Doublespeak in the Opioid Crisis, Part 1

How did we get to the place where overdose deaths from opioids were five times higher in 2016 than 1999? On average, 115 Americans die every day from an opioid overdose. An estimated 66% of all the drug overdose deaths in 2016 involved an opioid. From 1999 to 2016, more than 630,000 people died from a drug overdose. And there is evidence that a 1980 one-paragraph letter published in the New England Medical Journal was used to get us there.

The above statistics were from a CDC page on opioid overdose called, “Understanding the Epidemic.” The article showed a graphic representation of three waves in the rise in opioid overdose deaths. The first wave began in the 1990s with increase of overdose deaths from prescription opioids. “The second wave began in 2010, with rapid increases in overdose deaths involving heroin.” The third wave began in 2013 and is associated with illicitly manufactured fentanyl.

The letter was co-written by Dr. Hershel Jick, a drug specialist at Boston Medical Center. A Boston Globe article reported that Dr. Jick said his letter only referred to hospital patients getting opioids for a short period of time, not long-term outpatient use. He said: “I’m essentially mortified that that letter to the editor was used as an excuse to do what these drug companies did.” In his book, Pain Killer, Barry Meier noted years after the publication of his 1980 letter Dr. Jick said that he and his coauthor submitted their statistics about opioid use as a letter “because they were not robust enough to merit a study.” He added that nothing could be concluded about the long-term use of opioids from his study.

A team of Canadian researchers demonstrated the connection between Jick’s letter and the opioid epidemic. Their analysis of this connection was published in an editor’s note for the New England Medical Journal: “A 1980 Letter on the Risk of Opioid Addiction.” The original 1980 letter is in an appendix for the June 2017 editor’s note by Juurlink et al. in the NEMJ. It is quoted here in its entirety:

Recently, we examined our current files to determine the incidence of narcotic addiction in 39,946 hospitalized medical patients who were monitored consecutively. Although there were 11,882 patients who received at least one narcotic preparation, there were only four cases of reasonably well-documented addiction in patients who had no history of addiction. The addiction was considered major in only one instance. The drugs implicated were meperidine [Demerol] in two patients, Percodan in one, and hydromorphone in one. We conclude that despite widespread use of narcotic drugs in hospitals, the development of addiction is rare in medical patients with no history of addiction.

Dr. David Juurlink, who led the analysis, was quoted by the Boston Globe as saying: “It’s difficult to overstate the role of this letter. . . . It was the key bit of literature that helped the opiate manufacturers convince front-line doctors that addiction is not a concern.” The NEMJ said its readers should be aware Jick’s letter was heavily and uncritically cited as evidence addiction was rare with opioid therapy. “People have used the letter to suggest that you’re not going to get addicted to opioids if you get them in a hospital setting. We know that not to be true.”

Here’s what Juurlink and his colleagues did. They identified 608 citations of the 1980 letter “and noted a sizable increase after the introduction of OxyContin (a long-acting formulation of oxycodone) in 1995.” Of the articles citing the 1980 letter, 80.8% (491) cited it as “evidence that addiction was rare in patients treated with opioids.” Additionally, 80.8% (491) of the 608 articles did not point out the patients who were described by Jick in his letter were hospitalized at the time they received the prescription. Affirmational citations of the article began to decrease after 2002. See the NEMJ article for a chart illustrating this.

Now let’s look at this trend from another perspective. The Joint Commission (formerly The Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations or JCAHO) published a document titled: “The Joint Commission’s Pain Standards: Origins and Evolution.” In 1990 the President of the American Pain Society wrote an editorial criticizing the lack of improvement in pain assessment and treatment since 1970. He said the failure was because patients didn’t tell their doctors and nurses about their pain, nurses weren’t able to adjust doses, and doctors were reluctant to use opioids. Pain, he said, was often invisible. “Pain relief has been nobody’s job.”

In addition to his recommendations to help “make pain visible,” he emphasized the received wisdom of the day that “therapeutic use of opiate analgesics rarely results in addiction.” This wisdom “was based on only a single publication that lacked detail on how the study was done.” That “study” was the one done by Dr. Hershel Jick and the citation was his 1980 article in the NEMJ. The next year the American Pain Society released quality of assurance standards for the relief of both acute pain and cancer pain. The recommendations followed the previous recommendations of its President. The Joint Commission followed suit and announced new standards for health care organizations to improve pain management in 2000.

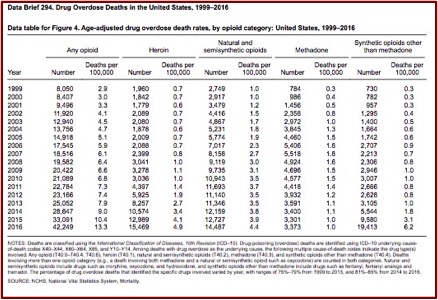

Recall that the CDC marked the beginning of the first wave of overdose deaths as beginning in 1999. In “Understanding the Epidemic” a CDC chart tracked the number of drug overdose deaths since 1999. It noted the initial wave of overdose deaths was due to increased prescribing of opioids (natural and semi-synthetic opioids) beginning in the 1990s; with the second wave of heroin beginning in 2010; and synthetic opioids coming as the third wave in 2016. Below is a CDC data brief apparently used to compile the CDC’s three-wave chart.

The Joint Commission standards were lauded by pain management specialists and called “A rare and important opportunity for widespread and sustainable improvement in how pain is managed in the United States.” However, some raised concerns that the new standards would encourage the inappropriate use of opioids. Total opioid prescriptions had been steadily increasing in the U.S. since 1991, which the Joint Commission attributed to the efforts of advocacy work by pain experts. From 1997 the acceleration for opioid prescribing seems to have become more rapid. “Some of this acceleration in the rate of increase in opioid prescribing may have been due to the 1995 approval of the new sustained-release opioid OxyContin.”

The FDA had approved labeling for OxyContin which said that iatrogenic addiction was “very rare” and that the delayed absorption from the sustained-release formulation in OxyContin “reduced the abuse liability of the drug.” These claims were used by Purdue Pharmaceuticals in marketing campaigns to physicians and in more than 40 national pain-management and speaker training conferences; all expense paid ones, that is. In 2001 the FDA required Purdue to remove these unsubstantiated claims form the OxyContin labeling. But the damage was done. “However, the concept that iatrogenic addiction was rare and that long-acting opioids were less addictive had been greatly reinforced and widely repeated, and studies refuting these claims were not publish until several years later.”

So a one-paragraph 1980 letter became a kind of doublespeak, misused by Purdue Pharmaceuticals and others to change popular and medical thinking about pain management. And the first wave of the opioid epidemic was the result.

Updated with additional information on Dr. Jick’s 1980 letter on 6/8/2018