection between her sudden cardiac death (SCD) and the medication she took for her bipolar disorder.

Fisher was a vocal mental health advocate and talked freely about her bipolar disorder and over the years. An article contained the following statements made by Fisher about her mental health and use of medication. In an interview with Diane Sawyer in December of 2000, she said: “I am mentally ill. I can say that. I am not ashamed of that. I survived that, I’m still surviving it, but bring it on. Better me than you.” At a February 2001 rally in Indianapolis for increased state funding for mental health and addiction treatment, she said: “Without medication I would not be able to function in this world. Medication has made me a good mother, a good friend, a good daughter.”

Writing for Mad in America, Corinna West raised the question of whether Fisher’s too soon passing was related to her use of psych meds. West referred to an article in the European Heart Journal by Honkola et al. that concluded: “The use of psychotropic drugs, especially combined use of antipsychotic and antidepressant drugs, is strongly associated with an increased risk of SCD at the time of an acute coronary event.” Variety reported Carrie Fisher was taking Prozac (an antidepressant), Abilify (an antipsychotic) and Lamictal (a mood stabilizer).

This study confirms that combining antidepressants and old school [first generation] antipsychotics causes an 18-fold increase in death during a cardiac event. Combining antidepressants with any antipsychotic causes an over 5-fold increase in relative risk of death during a cardiac incident.

To put this into some context, West noted: “Vioxx was pulled from the market for a 2-fold increase in relative risk factor of strokes and heart attacks.” It may have led to the death of 50,000 to 70,000 people while it was on the market. She then did some speculative calculations and suggested psych meds may contribute to 74,191 additional heart attacks annually and 33,386 deaths from SCD per year.

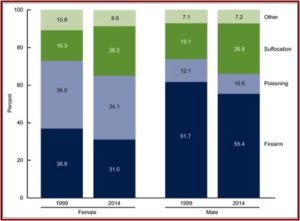

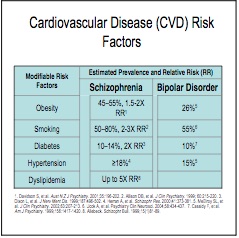

She also noted how people with serious mental illness have a 25-year lower life expectancy than others and a significantly greater risk of myocardial infarction. The NASMHPD “Morbidity and Mortality Report” said that it has been known for several years that people with serious mental illness die younger than the general population. “In fact, persons with serous mental illness (SMI) are now dying 25 years earlier than the general population.” The report also said people with SMI also suffer from a greater percentage of modifiable risk factors associated with cardiovascular disease, such as obesity, smoking, diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidema (high cholesterol). Corrine West noted the data from the “Morbidity and Mortality Report” showed that psychiatric drugs increased 4 of the top 5 normal risk factors for cardiac disease. Smoking was included as a risk factor because many individuals using psych meds find the nicotine helps relieve some of the numbness caused by the meds. See the following chart from the report.

There is increasing evidence of multiple adverse effects from the long-term use of antipsychotics in addition to the risk of SCD. Murray et al. concluded there was a lack of evidence for the long-term effectiveness of prophylactic (maintenance) antipsychotic use; and a growing concern with the cumulative effects of antipsychotics on physical health and brain structure. “There is enough evidence concerning the adverse effects of antipsychotics on physical health to compel psychiatrists to act.”

There is increasing evidence of multiple adverse effects from the long-term use of antipsychotics in addition to the risk of SCD. Murray et al. concluded there was a lack of evidence for the long-term effectiveness of prophylactic (maintenance) antipsychotic use; and a growing concern with the cumulative effects of antipsychotics on physical health and brain structure. “There is enough evidence concerning the adverse effects of antipsychotics on physical health to compel psychiatrists to act.”

Murray et al. said long-tem maintenance treatment with antipsychotics was “based on hope rather than evidence.” They pointed to two serious methodological problems. First, studies claiming that antipsychotic maintenance treatment substantially reduced the risk of relapse were often limited to two years of follow-up. Second, the studies compared schizophrenic patients continuing on antipsychotics with those who stopped taking antipsychotics, not individuals who never used the drugs. So the withdrawal effect from antipsychotics in the discontinuation group influenced the higher relapse rates, making it a confounding variable to the supposed positive results with antipsychotic maintenance treatment.

The Murray et al. researchers did think there was no clear link between antipsychotic-associated changes in brain structure and cognitive decline or functional impairment. However, studies like that of Ho et al. suggested antipsychotics can “have a subtle but measurable influence on brain tissue loss over time.” Ho et al. said there was also a problem with dopamine receptor supersensitivity in some antipsychotic users. This supersensitivity could be a factor in the decreased efficacy of antipsychotics with continued prescription; and it may contribute to relapse when an individuals stops using antipsychotics. “There is an urgent need for neurochemical imaging studies addressing the question of dopamine supersensitivity in patients.” In their conclusion, the researchers gave the following recommendations.

[The wise psychiatrist] will treat acute psychosis with the minimum necessary dose of antipsychotics, employing weight sparing antipsychotics wherever possible; dopamine partial agonists have this property and may also be less likely to induce dopamine supersensitivity. Following recovery, the psychiatrist should work with each patient to decrease the dose to the lowest level compatible with freedom from troublesome psychotic symptoms; in a minority of patients, this level will be zero.

You can read a summary review of the study by Justin Karter on Mad in America here.

Not all of the above-cited researchers agreed with the conclusions of each other. But collectively they pointed to evidence of a link between antipsychotics and adverse cardio vascular events, brain shrinkage, and dopamine supersensitivity. Murray et al. also suggested that studies of long-tem antipsychotic maintenance treatment unfairly stacked their results in favor of antipsychotic maintenance by using patients who were withdrawn/discontinued from using antipsychotics as their control group. So when the recent press release from Columbia Medical Center regarding Goff et al. concluded the benefits of antipsychotics outweigh the risks was disconcerting and confusing at first. The Goff et al. abstract asserted: “Little evidence was found to support a negative long-term effect of initial or maintenance antipsychotic treatment on outcomes, compared with withholding treatment.”

The press release acknowledged the above concerns that antipsychotic medications have been said to have toxic effects and negatively impact long-term outcomes. However it went on to say that if this view was not justified by data, it had the potential to “mislead some patients (and their families) to refuse or discontinue antipsychotic treatment.” Therefore a team of researchers led by Jeffrey Lieberman, the Lawrence C. Kolb Professor and Chairman of Psychiatry at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeon, undertook “a comprehensive examination of clinical and basic research studies that examined the effects of antipsychotic drug treatment on the clinical outcomes of patients and changes in brain structure.” Lieberman was liberally quoted in the Columbia press release with regard to their findings supporting how the benefits of antipsychotics outweigh the risks. He said:

The evidence from randomized clinical trials and neuroimaging studies overwhelmingly suggests that the majority of patients with schizophrenia benefit from antipsychotic treatment, both in the initial presentation of the disease and for longer-term maintenance to prevent relapse. . . . Anyone who doubts this conclusion should talk with people whose symptoms have been relieved by treatment and literally given back their lives.

Lieberman went on to suggest that only a very small number of individuals recover from an initial psychotic episode without the use of antipsychotic maintenance treatment. “Consequentially, withholding treatment could be detrimental for most patients with schizophrenia.” He acknowledged where rodent studies suggested antipsychotics can sensitize dopamine receptors, but “there is no evidence that antipsychotic treatment increases the risk of relapse.” Further, although antipsychotic medications can increase the risk of metabolic syndrome, which is linked to heart disease, diabetes and stroke, their study did not include a risk benefit analysis of this concern.

Wait a minute. Why didn’t their study include a risk benefit analysis for metabolic syndrome? It seems to be one of the most reliably documented adverse effects, as noted above. Could it be that the intended message of the research—namely how strong evidence supports the benefits of antipsychotic medications—would not have been as clearly communicated if the risk benefit analysis concluded there was a substantial risk of metabolic syndrome? By the way, according to the Mayo Clinic,

Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of conditions — increased blood pressure, high blood sugar, excess body fat around the waist, and abnormal cholesterol or triglyceride levels — that occur together, increasing your risk of heart disease, stroke and diabetes. Having just one of these conditions doesn’t mean you have metabolic syndrome. However, any of these conditions increase your risk of serious disease. Having more than one of these might increase your risk even more. If you have metabolic syndrome or any of its components, aggressive lifestyle changes can delay or even prevent the development of serious health problems.

Dr. Lieberman has been a vocal advocate of modern psychiatry and equally critical of those who question many of its claims, as with those documented here. My previous encounters with his presentation of evidence and data, like his discussion of the conclusions of Goff et al. above, have led me to be skeptical of his conclusions without further investigation. I believe his fervent desire to defend modern psychiatry and current psychiatric methods has distorted how he interprets and presents conflicting evidence. He seems to have a blind spot when assessing and interpreting evidence counter to his position. The above question about the failure to include a risk benefit analysis of metabolic syndrome is one illustration of what I mean.

So what do others have to say with regard to the Goff et al. study? We’ll look at some of those critiques in Part 2 of this article.