Rewiring the Adolescent Brain with Antidepressants

Research has shown that the earlier in life a person begins to use drugs, the more likely they are to develop serous problems as they mature. The interaction of early social and biological risk factors needs to be considered in assessing the developmental progression of later in life problems like addiction. “The fact remains that early use is a strong indicator of problems ahead, including addiction.” While this is a noncontroversial perspective on how recreational drug use effects adolescent brain development, what about the effects of antidepressants and other psychiatric drugs on the developing brains of adolescents?

As our brains develop, our experiences reduce excess neural connections while simultaneously strengthening those that are used more often. The more we repeat any thinking or behavior pattern, the more it becomes habitually entrenched. If we repeatedly have a specific thinking pattern or do a particular behavior over and over again, the neurons in our brains strengthen that learning sequence, becoming what we refer to as a habit. “The more we actually do of whatever we do, the more ‘habitual’ that learning will become.” This is known as Hebbs Law, “Neurons that fire together, wire together.” When you combine Hebb’s Law with early drug use and the still maturing adolescent brain, you have a ready-made recipe for disaster.

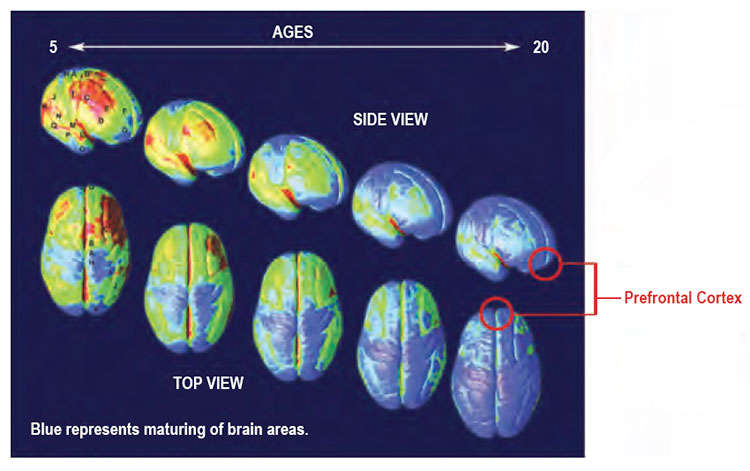

The above images of brain development are found in the NIDA (National Institute on Drug Abuse) discussion of “Drug Use and Addiction.” The images are for normal children and teens from the age of 5 to 20. Scientists think the process of brain maturation, depicted as the yellow to blue transition, corresponds to the steady reduction in gray matter volume seen during adolescence. Note that the pre-frontal cortex is the last area of the developing brain to mature. Environmental forces, like drug use, help determine which connections wither and which are reinforced. This is a process that can “cut both ways” as not every habit reinforced by Hebb’s Law is desirable.

One of the brain areas still maturing during adolescence is the prefrontal cortex—the part of the brain that allows people to assess situations, make sound decisions, and keep emotions and desires under control. The fact that this critical part of a teen’s brain is still a work in progress puts them at increased risk for making poor decisions, such as trying drugs or continuing to take them. Introducing drugs during this period of development may cause brain changes that have profound and long-lasting consequences.

There is a euphoric effect from drugs that is still poorly understood, but it seems to be related to surges of neurotransmitters in parts of the brain’s reward circuit (i.e., the basal ganglia and amygdala). Some drugs cause a surge of neurotransmitters that are significantly greater than the normally occurring bursts produced naturally with healthy pleasurable activities such as eating, or social interaction. “Just as drugs produce intense euphoria, they also produce much larger surges of dopamine, powerfully reinforcing the connection between consumption of the drug, the resulting pleasure, and all the external cues linked to the experience.” Simply put, surges of dopamine “teach” the brain to seek drugs at the expense of other goals and activities.

For the brain, the difference between normal rewards and drug rewards can be likened to the difference between someone whispering into your ear and someone shouting into a microphone. Just as we turn down the volume on a radio that is too loud, the brain of someone who misuses drugs adjusts by producing fewer neurotransmitters in the reward circuit, or by reducing the number of receptors that can receive signals. As a result, the person’s ability to experience pleasure from naturally rewarding (i.e., reinforcing) activities is also reduced.

One of the brain’s areas within its pleasure or reward center is the amygdala, which regulates emotions such as anxiety and depression, as well as having a role in the development of recreational drug addiction discussed above. While antidepressants won’t “shout” at the reward center in the same way cocaine or alcohol does, the individual who uses an antidepressant will experience a similar, if less radical, adjustment of their neurotransmitters and/or receptors. Consider what this could mean in the developing brain of an adolescent using an antidepressant that inhibits the uptake of serotonin (SSRI) or serotonin and norepinephrine (SNRI).

I have no training in medicine or neuroscience. But it seems logical to infer from the above that the long-term use or abuse of any drug which influences the neurotransmitter and/or receptor balance of the brain—cocaine, alcohol, antidepressants or other psychiatric medications—will influence brain function in the way described above. If studies show that “long-term drug use impairs brain functioning,” which the NIDA article claimed, this is equally true for recreational or psychiatric drugs. The question is, to what extent does the use of psychiatric medications like antidepressants effect the development of the adolescent brain?

A study by Lugo-Candelas et al. published in JAMA Pediatrics looked at the association between fetal brain development and prenatal exposure to SSRIs. Their findings suggested there was an association between prenatal SSRI exposure and fetal brain development, “particularly in brain regions critical to emotional processing.” The researchers said there was a need for “further research on the potential long-term behavioral and psychological outcomes of these neurodevelopmental changes.” In her review of the Lugo-Candelas et al. study for Mad in America, Bernalyn Ruiz said: “Overall, this study presents evidence that prenatal exposure to SSRI’s can affect infant neurodevelopment and may be associated with increased susceptibility to anxiety disorders, hyperactivity and maladaptive processing.”

A 2016 study by Cipriani et al. published in The Lancet concluded that the risk-benefit profile of antidepressant use in the acute treatment of major depression with children and adolescents did not seem to offer a clear advantage. The researchers said that fluoxetine (Prozac) was probably the best pharmacological treatment option. The study did not look at long-term antidepressant use as there has not been enough previous research to analyze, according to Cipriani. A STAT News review of the Cipriani et al. study quoted child psychiatrist Jon Jureidini as saying the study’s evidence for Prozac’s effectiveness was weak. He said the vast majority of children do not need to be medicated for depression.

What we’re up against is the marketing enterprise of the pharmaceutical industry combined with wishful thinking on the part of doctors and parents that there might be a good, simple solution for adolescent distress. . . . It’s something we need to take very seriously, but we don’t need to make it into a medical condition when it most times isn’t.

David Healy, Joanna Le Noury and Jon Jureidini wrote about their review of the benefits and risks of the use of antidepressants in children and adolescents for the International Journal of Risk & Safety in Medicine. They examined a total of 20 pediatric antidepressant studies conducted since 1990 and classified them as positive or negative according to the studies’ primary outcomes. In a review of the Healy, Le Noury and Jureidini study for Mad in America, Rebecca Troeger noted the authors found that all 20 trials performed between 1990 and 2005 were negative on primary outcome measures. That included the two fluoxetine (Prozac) trials “that provided the foundation for the drug’s regulatory approval” for use with children and adolescents. There was also evidence of an “excess of suicidality on active treatment” with these trials. “Of the 15 studies conducted since 2006 reviewed by the authors, nearly all were negative on primary outcome measures.”

At a global health conference in Aberdeen Scotland, Dr. Healy said every one of these trials produced more harms than benefits. Children became suicidal who would not have been suicidal if they had been kept off of antidepressants. He said if you follow the evidence, no one should be using these drugs. “At the same time, in teenagers, these drugs have become the most commonly used drugs.” The available evidence seems to question the wisdom and effectiveness of antidepressant use with children and adolescents.