The Vicious Cycle of Antidepressant Use

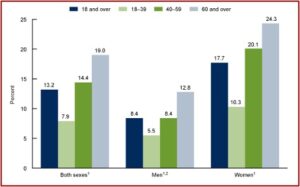

CDC data reported that 13.2% of adults used antidepressants in the past 30 days, and their use increased with age. A similar increase by age was apparent when antidepressant use was examined in both men and women. “In all age groups, antidepressant use was higher among women compared with men.” However, a new study suggested that antidepressant use has very little effect on patients’ health-related quality of life.

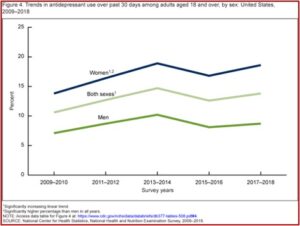

The above information on antidepressant use was taken from the CDC data brief report looking at Antidepressant Use Among Adults in the United States. Antidepressant use in the past thirty days increased among adults aged 18-39 (7.9%), then to 14.4% among adults aged 40-59, and to 19.0% among adults aged 60 and over. Disconcertingly, 20% of women between 40 and 59 almost one quarter of women 60 and over were prescribed antidepressants. Overall, antidepressant use increased from 10.6% in 2009 to 13.8% in 2018. See the following charts from the CDC data brief.

The New York Times cited these statistics in “How Much Do Antidepressants Help, Really?” It observed that clinical drug trials only follow people taking antidepressants for 8 to 12 weeks, missing the vast majority of people who take them longer. The NYT article then referenced a study published in April of 2022, “Antidepressants and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) for patients with depression.” This study compared Americans with a depression diagnosis who took antidepressants, to Americans with a depression diagnosis who did not take the medications over the course of two years.

The data came from the US National Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (MEPS). The study included all types of antidepressants—SSRIs like Prozac, SNRIs like Effexor, and older antidepressants like phenelzine. The researchers found no significant differences in the changes in quality of life reported by the two groups, suggesting “that antidepressant drugs may not improve long-term quality of life.”

A physician and epidemiologist who was not involved in the study said it was difficult to come to a conclusion on this study alone. Individuals who are prescribed antidepressants are likely more depressed than individuals who aren’t prescribed drugs. “People with more severe depression might be less likely to improve their mental quality-of-life scores over time,” for reasons that don’t correspond to the antidepressants they take. When Peter Simons reviewed the study for Mad in America, he said that critique was simply false.

The researchers used a statistical method called the difference-in-difference (D-I-D) analysis that compared each subject’s follow-up levels to their individual baseline levels for their physical and mental component summaries, (PCS and MCS). They acknowledged their study’s inability to control for the effect of the severity of depression. “However, the D-I-D analysis compare each subject’s follow-up levels to his/her individual baseline levels for the PCS and MCS and investigate the overall change for the group which should minimize the impact of this factor on the overall analysis.”

Another perceived issue with the study was that since people were taking antidepressants for an extended time, some quality-of-life improvements could have taken place before the study began following them. Omar Almohammed, a co-author of the study said it was still reasonable to expect continued increases in quality of life long after beginning an antidepressant. “If we don’t expect improvement from the continuous use of these medications, then the correct decision might be to stop the continuous use of these medications.”

But pills are often cheaper. And it can be difficult for some to access therapy because there aren’t enough providers, and mental health treatment aren’t fully covered by all insurance plans. Robert DeRubeis of the University of Pennsylvania said, “It’s not at all clear that even in the short term, pharmacological approaches, on average, are more effective than psychological ones.”

Clinical trials suggest that although antidepressants do improve depression symptoms over the first few months, their benefits are modest and are much less pronounced among people with mild depression compared with those with severe depression. (This is worrying considering that, according to one study, 73 percent of Americans prescribed antidepressants don’t even have a diagnosis of depression.) And experts are divided over whether these small benefits make a noticeable difference to people’s moods or overall functioning.

Much of this improvement is attributed to the placebo effect, rather than the medication itself. Even researchers who argue the benefits from antidepressants admit they “do not work for everybody.” And over time, they will have even less benefits. There are approximately 15.5 million Americans who have been taking antidepressants for at least five years. The longer that people take them, there will likely be increasingly smaller benefits, “in part because patients build up a tolerance to the medications.”

But there is a vicious cycle if you decide to discontinue your use of antidepressants. Too rapid of a taper can lead to antidepressant withdrawal, euphemistically called “discontinuation syndrome.” These withdrawal symptoms are sometimes seen as a depressive relapse, “proving” the need to remain on antidepressants in order to hold off a major depressive episode. They often include physical sensations such as dizziness, nausea, and “brain zaps” (an electric shock sensation in the head). In “Distinguishing relapse from antidepressant withdrawal,” Mark Horowitz and David Taylor said many withdrawal symptoms overlap with symptoms of anxiety or depressions, making it difficult to distinguish.

Their onset soon after dose reduction, the association of psychological with physical symptoms, their prompt response to reinstatement, and their typical ‘wave’ pattern of onset, peak and resolution can help distinguish withdrawal symptoms from relapse.

Giovanni Fava has researched the adverse effects of antidepressants for almost thirty years. In 1994, he said in an editorial for the journal Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, “The field of psychopharmacology has generally neglected the issue of potential sensitization of psychiatric disease to psychotropic drug use.” In January of 2022 he released Discontinuing Antidepressant Medications, as a guide for clinicians who want to help patients withdraw from antidepressants. Fava was interviewed by James Moore about the release of his book for a Mad in America podcast.

In Discontinuing Antidepressant Medications, Fava introduced the construct of behavioral toxicity of psychotropic drugs, applying it to the field of antidepressant tapering and discontinuation. Fava said it was originally described by Alberto DiMascio and Dick Shader.

A medication that is used at the normal, average doses may become toxic to the patient and this toxicity expresses itself with phenomena such as loss of clinical effect, where the patient is doing well on antidepressant and after a while of taking medication regularly, the antidepressant no longer works. If you try to increase the dosage, it may only help for a little while. So, loss of clinical effect and hypomanic episodes—that is the medication is really working too much and brings the patient to a state of hypomania or mania which is a symptom of bipolar disorder—but also a paradoxical fact that is that the antidepressant makes you more depressed.In the book, I discuss the relationship between venlafaxine and apathy. This is an example of a paradoxical effect and resistance, the fact that these patients become resistant either to the same medication, when it’s prescribed again or to another medication. Withdrawal is part of behavioral toxicity and my view is quite different from that of other investigators in the field because as a clinician I know that all these manifestations of behavioral toxicity are related.

Fava said if you have two, or three or even four of these manifestations together, it is likely an example of behavioral toxicity. He works with the most difficult cases and explained that the longer a patient is on a medication, “The higher the toxicity that you provoke.” In other words, the antidepressant that initially was effective “has become toxic” to the patient and is causing a problem. He said it is difficult to discontinue an antidepressant if you don’t use some additional medications and psychotherapy. Discontinuing antidepressants is not something that can be applied to all patients.

So, when I discuss with a patient, I’ll say that most of the patients, 90% of the patients respond, “Please, get this medication out of my body as soon as you can.” Then, we continue with that, but a basic problem which is not only in this field but in psychiatry and in medicine today is to believe that there is a procedure we should apply to all patients, and that is clinical practice shows that it’s not possible.

Antidepressant withdrawal, discontinuation syndrome, is becoming a greater concern in American psychiatry, but it isn’t where it needs to be. In addition to Giovanni Fava, Peter Breggin has been critical of the over prescription of psychiatric medications and wrote Psychiatric Drug Withdrawal in 2013. In 2020, the Royal College of Psychiatrists published “Stopping Antidepressants,” which contains information for “anyone who wants to know more about stopping antidepressants.” In May of 2018, The All-Party Group for Prescribed Drug Dependence (in the Parliament of the U.K.) published, “Antidepressant Dependency and Withdrawal.”

The Executive Summary of that publication said it was incorrect to view antidepressant withdrawal as largely mild, self-limiting and of short duration. Antidepressants fulfill criteria for being dependency-forming medications. Around one-third of users “report being addicted to AD [antidepressants], according to their own definition of that concept.” The increase of long-term antidepressant use along with with the misdiagnosis of withdrawal reactions warrants serious concern.

The lengthening duration of AD use (which has doubled on average in the last 10 years) has fuelled rising AD prescriptions over the same time period. The evidence suggests that such lengthening duration may be partly rooted in the underestimation of the incidence, severity and duration of AD withdrawal reactions; underestimations which may have led to many withdrawal reactions being misdiagnosed as relapse or as failure to respond to treatment. It warrants serious concern that the misdiagnosis of withdrawal may be contributing to escalating long-term AD use (since drugs are being reinstated rather than withdrawn), given that long-term use is associated with increased severe side-effects, increased risk of weight gain, the impairment of patients’ autonomy and resilience (increasing their dependence on medical help), worsening outcomes for some patients, greater relapse rates, and the development of neurodegenerative diseases, such as dementia.

For more on antidepressants on this website, try: “Withdrawal or Relapse When Tapering Antidepressants?” and “Are Antidepressants Worth the Risks?”