In Search of a Disorder for Ketamine

Interest in getting ketamine approved to treat depression persists, even after the approval of esketamine (Spravato) in March of 2019. The rapid reversal of depression symptoms was first shown with ketamine. But as it was a generic drug, there was no financial motivation for the pharmaceutical industry to invest in its potential. There is still a mystery in knowing exactly how ketamine exerts its effects. Now there is some who theorize it may help with alcoholism.

Soon after the FDA approval of Spravato in 2019, a team of researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine revealed how ketamine induced changes in the brain circuits of mice. Carlos Zarate, who was not involved in the study, said: “It’s a remarkable engineering feat, where they were able to visualize changes in neural circuits over time, corresponding with behavioral effects of ketamine.” He thought the work would help guide what treatments should be doing before they are moved into the clinical setting. The study used cutting-edge technology to visualize and manipulate the brains of stressed mice. Mice subjected to stress display the equivalent of depressed behavior and with antidepressant treatment, they often improve.

In the new study, the researchers used light microscopes to observe tiny structures called spines located on dendrites (a neuron’s “input” wires) in the mPFC [medial prefrontal cortex] of stressed mice. Spines play a key role because they form synapses if they survive for more than a few days.

STAT News said the medial prefrontal cortex is an area of the brain that is thought to be involved in depression. Research has suggested chronic stress can affect the number of synapses in the brain. The Weill Cornell researchers wanted to see if ketamine could reverse those effects. “So they looked at what are known as dendritic spines, tiny projections that shoot off branches of neurons known as dendrites. Most dendritic spines contain functional synapses, so scientists consider them a sign of a connection between two neurons.”

After giving the mice a dose of ketamine, the effects on behavior were rapid. They were more likely to attempt to escape from an unpleasant situation, preferred sugar water over plain water and explored a maze. All three behaviors are indications the mice are not stressed. However, the effects on synapse formation were slower. New synapses did not appear until around 12 hours after a dose of ketamine. This suggested ketamine’s rapid effect was not dependent on the formation of new synapses.

The researchers then used a tool that caused the newly formed synapses to collapse. Within two days, some of the behaviors of the mice reverted back to the behaviors evident during chronic stress. This suggests the new synapses and their continuation are critical to maintaining at least some of ketamine’s effect on behavior.

Zarate noted one limitation of the study was there was only a single dose of ketamine, rather than the multiple doses that occur with human treatment. Might the spines remain after weeks of repeated treatments? “Ongoing effects with repeated administration, we don’t know.” That will be the next question asked in further research.

One caution to remember there is a big difference between stressed mice and depressed humans. Anna Beyler, a neuroscientist of the University of Bordeaux, France, also added: “There’s no real way to measure synaptic plasticity in people, so it’s going to be hard to confirm these findings in humans.” Stay tuned for more mice research.

However, ketamine research is not focused solely on depression. There was a study published in Nature Communications that investigated how maladaptive reward memories (MRMs) are associated with developing and maintaining the overconsumption of alcohol: “Ketamine can reduce harmful drinking by pharmacologically rewriting drinking memories.” The researchers found that a single infusion of ketamine combined with motivational enhancement (MET) counseling can help heavy drinkers curb their drinking. Ninety people who drank an average of four to five pints of beer a day were recruited for the study.

These findings demonstrate MRM reconsolidation interference by ketamine and rewriting of reward structures surrounding alcohol. The subsequent, lasting clinical benefits observed suggest that this one-session intervention approach should be pursued in the future treatment of alcohol related disorders.

The study’s lead researcher, Ravi Das said to Merrit Kennedy of NPR: “When people become addicted, they’re learning that kind of behavior in response to things in their environment.” He added that those memories can be long lasting and become ingrained. “Current treatments don’t target those.” Das and the other researchers thought ketamine might be able to target a heavy drinker’s memories of drinking triggered just before they received a dose of ketamine. The results were said to be a dramatic decrease in the amount of alcohol consumed. “Given the high levels of problematic drinking in the current sample, one may reasonably expect similar effects to be observed in a more severely dependent/treatment-seeking population and there is now a strong rationale to conduct such clinical trials in formally diagnosed populations.”

Peter Simons reviewed the study for Mad in America, “Ketamine for Harmful Drinking: A Look at the Data.” One of the first things he noted was while the article claimed “ketamine can reduce harmful drinking by pharmacologically rewriting drinking memories,” the results were more nuanced and not as positive as presented. “In fact, the group that did not receive ketamine had lower levels of alcohol use throughout the study.” The researchers based their experimentation on a memory-based theory of how problem drug abuse develops. According to the theory, memories of the rewards associated with drug use are triggered when a person sees the drug, which causes them to want more of it.

The theory underlying this study is that ketamine may cause short-term memory loss. But the research did not directly test this idea. Rather, the researchers looked at a broader idea—that a ketamine infusion may reduce problematic drinking.

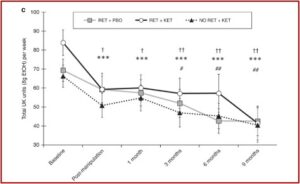

There were three groups in the study. One group received a placebo instead of ketamine and also the alcohol memory task (RET+PBO), another ketamine and alcohol memory task (RET+KET), and the third group had no memory task and ketamine (NO RET +KET). The researchers found that the ketamine infusion and alcohol task group drank far less than their baseline levels. But they also began the study with a significantly higher baseline of drinking than the other two groups. All three groups did better over time and the group that received ketamine and the alcohol task (RET+KET), did worse than the other groups until the nine-month end point of the study, when all three groups were drinking about the same amount of alcohol. The researchers interpreted their findings as meaning that ketamine successfully reduced the amount of alcohol drank by the study’s participants. See the following chart.

However, as Peter Simon noted, “This finding is what would be predicted by chance.”

However, as Peter Simon noted, “This finding is what would be predicted by chance.”

One statistical phenomenon that occurs by chance is called regression to the mean. In that phenomenon, groups that start at an abnormally high (or low) point on any scale are more likely to return to the average over time. For instance, let’s say an event occurs—like a wedding, or a holiday celebration, during which you drink much more than usual. You are most likely to return to your regular drinking amount afterward. And that’s what we see here.

The researchers do acknowledge this possibility, saying in their study, “We cannot rule out regression to the mean as a contributing factor to the observed reduction in alcohol consumption.” Yet they denied that regression to the mean was responsible for their results, calling that commonly occurring statistical phenomenon “highly unlikely.” Asserting the significance of their findings, the researchers said the lasting clinical benefits observed suggested this intervention approach should be pursued in the future treatment of alcohol use disorders.

There is another limitation to the significance of the findings in how they conceived harmful alcohol use. The researches understood problem drinking as fundamentally a learned behavior problem. “Overconsumption disorders such as harmful drinking, alcohol and substance use disorders (AUDs, SUDs), which represent leading causes of global preventable mortality and morbidity, are fundamentally acquired or learned behaviours.” Such a conception of substance use disorders is reductionistic. There is a clear element of learned behavior in the development of a drinking problem, and there is clear evidence of there being a physiological element for many individuals with alcohol use disorders (See “The Genetic Connection”).

Following the thinking of Carleton Erickson in The Science of Addiction, there is a distinction between what earlier editions of the DSM called drug abuse and drug dependence. “According to these criteria, drug abuse is intentional, ‘conscious,’ or voluntary. Drug dependence is pathological and unintended.” Alcohol dependent people have a dysregulation of the mesolimbic dopamine system and typically cannot stop drinking without intensive intervention. There is an overlap between individuals with an alcohol abuse problem and those with an alcohol dependence problem, illustrated by this chart derived from the first edition of The Science of Addiction:

| Alcohol Abuse | Alcohol Dependence | Alcohol-Seeking |

| Mild | Little/None | |

| Moderate | Some | |

| Severe | Mild | A Lot |

| Moderate | Even more | |

| Severe | All the Time |

Alcohol Dependence was a continuous and compulsive pattern of use, often with tolerance and withdrawal symptoms, suggestive of a physical dysregulation. Most alcohol abusers “never become addicted in any meaningful sense.” The abuse/dependence distinction for substance use disorders was part of the DSM diagnostic system before the DSM-5. The DSM-5 collapsed the distinction between abuse and dependence, establishing a continuum of alcohol use disorder instead of two separate disorders of alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence. As a result, the above noted diagnostic distinction between abuse and dependence was lost or became unclear. The ability to discern diagnostically between learned substance problems and substance problems driven by physical dysregulation was muddled in the DSM-5.

Only individuals who were never formally diagnosed with a substance use disorder were included in the study. So, this meant that individuals who were most likely to exhibit symptoms of physical dependence, such as withdrawal, cravings and an inability to limit or control their alcohol use, were excluded from the study. Was the subject pool of participants unintentionally made up of individuals most likely demonstrate the study’s results? Were the individuals in the study heavy drinkers who were not on the way to developing what was called an alcohol dependence disorder? What works with undiagnosed heavy drinkers may not work with individuals who are alcohol dependent, who have a moderate or severe form of alcohol use disorder.

For more information on DSM diagnosis and substance use, see: Misdiagnosing Substance Use. For more information on ketamine, see: Ketamine to the Rescue?, Family Likeness In Depression Drugs? or Psychedelic Depression.