What Does God Look Like?

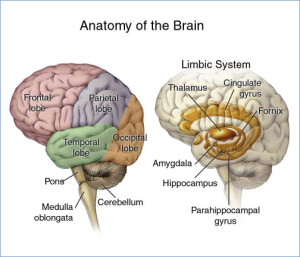

A neuroimaging study published in the journal Nature demonstrated that when a well-recognized face was shown to an individual, a single neuron in the person’s brain would fire. The researchers were able to show that a single unit in the left posterior hippocampus would fire “to all pictures of the actress Jennifer Aniston.” But the neuron did not respond to pictures of Jennifer Aniston together with Brad Pitt. In a previous study, the researchers found that individual neurons would fire selectively to various images—like animals or buildings. So it is possible that some people could have a single neuron that would fire when they see a familiar picture of Jesus—or Buddha. “That neuron could represent the cornerstone of their religious training and belief.” This adds a whole new way of looking at God as you understand Him.

The study mentioned above was “Invariant Visual Representation by Single Neurons in the Human Brain.” Here are links to the abstract and the full article. The above speculation of the possibility of a “God neuron” in your brain was by Andrew Newberg in his book, How God Changes Your Brain. Newberg wondered if it was possible that people could have a neuron or specific set of neurons that fired when they were asked to envision God. “As brain-scan technology becomes more refined, I suspect we will see that each human being has a unique neural fingerprint that represents his or her image of God.”

Newberg described how we are born with a neurological mechanism to identify objects. The first objects an infant learned to identify were family members and caretakers. We see this when a stranger looks at an infant and gets a frowned response. The child’s brain labels each new object it learns to recognize; the first of many steps that turn an image into a concept or a word. The simplest kind of word for a child to learn is a concrete noun, “because it refers to something the child can see, touch, or taste.” The neurological capacity of young children to comprehend abstract objects won’t fully develop until adolescence, so they can only readily understand the simplest concepts.

A young child’s brain has no choice but to visualize God as a face that is located somewhere in the seeable physical world, and that is what we find when we analyze the pictures drawn by children younger than ten.

Brain-scan studies show that nouns are linked to visual-object-processing regions of the brain. Each time a novel idea is introduced, there is increased activity in specific areas of the right hemisphere of the brain—“the same areas that construct our visual representations of reality.” So when a child is introduced to a spiritual concept, their brain will automatically give it a sense of realness and personal meaning. The brains of children who continue in religious education will modify their “spiritual map” as they are introduced to new ways of conceptualizing God. “So its not surprising to see children’s pictures becoming more complex as they mature.”

A German professor of religious education, Helmut Hanisch, did a study where he compared drawings of God from West German children, who attended Christian-oriented schools, to those of children who attended school in East Germany, where an official antireligious doctrine had been in place.

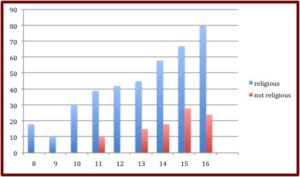

In the religious group, children between the ages of seven and nine represented God as a face or a person around 90% of the time. By the time they reached the age of sixteen, only 20% drew pictures of faces or people. Instead, they preferred symbolic representations of God. But this did not happen with the East German, nonreligious students. By sixteen, “80% of the nonreligious children still used people to symbolize God.” The following chart illustrates the findings of Hanisch, as they were shown in Greenberg’s book. The vertical axis reflects the percentage of images that were abstract. The horizontal axis reflects the age of the children.

There were also differences in their comments about God. The older religious children described a loving sense of God, while the nonreligious children saw God as powerless and weak. They often referred to war, misery, suffering and poverty. One 12-year old girl said: “I don’t understand why God is allowing all this. Therefore I don’t believe in God.”

Young people do not have the cognitive skills to articulate abstract concepts of God, but they can use their visual imagination to comprehend spiritual realms. Even in the adult brain, ideas appear to be associated with internal visual processes, and mathematicians often think in pictures when they describe the invisible forces of the universe. Even when we imagine the distant past or future events, we activate the visual-spatial circuits of the brain. In fact, if you cannot see, hear, touch, taste, or smell something, the brain’s first impulse is to assume that it doesn’t exist. Thus, for anyone, the brain’s first response is to assign an image to the concept of God.

Newberg said without this capacity for visual imagination, we would be barely able to think. Even when we sleep and dream, this capacity for visual imagination remains active. But children do not have the neural capacity to easily separate fantasy from fact, so they form beliefs that blur the boundaries of reality. Think here of the child who insists there are monsters under their bed. Children readily believe their nightmares are real, “while adults have advanced neural processes to help them analyze perceptual discrepancies.”

If you tell a child that God can see you, or listen to your prayers, then the child’s imagination will associate those qualities with the eyes and ears of a face. If you tell the same child that God gets angry, the brain will generate images of frowns, gritted teeth, or perhaps fists banging against a wall—visual constructions that represent how a child perceives anger in other human beings. If you tell your child that God performs miracles, then the internal imagery takes on superhuman traits. For example, one boy drew God with a cape and a large S on his chest.

Newberg said that based upon his research, he thought the more a person examined their spiritual beliefs, the more their experience of God would change. And if you could not or would not change your image of God, you might have problems tolerating people who held to different images of God. He said if you clung to your childhood image of God, you limited your perception of truth. He thought this was a drawback for any religion that insisted upon a literal, biblical image of God. “If you limit your vision, you might feel threatened by those who are driven to explore new [or different] spiritual values and truths.”

For both the secular individual and the biblical Christian, there is validity in what Newberg says. The reality of radical Islamists and Westerners who reflexively oppose all Islamists as a result, clearly illustrates Newberg’s observation. The growing criticism of conservative Christian beliefs with regard to changing social and political mores is another example. Even within Christianity we find infighting and disputes over how to interpret the first 11 chapters of Genesis, the authority and inerrancy of the Bible, the form of church government, what happens during the sacrament of communion, and so on.

However for the biblical Christian, there is a potential confusion, and perhaps a danger of slipping into postmodern or theological relativism, in what Newberg said as well. In order to avoid this, clearly make a distinction between God and how you image (view) God. What remains the same yesterday, today and tomorrow is God, and not how you imagine Him to be. Greenberg used the sense of the “image of God” because he was describing how children and adults visualize complex abstractions like God.

But when applied theologically to human beings, the term “image of God” has the sense that they were created (not visualized) in the image of God. Here “image” is used metaphysically and not visually. All humans are images of God in a metaphysical sense. So regardless of the differences in how they understand or view God (how they imagine Him), all people should be given the same toleration and respect as human beings created in the image of God.

Secondly, be aware that as a Bible-believing Christian, authority and power lies with God and His revealed Word, not your understanding (your image) of Him. Regularly Christians impute onto their views (images) of God the authority and power properly owed only to Him and his Word. And if there is any questioning of that personal image, they react as if the person questioned God, and not just their understanding of Him. I’d suggest such a Christian has implicitly violated the second commandment (found in Exodus 20), which forbids making an image of God. We see this more explicitly stated in the Westminster Larger Catechism, where it says the second commandment forbids the making of any kind of image of God, “either inwardly in our mind, or outwardly in any kind of image of likeness.”

So what does God look like to you? If you want, you can replicate an experiment Newberg has done with different groups of religious and nonreligious people—get a pencil or pen and a piece of paper and draw a picture of God. He suggested that you be spontaneous and draw whatever comes to your mind. Don’t worry about the quality of your art, but complete the drawing in two minutes. When you finish, write a brief description of its meaning below the picture.

Nearly everyone pauses for a long time—even longer than when we asked, “What does God feel like?”—which tells us there is increased activity occurring in many parts of the brain, especially in the visual, motor, association, cognitive, and emotional centers. Indeed, the question appears to be so neurologically challenging and psychological provocative that some people simply refuse to draw anything. Children, however, have no difficulty with the request, and delight in drawing their impressions of God.