Conjuring the Antidepressant Effect of Ketamine

Ketamine use and abuse has been getting several different kinds of media attention lately. The DEA and the Los Angeles police are investigating how Matthew Perry received the ketamine that killed him. Perry was undergoing ketamine infusion therapy under the care of a psychiatrist and an anesthesiologist. However, his last infusion therapy was 10 days before his death and wouldn’t explain the levels of ketamine found in his autopsy. The amount of ketamine in his blood was approximately that for general anesthesia during surgery and was listed as the primary cause of his death.

Ketamine is known as a “dissociative anesthetic hallucinogen” because it makes the person feel detached from their pain and environment. It distorts the perception of sight and sound, making the user feel disconnected and not in control. It can induce sedation (feeling calm and relaxed), immobility, pain relief, and amnesia—no memory of events while under the influence of the drug. Not surprisingly, ketamine has also been used in sexual assault. And an overdose can cause unconsciousness and dangerously slowed breathing, as it seems to have done with Matthew Perry.

Ketamine became a popular “club drug” known as Special K, Kit Kat, Super K, and others. It’s typically distributed at raves, nightclubs and private parties; and rarely sold on the street. The illegal use of ketamine in the U.S. is diverted or stolen from veterinary clinics or smuggled into the country from Mexico. It comes in a clear liquid that can be mixed into drinks, or as a white or off-white powder that is snorted or smoked, typically with marijuana or tobacco.

Ketamine produces hallucinations. It distorts perceptions of sight and sound and makes the user feel disconnected and not in control. A “Special K” trip is touted as better than that of LSD or PCP because its hallucinatory effects are relatively short in duration, lasting approximately 30 to 60 minutes as opposed to several hours.

The onset of effects is rapid and often occurs within a few minutes of taking the drug, though taking it orally results in a slightly slower onset of effects. Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder (HPPD) has been reported several weeks after ketamine is used and may include experiencing the negative side effects that occurred while taking the drug initially. Ketamine may also cause agitation, depression, cognitive difficulties, unconsciousness, and amnesia.

In an interview, Elon Musk discussed his prescription use of ketamine. He said he uses a small amount once every week or so. “There are times when I have sort of a … negative chemical state in my brain, like depression I guess, or depression that’s not linked to any negative news, and ketamine is helpful for getting one out of the negative frame of mind.” He denied any misuse of ketamine, saying, “if you use too much ketamine, you can’t really get work done. I have a lot of work. I’m typically putting in 16-hour days … so I don’t really have a situation where I can be not mentally acute for an extended period of time.”

Ketamine is not an FDA-approved treatment for depression but some psychiatrists use it off-label. Ketamine infusion therapy, like that prescribed to Matthew Perry, is not covered by insurance, meaning it’s expensive. And not every psychiatrist is willing to prescribe it. A derivative of ketamine known as esketamine (Spravato) was approved in 2019 as a nasal spray. But receiving a ketamine infusion or Spravato requires close medical supervision in a clinic.

This expense and the “inconvenience” of medical supervision led to the proliferation of compounded ketamine products such as ketamine lozenges and tablets and nasal sprays from a multitude of online sources, allowing for the at-home use of ketamine, which seems to be what contributed to Matthew Perry’s accidental death. The FDA published an alert, warning of the potential danger of compounded ketamine products. “Compounded drugs are not regulated by the FDA, so there is no assurance the drugs purchased from a compounding pharmacy are what the companies claim they are.” They pose a higher risk to patients than FDA-approved drugs because they don’t undergo the FDA review for safety, effectiveness and quality.

Now there has been the publication of a phase 2 clinical trial for extended-release ketamine tablets for treatment-resistant depression in the journal Nature Medicine. The lead author of the study told Medscape, “Having a tablet formulation makes it possible for patients to be safely dosed at home and would increase the number of patients who could be treated at any one time.” He added that when formulated as an extended-release tablet, taking around 10 hours to release, most of the ketamine is metabolized in the liver. “The low ketamine blood levels mean patients experience few or no side effects.” The study reported the majority of side effects were of a mild or moderate intensity. The most common adverse events included dizziness, headache, dissociation, feeling abnormal, fatigue and nausea.

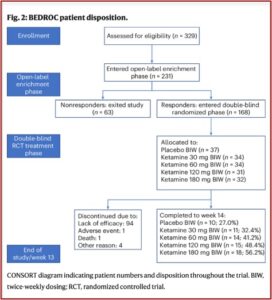

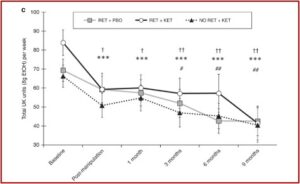

The design of the study eliminated non-responders before randomization in order to reduce the risk of study failure. This meant that of the 231 enrolled in the open-label enrichment phase of the study, (where participants took a daily dose of 120 milligrams of ketamine in the slow-release pill for five days) 63 exited the study as nonresponders and 168 continued as responders. The responders were participants whose MADRS (Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale) score was greater than or equal to 12 and had reduced their scores by at least 50% during the enrichment phase. These responders were then randomized into double-blind groups of four different doses and placebo. See the figure below from the original study.

A CNN Health article on the study reported that experts thought the study was an important first step, but the trial probably biased the results, making the drug look more effective than it would be in the real world. Dr. Gerald Sanacora, who was not involved in the study, said it’s very likely participants knew they were getting ketamine rather than the placebo, and expected it to work. “It is usually easier to guess correctly once you have been exposed to the active treatment and then receive the inactive treatment.” He thought further study in a larger population was necessary. The researchers acknowledged this design likely overestimated response levels, “and future unenriched clinical trials are needed to address this issue.”

Sancora went on to say there was “significant tension” between the potential benefits of ketamine and making sure the treatment can be given safely and responsibly. “This is a step in the right direction, but we clearly need more high-quality data before we can say much more about the overall efficacy and safety of the new form of treatment and especially the safety of doing this at home.” There was also a high dropout rate of the double-blind RCT phase of the study; and one completed suicide.

Of the 168 people who initially saw benefit from the pills, 100 didn’t complete the trial. Ninety-four left because they stopped being helped by their treatment. One person left because of an adverse event. Four others left for unspecified reasons. A 65-year-old man died as a result of suicide.

An independent review committee judged the suicide was a result of the patient’s depression rather than the treatment. Experts agreed it was difficult to know whether the drug played any role in the death, and said larger studies were needed to “tease out” any serious safety issues. “One of the challenges with oral ketamine, one of the reasons that we haven’t used as much for depression as IV, is that it can be sort of unpredictable, and how much is getting into the bloodstream?”

Reflect for a minute on the above reported information. One hundred sixty-eight participants were identified as responders to ketamine treatment for treatment-resistant depression. But 100 (59.5%) didn’t complete the trial; and 94 (55.9%) left because they stopped being helped.

What seems implied, but unspoken here, is that the high dropout rate in the study was fueled by participants recognizing rather quickly that ketamine no longer had an antidepressant effect for them. This suggests two concerns with the study. First, the double-blind part of the open-label enrichment phase was broken, raising the question of the credibility of the supposedly “random” design. Second, the rapid antidepressant effect of ketamine appears to dissipate quickly, raising a concern about the wisdom of ketamine as a long-term treatment for “treatment-resistant” depression. Remember, it is a Schedule III Controlled Substance.

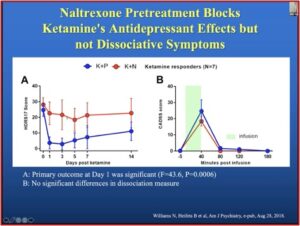

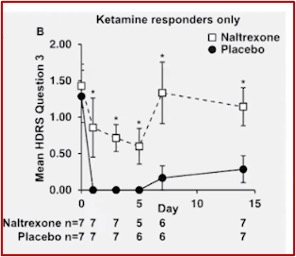

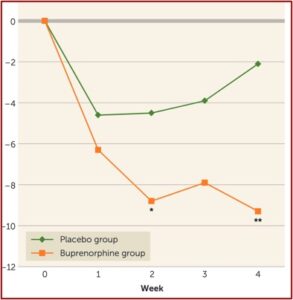

Additionally, there was no significant difference of relief reported between the four treatment phase groups in the study. The CNN article noted while everyone still in the study at 14 weeks reported some relief from their depression, the results when compared with the placebo group were not significant; meaning the reported relief “could have been observed due to chance alone.” So, the antidepressant effect of ketamine could merely a pharmaceutical conjuring trick—now you have it, now you don’t.

See “Evaluating the Risks with Esketamine,” Repeating Past Mistakes with Esketaine,” “Voyages on the Starship Ketamine,” and others for more information on the concerns with ketamine and esketamine to treat depression on my website.