The Unique Scientific Value of Ibogaine Part 3

In a March 6, 2019 interview with The New York Times, Gwyneth Paltrow was asked what the next big thing Goop would be plugging, and she responded: “I think how psychedelics affect health and mental health and addiction will come more into the mainstream.” At the time, she confessed she had never used psychedelics and was terrified at the process. And yet, she acknowledged there seemed to be a link between a psychedelic state and being connected to “some other universal cosmic something.” She then mentioned ibogaine, a hallucinogen being promoted as a treatment for addictions. The interviewer asked if ibogaine would be the next big thing she would read about on Goop, and Gwyneth back-pedaled, saying she didn’t know. Then “The Healing Trip,” appeared as the first episode for the Netflix series, The Goop Lab, where several Goop employees went to Jamaica to ingest magic mushrooms.

The New York Times referred to this as “Goop-ification,” when Gwyneth Paltrow’s health and beauty company, Goop, regularly wrote articles on the health benefits of hallucinogens. The Times article highlighted three authors. Michael Pollan, who wrote the best selling How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression and Transcendence, chronicled the history of psychedelic drugs, including his own personal use of psychedelics. There was a memoir, A Really Good Day, written by Aylet Waldman, and a novel about Timothy Leary, Outside Looking In, by T.C. Boyle.

Psychedelics have entered into mainstream conversations, with psychedelics being touted for wellness, lifehacking, therapy and self-care. The Milken Conference, a business event, had a panel called “Psychedelics: Mind-Enhancing Methods to Well-Being.” Silicon Valley entrepreneurs are using Ecstasy, LSD, and magic mushrooms. “A booming—and unregulated—shaman market has emerged.” Ironically, Pollan and Waldman, who published books on the benefits of psychedelics “worry about the ayahuasca retreat gentrification even as they usher more people in the door.” The promises made for what psychedelics can do for you harken back to the days of patent medicines.

But Pollan cautioned against legalizing psychedelics: “Psilocybin has a lot of potential as medicine, but we don’t know enough about it yet to legalize it.” Someone, he feared, could commit suicide while they were coming off of SSRIs in conjunction to their hallucinogenic therapy. “I do think we could have another backlash.” Goop urged caution as well:

If we’ve learned anything from interviewing psychiatrists and psychedelic researchers over the past few years, it’s two things: 1) Psychedelics have incredible potential as therapeutic agents, and 2) they are not something you should approach lightly—they require a great deal of care and expertise and support to have those desired therapeutic effects. They can leave you vulnerable and have the potential for serious (and in rare cases fatal) harm. If you’re considering any experimental healing experience, you should consult your own medical team and understand the risks before proceeding. And for anything involving psychedelics, verify the legal status, as psychedelics are illegal in many countries and unregulated in others.

This psychedelic “renaissance” was explored by Michael Pollan in his 2018 book, How to Change Your Mind. Pollan noted how Western science and modern drug testing depended on the ability to isolate one single variable. Yet it is not clear how the effects of a psychedelic drug can ever be isolated as a single variable from the context in which it is administered—the presence of the therapists involved, or the expectations of the person ingesting the psychedelic. “Any of these factors can muddy the waters of causality.” He then asked how was Western medicine to evaluate a psychiatric drug that appears to work by administering a certain kind of experience in the minds of the person, and not strictly by means of any pharmacological effect?

This is why it is important to understand that “psychedelic therapy” is not simply treatment with a psychedelic drug but rather a form of “psychedelic-assisted therapy,” as many of the researchers take pains to emphasize.

One of those researchers is Dr. Kenneth Alper, who has coauthored multiple papers with Howard Lotsof (See Part 1 for more about Howard Lotsof) and is the first editor of an English language text on ibogaine. In “Ibogaine: A review,” an article in The Alkaloids Chemistry and Biology, February 2001, he said there were “stages” or phases to the subjective experience of ibogaine. He said ibogaine was typically given in a nonhospital setting as a single dose in the morning. Vomiting is common, as it seems to be with the ingestion of ayahuasca, another psychedelic alleged to be helpful in treating addictions. Patients generally lie still in a quiet, darkened room throughout their treatment.

The subjective effects of the Acute phase appear to have common elements described by individuals treated with ibogaine. The onset of the acute phase occurs within 1 to 3 hours of ingesting ibogaine and lasts about 4 to 8 hours. The predominant experiences reported seem to involve “visions” or “waking dreams” of long-term memories. Descriptions from individuals in this state are more consistent with an experience of dreams, rather than hallucinations. Subjects also emphasize their experience of being placed in, or entering/exiting visual landscapes, rather than an intrusive visual or auditory hallucination.

Ibogaine-related visual experiences are reported to be strongly associated with eye closure and suppressed by eye opening. The term “oneiric” (Greek, oneiros, dream) has been preferred to the term “hallucinogenic” in describing the subjective experience of the acute state. Not all subjects experience visual phenomena from ibogaine, which may be related to dose, bioavailability, and interindividual variation.

The Evaluative phase comes about 4 to 8 hours after ingestion, and lasts 8 to 20 hours. The volume of material recalled in the waking visions slows. The emotional tone is described as neutral or reflective. Attention still has an inner subjective focus directed at evaluating the experiences of the Acute phase, rather than the external environment. “Patients in this and the acute phase above are apparently easily distracted and annoyed by ambient environmental stimuli and prefer as little environmental sensory stimulation as possible in order to maintain an attentional focus on inner experience.”

Twelve to 24 hours after ingestion of ibogaine marks the beginning of the Residual Stimulation phase. It lasts somewhere between 24 and 72 hours; maybe longer. There is a return to normal attention to the person’s external environment. “The intensity of the subjective psychoactive experience lessens, with mild residual subjective arousal or vigilance.” Some people report a reduced need for sleep for several days up to a few weeks following treatment. In summary, Alper concluded:

The available evidence suggests that ibogaine and the iboga alkaloids may have efficacy in addiction on the basis of mechanisms that are not yet known and which can possibly be dissociated from toxic effects, and may present significant promise as a paradigm for the study and development of pharmacotherapy for addiction.

Despite the carefully described observations noted here, Pollan still urged caution with psychedelic therapy: “None of these psychedelic therapies have yet proven themselves to work in large populations; what successes have been reported should be taken as promising signals standing out from the noise of data, rather than definitive proofs of cure.” But he didn’t stop there with his investigation into psychedelic therapies.

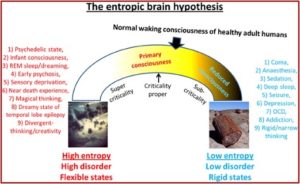

He turned to the work of Robin Carhart-Harris and his theory of the entropic brain. He said it represented a first stab at a unified theory of mental illness and helped explain several psychiatric disorders. According to Pollan, Carhart-Harris believes that “depression, anxiety, obsession, and the cravings of addiction are how it feels to have a brain that has become excessively rigid or fixed in its pathways and linkages.” These disorders are manifested in a brain with more order than is good for it. “On the spectrum he lays out (in his entropic article) ranging from excessive order to excessive entropy, depression, addiction, and disorders of obsession all fall on the too-much-order end.”

In “The entropic brain” article, Robin Carhart-Harris et al proposed a theory of consciousness they called the entropic brain hypothesis. This hypothesis proposes that the quality of any conscious state depends on the system’s entropy measured vie key parameters of brain function. Increased subjective uncertainty accompanies states of increased system entropy. Psychedelics work therapeutically “by dismantling reinforced patterns of negative thought and behavior by breaking down the stable spatiotemporal patterns of brain activity upon which they rest.” Pollan thought this effect, which he called “the dissolution of the ego,” was the most important and therapeutic of all the phenomenological effects people who are on psychedelics report. See the graphic below from “The entropic brain.”

In particular, the changes in activity and connectivity in the default mode network on psychedelics suggest it may be possible to link the felt experience of certain types of mental suffering with something observable—and alterable—in the brain. If the default mode network does what neuroscientists think it does, then an intervention that targets that network has the potential to help relieve several forms of mental illness, including the handful of disorders psychedelic researchers have trialed so far.

In particular, the changes in activity and connectivity in the default mode network on psychedelics suggest it may be possible to link the felt experience of certain types of mental suffering with something observable—and alterable—in the brain. If the default mode network does what neuroscientists think it does, then an intervention that targets that network has the potential to help relieve several forms of mental illness, including the handful of disorders psychedelic researchers have trialed so far.

Pollan said the default mode network (DMN) is a set of interacting brain structures first described by the Washington University neuroscientist Marcus Raichle. It is most active when the brain is in a resting state, linking parts of the cerebral cortex with deeper, older structures of the brain involved in memory and emotion. “Its key structures include, and link, the posterior cingulate cortex, the medial prefrontal cortex, and the hippocampus.”

Neuroimaging studies suggest that the DMN is involved in such higher-order “metacognitive” activities as self-reflection, mental projection, time travel, and theory of mind—the ability to attribute mental states to others. Activity in the DMN falls during the psychedelic experiences, and when it falls most precipitously volunteers often report a dissolution of their sense of self.

The approval of psychedelic therapy with ibogaine has some serious concerns to overcome, but there is enough evidence available to support doing further research and for the FDA to provide the funds for it. However, Michael Pollan may have the right of it in saying, “it isn’t clear that the effects of a psychedelic drug can ever be isolated … from the context in which it is administered.” Deborah Mash’s attempts to somehow separate the drug effect from the set and setting of the dream-like experience of ibogaine may radically, and negatively, effect its efficacy. Her efforts points to the limitations of scientific inquiry into the healing properties of hallucinogens. The Dalai Lama said: “The view that all mental processes are necessarily physical processes is a metaphysical assumption, not a scientific fact. I feel that, in the spirit of scientific inquiry, it is critical that we allow the question to remain open, and not conflate our assumptions with empirical fact.” In closing, Robin Carhart-Harris’s thoughts on the unique scientific value of psychedelics have relevance:

The unique scientific value of psychedelics rests in their capacity to make consciously accessible that which is latent in the mind. This paper takes the position that mainstream psychology and psychiatry have underappreciated the depth of the human mind by neglecting schools of thought that posit the existence an unconscious mind. Indeed, psychedelics’ greatest value may be as a remedy for ignorance of the unconscious mind.