Ability to Choose … Within Limits

It’s not too difficult to discover where Sam Harris stands on whether or not humans have free will. We unequivocally don’t. “Free will is an illusion.” In a lecture Harris gave for Skeptic Magazine that was based on his book, Free Will, he added that if the scientific community were to publically declare free will to be an illusion, “it would precipitate a culture war.” Science has revealed that we are “biochemical puppets” and “The universe is pulling your strings.”

Free will is an illusion. Our wills are simple not of our own making. Thoughts and intentions emerge from background causes of which we are unaware and over which we exert no conscious control. We do not have the freedom we think we have.

This illusion of free will is based on two false assumptions, according to Harris. The first is that we can behave differently than we did in the past. But since we live in a world of cause and effect, our wills are determined by a long chain of prior causes, “and we’re not responsible for them.” Alternately, what we perceive as free will is the product of chance; and again, we’re not responsible. Or there could be some combination of chance and cause and effect, but still no personal agency. Whichever way we conceive it, free will is an illusion in a world ruled by chance and cause and effect.

The second false assumption is that we are the conscious source of our thoughts and actions. “We presume an authorship over our own thoughts and actions that is illusory.” There is no self, no ego, no soul to generate thoughts and actions, according to Harris. They just emerge in our consciousness. And if we cannot control our thoughts, if we don’t know what our next thought will be until it consciously emerges, where is our free will?

How can we be free as conscious agents, if everything we consciously intend was caused by events in our brain, which we did not intend, and over which we had no control?

Sam Harris is an author, philosopher and neuroscientist who has written several popular books in addition to Free Will. Along with Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett and Christopher Hitchens, he has been referred to as one of the “Four Horsemen of New Atheism.” The reference draws on the title of a 2-hour unmoderated discussion between the four that is available here on the website for the Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science. They discussed the public reaction to some of their books critical of religion, and some common misrepresentations of them and their beliefs.

Harris’s position on free will assumes the universe is a closed system of cause and effect. Since there are no creator gods, everything that now exists is the result of what has come from “a long chain of prior causes.” The theologian Francis Schaeffer referred to the understanding of science that comes from this view of the universe as modern, modern science—science rooted in naturalistic philosophy. The uniformity of natural causes, which is an essential starting point for scientific investigation, must be understood as occurring entirely within the natural order of the universe. Nature is closed to any causal intervention from outside.

There is no Creator; no First Cause. There is only chance or cause and effect. Not only physics, but psychology, social science and human nature must be explained within the confines of this closed system. The biologist and neuroscientist Robert Sapolsky believes that every bit of human behavior has multiple layers of causality. He said what we call “free will” is simply biology that hasn’t been discovered yet. “It’s just another way of stating that we’re biological organisms determined by the physical laws of the universe.” See “Ruling Over Our Genes” for more on Sapolsky.

In Escape From Reason, Schaeffer concluded this materialist unity of all things leaves us afloat on a deterministic sea with no shore. The only way this unity can be achieved is by ruling out freedom. “The result of seeking for a unity on the basis of the uniformity of natural causes in a closed system is that freedom does not exist.” Free will is therefore an illusory cognitive construct. The nonmaterial mind or soul is also an illusion.

However, Harris and Sapolsky aren’t the only neuroscientists to ever consider the possibility of free will. Harvey McMahon is a staff scientist and group leader at the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge. He is also a member of The Royal Society, the world’s oldest independent scientific academy. Past members of the Society have included Isaac Newton, Albert Einstein and Charles Darwin. Current members include Richard Dawkins and Stephen Hawking.

McMahon discussed free will in: “How Free Is Our Free-Will?” He opened his essay by noting science has provided evidence that free-will may be an illusion. Yet free-will was fundamental to our sense of wellbeing, and underwrote our sense of morality, our judicial system, and our Judeo-Christian faith. “We may not be as free as we would like to think, but within boundaries shaped by our individual histories, our genetics, and our environment we can make decisions that determine our character, relationships and future.”

He noted the paradoxical nature of freedom. For example, if we marry we limit the relationships we will have with others, while at the same time opening up new avenues of freedom from being settled in our choice of partner. This principle, McMahon said, applies to all our choices. We change our future possibilities by the choices we make today. “Thus freedom is not unconstrained choice, for with each choice we limit our freedom, and in so doing shape our environment and ourselves.”

These constraints are from our culture, our relationships, our jobs and our families, and other influences. Added to these is the subconscious working of our brain, processing cues of which we are not aware. “Thus the brain may even be making decisions for us.” Do we really have a choice? Here McMahon acknowledged Harris’ above noted argument (and book), that free-will was an illusion. But rather than an illusion, he thought it better to say it was constrained by many factors.

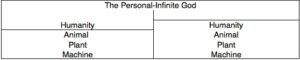

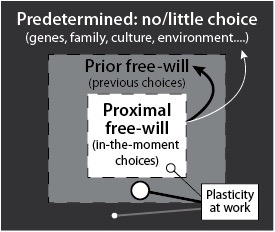

Free-will, McMahon thought, “is a cognitive concept, involving the mind.” It is the ability to choose deliberately between options. “It cannot be regarded as the opposite of determinism, where events have cause and effect outside human control.” He illustrated what he meant with the following diagram. Free-will only applied to cognitive processes where we use our minds to make choices—in between the two extremes. Although not stated by McMahon, I’d say completely free choice is only possible within the mind of God.

Human free-will is then not completely determined, nor is it completely free. McMahon suggested free-will occurred within the boundaries of predetermined factors, where there was little or no freedom to choose. These factors could be biological or genetic. They could also be family, culture, or environmental factors. See the diagram below.

Within an outer sphere of predetermined boundaries, lies a continuum of interaction between prior free-will and proximal free-will. Prior free-will is where an immediate decision is constrained by past decisions and history. Going to work on a given day is more the result of a past decision than one made when you woke up that day. You can re-assess the decision and not go to work for some reason, “yet the choice does not have to be constantly re-evaluated.” In-the-moment or proximal decisions can be inconsequential, like choosing between tea or coffee, or involve active cognition, as when we weigh our options. “Both of these give a strong sense of free-will in the moment.”

Plasticity refers to the fact that our brains are moldable. “We are constantly learning new information, meeting new people and acquiring new skills, which all require that our brains are ‘plastic’.” New synapses can be formed or existing synapses can be modified or lost. “At a molecular level there can be changes in the expression of various proteins which in turn influence the excitability of a given synapse or circuit.”

Plasticity refers to the fact that our brains are moldable. “We are constantly learning new information, meeting new people and acquiring new skills, which all require that our brains are ‘plastic’.” New synapses can be formed or existing synapses can be modified or lost. “At a molecular level there can be changes in the expression of various proteins which in turn influence the excitability of a given synapse or circuit.”

The choices we make influence the behavior patterns we develop, which are laid down as neuronal pathways. In turn, these pathways influence other choices. “So in this sense we are masters of our own destiny… all because we have a ‘plastic’ brain (i.e. not completely preprogrammed).” Although there is difficulty in the process, we can change. If we make certain choices repetitively, they lay down neuronal pathways and turn into learned behaviors.

Plasticity is thus key to the possibility of free-will [see the above diagram]. While memories of past experiences may not be completely eradicated, they can be scaled back by the new experiences that occupy our minds as we choose to dwell on other things.

Jeffery Schwartz and Rebecca Gladding coauthored You Are Not Your Brain, a self-help book that applies the principles of neuroplasticity discussed above. Like McMahon, Schwartz and Gladding affirm the reality of the human mind and the existence of free-will. Dr. Schwartz is one of the world’s leading experts in neuroplasticity. You can read more about him and his books on his web page here.

McMahon said the relationship between this conception of free-will and intentionality is complex. To the extent we willfully choose and can foresee certain outcomes, ”we can be held responsible for the outcome.” However, if we could not foresee the potential consequences of decisions, to what extent can we say their outcome was intentional? Furthermore, what about when reason has been suppressed for some reason, or if it has been erroneously applied (if we haven’t reasonably weighed our potential thoughts or actions), and non-intended consequences result.

Despite the caveats, in general each of us is responsible today for what we did yesterday because these were acts of free-will, or actions resulting from an absence of self-control. The responsibility for evil can be lessened by considering our circumstances but it never excuses us because at some point in the past we have actively participated in shaping who we are today.

McMahon goes on to describe how he believes our brains and free-will interact with each other. He suggested that while individual neurons do not have free-will, “it is an emergent property of neuronal networks.” He suggested free-will sits upon a tripod of past memories, present inputs (combined with the ability to compute and learn) and future predictions and aspirations within the plasticity of the brain.

There is more to read and think about in his article. McMahon also shares his thoughts on how God constrains us and yet frees us. He wrestles with the question of whether free-will is compatible with divine sovereignty. Read more on how he applies the above discussion to this theological dilemma. His conclusions are worth repeating here.

With the above in mind the following definition of free-will can be offered: Free-will is the ability to choose intentionally within limits placed by a sovereign God, with resulting human responsibility. Free-will is not the opposite of determinism: one can have free-will within the limits set by determinism. Indeed our relationships and our decisions are not absolutely predetermined, and this is a reflection of the freedom given to us by being made in the image of God. So, we have the best of both worlds, where we have freedom to make decisions and yet our personal future and that of the world are secure.

The above understanding of free-will indicates we are less free than we may like to think we are at any given moment, because of prior decisions and predetermined factors. And while neuroscience hasn’t extinguished free-will, it does help us see why we do the things we do. So we are not biochemical puppets, but biology constrains us. “We are not determined by our past, but certainly influenced by it.”