Global Concerns with Gabapentinoids

I saw an unexpected market research report on LinkedIn, Gabapentin Market Size in 2024. Unexpected in the sense that I was surprised that a drug that has been a generic medication since 2004 would have a place in the global market in 2024. The Report, more of a teaser to get you to pay $4900 for the full report from Precision Reports, said the global market is anticipated to rise at a considerable rate between 2024 and 2031. Gabapentin was the 6th most prescribed drug of 2021 and the 10th most prescribed drug of 2022. Not bad for a medication referred to once as “the snake oil of the twentieth century” by a Pfizer executive (See “Twentieth Century Snake Oil”).

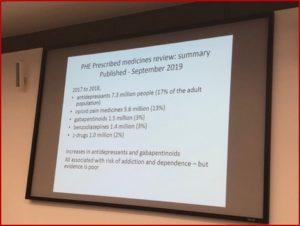

Chan et al evaluated the global trends in gabapentinoid (gabapentin and pregabalin, Neurontin and Lyrica respectively) consumption between 2008-2018 from 65 countries and regions globally and showed there was a 17.20% increase in global consumption. “The study shows that despite differences in healthcare system and culture, a consistent increase in gabapentinoid consumption is observed worldwide, with high-income countries remaining the largest consumers.” Approved indications include neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia, restless legs syndrome, generalized anxiety disorder (not in the U.S.), and others. Given their potential for misuse, the authors said there was a need to understand the global consumption of gabapentinoids.

One of the major factors driving the overall increase in gabapentinoid consumption is their wide range of indications. They suggested the need to revisit the appropriateness of off-label gabapentinoid prescriptions as it seems to be based on clinical experience with mixed or limited evidence. Another reason for the increase of gabapentinoid consumption is they are viewed as a safer alternative than opioids and benzodiazepines. This is despite the risk of misuse with or without their concurrent use with opioids or benzodiazepines. “Patients who have a history of opioid, benzodiazepine, or alcohol misuse have been reported as being vulnerable to misuse gabapentinoids.”

The consumption of gabapentinoids has increased significantly over the span of 11 years, from 2008-2018, inclusive. This increasing trend has been consistent among countries from all income levels. High-income countries remained to be the largest consumers of gabapentinoids, whereas upper-middle-income and lower-middle-income countries showed greater growth in consumption. Against the background of this evidence of increasing use, considering both the abuse potential and the mixed evidence for off-label use, further studies are warranted to investigate the implications behind the increase in consumption and if there is a case for international and national regulatory bodies to review existing treatment guidelines and public health policy relating to gabapentinoids.

Patricia Weiser, PharmD described the similarities and differences of gabapentin and pregabalin. They belong to the same class of drugs known as anticonvulsants or antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). They work by mimicking the effects of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). GABA is thought to have a calming effect and reduce nerve activity in the brain, “which is believed to slow down nerve signal involved in seizures and pain.” Pregabalin is more potent than gabapentin on a per-milligram (mg) basis. She said off-label uses of both include: generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, PTSD, OCD, migraine, bipolar disorder and substance use disorder.

Peet et al noted around 95% of gabapentin prescriptions in the U.S. were for off-label pain management use, despite studies questioning its pain management effectiveness and its misuse with concurrent opioid therapy. In 2006, opioid analgesic episodes plateaued between 50 and 56 million episodes before decreasing to 42.1 million in 2018. Gabapentin episodes increased from 1.5 million in 2006 to 8.1 million in 2018. Concurrent opioid analgesic and gabapentin episodes (OACGs) increased from 1.9% in 2006 to 7.6% in 2018, a relative increase of 344%. Between 2006 and 2018, 18.1% of all OACGs consisted of OA and gabapentin episodes beginning in the same week. See the following figure from the Peet et al study.

Despite gabapentin’s questionable effectiveness in pain management, OACG prescribing has increased, with a potential associated increased risk of all-cause and drug-related hospitalizations. Pain specialists were the most frequent OACG prescribers. Differences between specialties may be exacerbated by cases in which gabapentin may have modest impact (eg, chronic and/or neuropathic pain), by the complexity of cases overall, or because opioid prescribing restrictions more severely affect pain management strategies for complex cases. Prescribing patterns for OACG were similar to those for female patients, patients 66 years or older, and counties with high poverty levels, rural populations, and predominantly non-Hispanic White populations, suggesting that increased OACG prescribing may therefore be an unintentional consequence of opioid prescribing restrictions. Better understanding factors associated with these trends, and to what extent they may be mitigated or exacerbated by prescribing policies and/or physician education, will facilitate efforts to address this increasingly common and potentially dangerous clinical practice. Limitations of this study include observing dispensed not written prescriptions, data limited to retail pharmacies, and lacking information on patient clinical status.

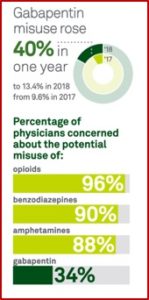

These trends have led to the American Psychiatric Association warning psychiatrists of the risks of prescribing gabapentinoids in “Before You Prescribe Gabapentin, Consider These Risks” in Psychiatric News. Donald Egan noted that while gabapentin was initially marketed as having a low potential for abuse, “a growing body of evidence highlights the potential risks of overprescribing the medication.” Psychiatric News said there were several factors to keep in mind when prescribing gabapentin or with patients who have been prescribed gabapentin by another doctor. In 2004, Pfizer pleaded guilty to multiple counts of illegally promoting the off-label use of gabapentin, which resulted in $430 million in fines.

The increased use of gabapentin with opioids has contributed to a surge of negative health outcomes, including hospitalizations and death. In 2019 the FDA issued a warning about the risks of respiratory depression from gabapentinoids used in combination with CNS depressants such as opioids, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines. Despite the warning, gabapentin prescribing increased. “At least 40% to 65% of individuals with prescriptions for gabapentin and roughly 20% for individuals who misuse opioids report gabapentin misuse.”

Egan suggested gabapentin misuse could be partly driven by dependence and withdrawal symptoms. He said studies have shown that patients who took as little as 400 mg daily for 3 weeks may experience withdrawal symptoms, “including anxiety, pain, nausea, fatigue, and restlessness.” These can begin as soon as 12 hours of stopping, and can last up to 10 days. Implied here is then to taper off of gabapentin and not stop it cold turkey.

In 2022 the CDC published a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), noting the number of overdose deaths involving gabapentin between 2019 and 2020. The CDC report said gabapentin was the 7th most prescribed medication in the U.S., as opposed to the 10th most prescribed medication reported above, with 69 million prescriptions dispensed. While data indicated how gabapentin was associated with intentional abuse, less was known about the drug’s role in fatal overdoses. The CDC analyzed data from the State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System (SUDORS).

The data analysis showed that of the 58,362 deaths, 9.7% (5,687) detected gabapentin in the toxicology results. Of those with a positive gabapentin test, “Gabapentin-involved deaths occurred in 2,975 of 5,687 decedents (52.3%).” The percentage of opioid-involved deaths with gabapentin remained high, ranging from 85% to 90%. “The percentage of deaths that involved a prescription opioid declined from 41.9% of deaths with gabapentin detected in the first quarter of 2019 to 33.0% during the last quarter of 2020.”

During 2019–2020, gabapentin detection and involvement in fatal drug overdoses increased, appearing to follow the rising trend in overall overdose deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic. Overall increases were largely driven by increases in synthetic opioids such as illicitly manufactured fentanyls and likely exacerbated by the social and economic consequences of the pandemic. Nearly 90% of drug overdose deaths in which gabapentin was detected also involved an opioid, particularly (and increasingly) illicitly manufactured fentanyls. Although gabapentin testing is recommended as part of comprehensive postmortem toxicology testing protocols for drug overdose death investigations in the United States, gabapentin is not included in the list of substances recommended in an adequate analyte panel and is not uniformly included on death certificates by some certifiers; therefore, overdose deaths involving gabapentin or with gabapentin detected are likely underestimated. Routine gabapentin testing, as part of comprehensive postmortem toxicology testing protocols for drug overdose death investigations, could further elucidate its role in drug overdose deaths. Despite the lack of uniform testing, gabapentin detection and involvement in overdose deaths increased during 2019–2020. These findings highlight the dangers of polysubstance use, particularly co-use of gabapentin and illicit opioids. Persons who use illicit opioids with gabapentin should be educated about the increased risk for respiratory depression and death.

Egan recommended psychiatrists educate their patients on the risks and benefits of gabapentin use, especially the potential for abuse, dependence and overdose. They should screen patients for substance use disorders and other medications, to reconcile any medications they are taking that could lead to adverse interactions. The effectiveness of gabapentin in treatment should be periodically evaluated and stopped if the desired outcomes are not achieved within six months. Finally, he said adverse events related to gabapentin should be reported. “Such information will contribute to a better understanding of the safety profile of the medication and help regulatory agencies take appropriate measures if needed.”

Amidst the emerging evidence of the adverse consequences of over prescribing of gabapentin, there is a pressing need for medical professionals to discuss the prescribing practices involving these medications. These conversations should focus on evidence-based interventions over unsupported off-label applications that do not have data to support their efficacy and may lead to long-term impacts on health. This is not to say that there is not a role for gabapentin in modern medical practice, but rather a need to reevaluate prescribing practices in order to maximize patient care as well as prevent the potential development of a medication-related crisis.

In The Truth About Drug Companies, Marcia Angell documented how gabapentin (Neurontin) grew from its original approval as a secondary treatment for epilepsy into a blockbuster drug by encouraging doctors to use it to treat common, but vague conditions like pain and anxiety. The problem of drug-related deaths and gabapentin has been a concern since at least 2022 when Public Citizen filed a petition with the FDA and DEA to make gabapentin a federally controlled substance, requesting it be placed as a Schedule V drug, where pregabalin (Lyrica) is scheduled. There has been no federal action yet, despite the increase of deaths associated with both drugs. The petition noted that for each increase of 100,000 gabapentinoid prescriptions, the number of deaths increase by approximately 5% (See Exhibit 5 for a graph representating this increase). While both gabapentin and pregabalin are scheduled as controlled substances in the United Kingdom, the U.S. has yet to do so with gabapentin.