In the Dark About Antidepressants

In 2011, antidepressants were the third most commonly prescribed medication class in the U.S. Mojtabai and Olfson noted in their 2011 article for the journal Health Affairs that much of the growth in the use of antidepressants was driven by a “substantial increase in antidepressant prescriptions by nonpsychiatric providers without an accompanying psychiatric diagnosis.” They added how the growing use of antidepressants in primary care raised questions “about the appropriateness of their use.” Despite this concern, antidepressant prescriptions continued to rise. By 2016, they were the second most prescribed class of medications, according to data from IMS Health.

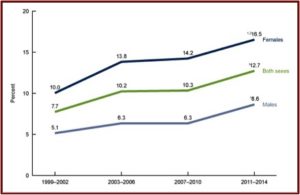

A CDC Data Brief from August of 2017 reported on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. The Data Brief provided the most recent estimates of antidepressant use in the U.S. for noninstitutionalized individuals over the age of 12. As indicated above, there was clear evidence of increased antidepressants use from 1999 to 2014. 12.7% of persons 12 and over (one out of eight) reported using antidepressant medication in the past month. “One-fourth of persons who took antidepressant medication had done so for 10 years or more.”

Women were twice as likely to take antidepressants. And use increased with age, from 3.4% among persons aged 12-19 to 19.1% among persons 60 and over. See the following figures from the CDC Data Brief. The first figure notes the increased use of antidepressants among persons aged 12 and over between 1999 and 2014. You can see where women were twice as likely to take antidepressants as men.

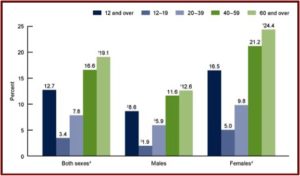

The second figure shows the percent of individuals aged 12 and over who took antidepressant medication in the past month between 2011 and 2014. Note how the percentages increase by age groups for both men and women, with the highest percentages of past month use for adults 60 and over for both men and women.

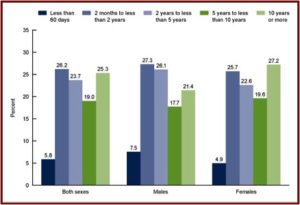

The third figure shows the length of antidepressant use among persons aged 12 and over. Note that while 27.2% reported using them 10 years or more, 68% reported using antidepressants for 2 years or more. “Long-term antidepressant use was common.” Over the fifteen-year time frame of the data, antidepressant use increased 65%.

The widespread use of antidepressants documented above is troubling when additional information about antidepressants is considered. A February 2017 meta-analysis done by Jakobsen et al., and published in the journal BMC Psychiatry, found all 131 randomised placebo-controlled trials “had a high risk of bias.” There was a statistically significant decrease of depressive symptoms as measured by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), but the effect was below the predefined threshold for clinical significance of 3 HDRS points. Other studies have indicated that differences of less than 3 points on the HDRS are not clinically observable. See “Antidepressant Scapegoat” for more information on the HDRS. Jakobsen et al. concluded:

SSRIs might have statistically significant effects on depressive symptoms, but all trials were at high risk of bias and the clinical significance seems questionable. SSRIs significantly increase the risk of both serious and non-serious adverse events. The potential small beneficial effects seem to be outweighed by harmful effects.

In his review of the Jakobsen et al. study for Mad in America, Peter Simons noted where these results add to a growing body of literature “questioning the efficacy of antidepressant medications.” He pointed to additional studies noting the minimal or nonexistent benefit in patients with mild or moderate depression; the adverse effects of antidepressant medications; the potential for antidepressant treatment to potentially worsen outcomes. He concluded:

Even in the best-case scenario, the evidence suggests that improvements in depression due to SSRI use are not detectable in the real world. Given the high risk of biased study design, publication bias, and concerns about the validity of the rating scales, the evidence suggests that the effects of SSRIs are even more limited. According to this growing body of research, antidepressant medications may be no better than sugar pills—and they have far more dangerous side effects.

Peter Gøtzsche, a Danish physician and medical researcher who co-founded the Cochrane Collaboration, wrote an article describing how “Antidepressants Increase the Risk of Suicide and Violence at All Ages.” He said that while drug companies warn that antidepressants can increase the risk of suicide in children and adolescents, it is more difficult to know what that risk is for adults. That is because there has been repeated underreporting and even fraud in reporting suicides, suicide attempts and suicidal thoughts in placebo-controlled trials. He added that the FDA has contributed to the problem by downplaying the concerns, choosing to trust the drug companies and suppressing important information.

He pointed out a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials from 2006 where the FDA reported five suicides in 52,960 patients (one per 10,000). See Table 9 of the 2006 report. Yet the individual responsible for the FDA’s meta-analysis had published a paper five years earlier using FDA data where he reported 22 suicides in 22,062 patients (which is 10 per 10,000). Additionally, Gøtzsche found there were four times as many suicides on antidepressants as on placebo in the 2001 study.

In “Precursors to Suicidality and Violence in Antidepressants” Gøtzsche co-authored a systematic review of placebo-controlled trials in healthy adults. The study showed that “antidepressants double the occurrence of events that can lead to suicide and violence.” Maund et al. (where he was again a co-author) demonstrated that the risk of suicide and violence was 4 to 5 times greater in women with stress incontinence who were treated with duloxetine (Cymbalta).

Although the drug industry, our drug regulators and leading psychiatrists have done what they could to obscure these facts, it can no longer be doubted that antidepressants are dangerous and can cause suicide and homicide at any age. Antidepressants have many other important harms and their clinical benefit is doubtful. Therefore, my conclusion is that they shouldn’t be used at all. It is particularly absurd to use drugs for depression that increase the risk of suicide when we know that psychotherapy decreases the risk of suicide. . . . We should do our utmost to avoid putting people on antidepressant drugs and to help those who are already on them to stop by slowly tapering them off under close supervision. People with depression should get psychotherapy and psychosocial support, not drugs.

Peter Breggin described “How FDA Avoided Finding Adult Antidepressant Suicidality.” Quoting the FDA report of the 2006 hearings, he noted where the FDA permitted the drug companies to search their own data for “various suicide-related text strings.” Because of the large number of subjects in the adult analysis, the FDA did not—repeat, DID NOT—oversee or otherwise verify the process. “This is in contrast to the pediatric suicidality analysis in which the FDA was actively involved in the adjudication.” Breggin added that the FDA did not require a uniform method of analysis by each drug company and an independent evaluator as required with the pediatric sample.

Vera Sharav, “a fierce critic of medical establishment,” the founder and president of the Alliance for Human Research Protection (AHRP), testified at the 2006 hearing. She reminded the Advisory Committee that the FDA was repeating a mistake they had made in the past. She said in the past the FDA withheld evidence of suicides from the Advisory Committee. German documents and the FDA’s own safety review showed an increased risk of suicides in Prozac. “Confirmatory evidence from Pfizer and Glaxo were withheld from the Committee.” Agency officials “obscured the scientific evidence with assurances.”

What the FDA presented to you is a reassuring interpretation of selected data by the very officials who have dodged the issue for 15 years claiming it is the condition, not the drugs. What the FDA did not show you is evidence to support that SSRI safety for any age group or any indication. They are all at risk. They failed to provide you a complete SSRI data analysis. They failed to provide you peer-reviewed critical analyses by independent scientists who have been proven right. FDA was wrong then; it is wrong now. Don’t collaborate in this. [But they eventually did]

Breggin commented that the FDA controlled and monitored the original pediatric studies because the drug companies did not do so on their own and failed to find a risk of antidepressant-induced suicidality in any age group. “Why would the FDA assume these same self-serving drug companies, left on their own again, would spontaneously begin for the first time to conduct honest studies on the capacity of their products to cause adult suicidality?”

In a linked document of two memos written by an Eli Lilly employee in 1990, Dr. Breggin noted where the individual questioned the wisdom of recommendations from the Lilly Drug Epidemiology Unit to “change the identification of events as they are reported by the physicians.” The person went on to say: “I do not think I could explain to the RSA, to a judge, to a reporter or even to my family why we would do this especially to the sensitive issue of suicide and suicide ideation. At least not with the explanations that have been given to our staff so far.” Those suggestions included listing an overdose in a suicide attempt as an overdose, even though (here he seems to be quoting from a policy or procedural statement) “when tracking suicides, we always look at all overdose and suicide attempts.” Eli Lilly brought the first SSRI, Prozac, to market in 1986.

Next time you hear someone say that the FDA studies only showed increased suicidality in children and young adults as opposed to adults, remember that the adult studies, unlike the pediatric studies, were not controlled, monitored or validated by the FDA. This is one more example of the extremes the FDA will go to in order to protect drug companies and their often lethal products.

The problems with antidepressants, most of which are SSRIs—selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors—were at least partially known as Prozac and its cousins were being developed and brought to market in the early 1990s. As the above discussion indicated, there seems to have been a disregard of the potential for multiple negative side effects from their use, up to and including the various forms of suicidality. The sleight-of-hand done by the drug companies, and apparently the FDA, means that many individuals are in the dark about the adverse side effects stemming from their SSRI medications.