The Medication Merry-Go-Round with Depression

There seems to be a paradigm shift brewing for how we explain depression. “Beyond the serotonin deficit hypothesis,” an article that appeared in Molecular Psychiatry, noted how the serotonin deficit hypothesis of depression has persisted among clinicians and the general public alike “despite insufficient supporting evidence.” The next month the journal Psychopathology published a study, “A Descriptive Diagnosis or a Causal Explanation?” that concluded leading professional medical and psychiatric organizations commonly confound a descriptive diagnostic label for depression with a causal explanation. Then there was a third study that explored whether the DSM adequately identified DSM disorders when someone was decreasing, switching, or discontinuing SSRIs/SNRIs following their long-term use.

The End of the Serotonin Theory of Depression

In 2022 an article in Molecular Psychiatry, “The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence,” concluded the serotonin theory has not produced convincing evidence of a biochemical basis for depression. The researchers suggested it was time to acknowledge that the serotonin theory of depression was not empirically substantiated. The flurry of criticism the article generated didn’t seem to stifle its message. “Beyond the serotonin deficit hypothesis” said in order to combat the eroding public trust in science and medicine (and also combat the rising mental health crisis), “researchers and clinicians must to be able to communicate to patients and the [general] public an updated framework of major depressive disorder (MDD).” These authors suggested that framework should be:

(1) accessible to a general audience, (2) [it should] accurately integrate current evidence about the efficacy of conventional serotonergic antidepressants with broader and deeper understandings of pathophysiology and treatment, and (3) [be] capable of accommodating new evidence.

They discussed how MDD could be understood as inflexibility in cognitive and emotional brain circuits that involved a persistent negative bias. Secondly, they reviewed how effective treatments for MDD enhanced mechanisms of neuroplasticity in ways that facilitated adaptive and emotional processing. Lastly, they considered how researchers, clinicians and other professional could present this framework when discussing MDD with patients or the general public. They also suggested language and metaphors they thought could be useful for effective communication about MDD. For a further discussion of “The serotonin theory of depression,” see: “Paradigm Shift Needed with Depression.”

Is MDD a Description or a Causal Explanation?

In “A Descriptive Diagnosis or a Causal Explanation?” two Finnish researchers observed: “Psychiatric diagnoses are descriptive in nature, but the lay public commonly misconceives them as causal explanations.” Kajanoja and Valtonen said it was not known to what extent this form of diagnostic circular reasoning—diagnoses being discussed as if they describe the causes of symptoms—was mistakenly reinforced by the health authorities themselves. They investigated the prevalence of misleading causal descriptions of depression in the information on the websites of authoritative mental health organizations. Most websites used language “that inaccurately described depression as a causal explanation to depressive symptoms.”

Most psychiatric diagnoses are descriptive: They describe states of mental distress and dysfunction but do not in themselves contain causal explanations. Nonetheless, diagnoses in psychiatry are commonly talked about as if they are concrete entities that explain the symptoms they describe. In this study, we examined whether health organizations themselves contribute to this logical fallacy. We searched for popular websites managed by leading mental health organizations, and evaluated whether they discussed the diagnosis of depression accurately as a description, or inaccurately as a cause for depressive symptoms. We found that the majority of websites presented depression as a cause, instead of a description of symptoms. We discuss the potential harmful consequences of inaccurately presenting descriptive psychiatric diagnoses as causes.

In “Depression Diagnoses Debunked,” SciTechDaily said Kajanoja and Valtonen selected the websites of English-language organizations that seemed to be the most influential ones providing information on depression. These organizations included the World Health Organisation (WHO), the American Psychiatric Association (APA), National Health Service (NHS) in the UK, Harvard and Johns Hopkins Universities, among others. They found most of the organizations portrayed depression as a disorder that caused symptoms and/or explained what caused the symptoms. None of the organizations presented the diagnosis of MDD as a pure description of symptoms. They said:

Presenting depression as a uniform disorder that causes depressive symptoms is circular reasoning that blurs our understanding of the nature of mental health problems and makes it harder for people to understand their distress. . . People seem to have a tendency to think that a diagnosis is an explanation even when it is not. It is important for professionals not to reinforce this misconception with their communication, and instead help people to understand their condition.

Misdiagnosing Antidepressant Withdrawal

A third study by Cosci, Chouinard and Chouinard published in Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics explored whether the DSM alone was adequate to identify psychiatric disorders when an individual was switching, decreasing or discontinuing a SSRI/SNRI. The researchers found that withdrawal/discontinuation symptoms were mis-formulated (misdiagnosed) as DSM-5 psychiatric disorders like a current panic disorder or recurrent major depressive disorder. They noted how existing diagnostic methods with the DSM do not take withdrawal/discontinuation phenomenon into account. The researchers used a new nosographic system, the Diagnostic Clinical Interview for Drug Withdrawal 1-New Symptoms of Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors or Serotonin-Norephinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (DID-W1), and found that: “In 58 cases (77.3%), the DSM-5 diagnosis of current mental disorder was not confirmed when the DID-W1 diagnosis of current withdrawal syndrome was established.”

Reviewing the Cosci, Chouinard and Chouinard article for Mad in America, “Antidepressant Withdrawal Commonly Misdiagnosed as ‘Mental Illness’,” Peter Simons said the researchers thought the fact that the DSM does not include criteria for withdrawal symptoms was a barrier to the accurate diagnosis and treatment of depression. “While the DSM asks clinicians to differentiate ‘mental disorders’ from drug-induced symptoms, it does not include drug withdrawal symptoms—from either recreational or prescribed drugs.” Therefore, Cosci, Chouinard and Chouinard suggested the DID-W1 be used to detect withdrawal induced by SSRI/SNRI discontinuation, decrease or switching all psychiatric medications. Limitations of the study included the small sample size, and that study participants were volunteers who were already seeking help for withdrawal reactions.

It seems that when switching, decreasing or discontinuing antidepressants (or antipsychotics) leads to circular reasoning—withdrawal symptoms that can be misdiagnosed as an emerging anxiety disorder, some other psychiatric disorder, or seen as the re-emergence of major depression. Without a tool like the DID-W1, what can a person do to better understand their problems and get off the medication merry-go-round for depression?

The Model of Drug Action May Be the Answer

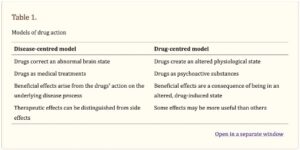

Joanna Moncrieff, one of the researchers who wrote “The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence”, has promoted what she calls “the drug-centered model of drug action.” She has written about it multiple times and her discussion can be found in The Myth of the Chemical Cure, on her blog in “Models of Drug Action,” and in “Research on a ‘drug-centred’ approach to psychiatric drug treatment” published in the peer-reviewed journal, Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences. In “Models of Drug Action,” she said she formulated two different models of drug action, the disease-centered model, and the drug-centered model. Also see “A Drug is a Drug is a Drug.”

The disease-centered model suggests that psychiatric drugs can reverse, or partially reverse, “the disease or abnormality that gives rise to the symptoms of a particular psychiatric disorder.” This model is borrowed from general medicine and describes drugs through the prism of disease or the collective pattern of symptoms the drugs are thought to treat. The important effects of the drugs—like with serotonin reuptake inhibitors— “are the ones they exert on the disease process.” All other effects are considered to be ‘side effects.’ And the therapeutic effects are believed to only be evident in people with the ‘disease.’

The drug-centered model suggests that psychiatric drugs induce an abnormal or altered state, but do not correct it. Psychiatric drugs like antidepressants are psychoactive substances like alcohol or heroin, and they modify the way the brain functions, producing changes in thinking, feeling and behavior. They exert their effects on the individual regardless of whether or not they have a mental condition (a drug is a drug). The drug-centered model suggests that some drugs may be useful therapeutically in some situations, but not by normalizing brain function. “They do it by creating an abnormal or altered brain state that suppresses or replaces the manifestations of mental and behavioural problems.” See also “Never Enough and No Free Lunch” and “Never Enough and Adaptation.”

See the following table for a comparison of the two models, taken from “Research on a ‘drug-centered’ approach to psychiatric drug treatment.”

When modern psychiatric drugs were introduced in the 1950s, they were understood according to a drug-centred model. Antipsychotics, for example, which were then known as ‘major tranquilisers,’ were regarded as a special sort of sedative. They were thought to have properties that made them uniquely useful in situations like an acute psychotic episode, because they could slow up thought and dampen emotion without simply inducing sleep, but they were not regarded as a disease-targeting treatment. By the 1970s, however, this view was eclipsed and the disease-centred model of drug action became dominant. Accordingly psychiatric drugs were regarded as specific treatments that worked by targeting an underlying disease or abnormality. The change is demonstrated most clearly in the way drugs have come to be named and classified. Prior to the 1950s drugs were classified according to the nature of the psychoactive effects they produce. Existing drugs were crudely classified as having either sedative or stimulant effects on the nervous system. After the 1950s, however, drugs came to be named and classified according to the disease or disorder they are thought to treat; antidepressants, antipsychotics and anxiolytics, for example.

The ascendance of the disease-centred model of drug action did not occur because of overwhelming evidence of the superiority and truth of the disease-centred model. There was not then, and is not now, convincing evidence that any class of psychiatric drugs has a disease centred or disease-specific action. There was not even any real debate about alternative theories of drug action. The disease centred model just took over and the drug-centred view simply faded away. People forgot there had ever been another way of understanding how psychiatric drugs might work.

In summary, we should set aside the serotonin theory of depression because it has not produced convincing evidence of a biochemical basis for depression. Psychiatric diagnosis appears to be circular reasoning that describes states of mental distress, but does not provide a causal explanation of that distress. The withdrawal symptoms when tapering, discontinuing or changing antidepressant medications leads to a misdiagnosis of recurrent major depression or another psychiatric disorder. We need to return to a drug-centered model of drug action to get off of the medication merry-go-round.

It seems we are beginning to pay attention to a question asked by psychiatrist Peter Breggin 25 years ago in Your Drug May Be Your Problem: “Do we know what we are doing to our brains and minds when we take psychiatric drugs?” Doctor Breggin said: “We simply do not understand the overall impact of drugs on the brain.”

Consider this extraordinary reality. The human brain has more individual cells (neurons) than there are stars in the sky. Billions! And each neuron may have 10,000 or more connections (synapses) to other brain cells, creating a network with trillions of interconnections. In fact, the brain is considered to be the most complex organ in the entire universe. With its billions of neurons and trillions of synapses, it is more complex than the entire physical universe of planets, stars, and galaxies . . .

Those trillions of interconnections between brain cells … are mediated by hundreds of chemical messengers (neurotransmitters), as well as hormones, proteins, tiny ions, such as sodium and potassium, and other substances. We have limited knowledge about how a few of these chemical messengers work but little or no idea as to how they combine to produce brain function.