Telling the Truth About Marijuana and Psychosis

In January of 2019 Alex Berenson’s book, Tell You Children: The Truth About Marijuana, Mental Illness and Violence, was published. He hoped it would at least make his readers skeptical of the pro-marijuana arguments that advocates have peddled for the last twenty-five years. He said, “I hope it will open your eyes to the mental illness and violence that marijuana causes in your community.” In his career as a reporter, he made some enemies and gave an example of when private detectives, who were hired by an angry executive, chased him down the Long Island Expressway. “Yet nothing in my career prepared me for the reaction to this book.”

The article in Wikipedia on Tell Your Children, seemed to capture the rancor Berenson stirred up. He was said to have made “harsh” claims that cannabis use causes psychosis and violence, claims that were denounced by members of the scientific and medical communities. Two scientists who wrote an opinion piece for The Guardian said his assertions were “misinformed and reckless.” A group of 75 scholars and medical professionals signed an open letter that disagreed with Berenson, accusing him of cherry-picking data, attributing cause to mere associations and selection bias. “His work is a polemic based on a deeply inaccurate misreading of science.”

In an Afterword Berenson wrote in October of 2019 for the e-book edition, he said it was crucial to understand that these critics did not claim his book presented false or incorrect data, or was in any other way was “factually inaccurate.” “They can’t, because it doesn’t and isn’t.” He added that “misinterpret” and “cherry-pick” were word critics used when they could not find actual factual errors. He found the anger against what he wrote almost bizarre. “One can be aware that cannabis can cause mental illness and still favor legalization. But the cannabis industry, academics, and journalist-advocates would rather try to shout down anyone who raises it.”

Despite the attacks, both pro- and anti-legalization forces have said the book has affected the public debate. Berenson said, “And the evidence about the serious health harms has only mounted since January [of 2019].” Let’s look at some of this new evidence about the serious health harms from marijuana. There were two studies published in JAMA Psychiatry that appeared to support Berenson’s understanding of the science. Follow the links and see if he has been misreading the science.

A study done in 2018 and published in March of 2019 in JAMA Psychiatry found that prenatal cannabis exposure may be associated with a small increase in the proneness for psychosis during middle childhood. Another study published in May of 2019 in the journal JAMA Psychiatry suggested that risks for cannabis use problems and anxiety disorders were higher among those using high-potency cannabis. There was a small increase in the likelihood of psychotic experiences, but this risk decreased with an adjustment for the frequency of cannabis use.

Dr. Marta Di Forti is one of the leading researchers in the world for cannabis and psychosis. In a previous meta-analysis Di Forti and other researchers showed there was a positive association between the extent of cannabis use and the risk of psychosis. They observed “a consistent increase in the risk of psychosis-related outcomes with higher levels of cannabis exposure” in all the studies included in the meta-analysis. “Although this meta-analysis shows a strong and consistent association between cannabis use and psychosis, a causal link cannot be unequivocally established.”

Di Forti and others also noted that epidemiological evidence demonstrates that cannabis use is associated with an increased risk of psychosis in “Traditional marijuana, high-potency cannabis and synthetic cannabinoids: Increasing risk of psychosis.” The researchers said concern that cannabis might induce psychosis is not new. In 1896 the Scottish psychiatrist T. Clouston visited the Cairo asylum and noted that 40 out of 253 people in the hospital had insanity attributed to the use of hashish. By the 1960s, this view was commonly ridiculed as ‘reefer madness.’ The implication was that those who believed marijuana could induce psychosis were mad, rather than those who consumed it. This seems to be the thrust of the approach from those scholars and medical professionals that signed the open letter disagreeing with Berenson.

However, there have been several longitudinal studies showing cannabis as a risk factor for psychosis. “Nine out of twelve found that cannabis use was associated with a significantly increased risk of psychotic symptoms or psychotic illness.” In a 2015 study for Lancet Psychiatry, Di Forti and others found that high-potency cannabis users in south London had three times the risk of having a psychotic disorder than those who never used cannabis.

The following link is to a talk Dr. Di Forti gave in December of 2019 before the American College of Pharmacology, where she presented data from her research in South London, at a clinic where she works. First, she asked, does the frequency and type of cannabis matter?

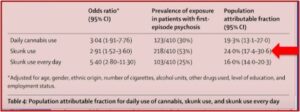

The charts below from her presentation showed that individuals who used hash did not have rates that were statistically different than the controls. However, she had already said that hash was found to have a combination of THC and CBD, where the “skunk” or high-potency cannabis had very little CBD. Notice in the first graph that the probability of an individual experiencing a psychotic disorder increased as the frequency and strength of cannabis increased to daily use of high-potency skunk. The second chart shows both the use of high-potency cannabis and daily use of high-potency cannabis increased the chance of having a first-episode psychosis by 53% and 25% respectively.

Di Forti then asked, why should potency matter? Why should the amount of THC in cannabis matter? The results of a 2016 study she contributed to, “The Effects of continuation, frequency, and type of cannabis use on relapse,” found that once someone had a psychotic episode, if they continued to use cannabis, especially high-potency skunk, they “are much more likely to have a bad clinical outcome.” There was an increased risk of relapse, there were more relapses, there were fewer months until a relapse occurred, AND more intense psychiatric care was needed after the onset of psychosis.

Adverse effects associated with continued use of cannabis after the onset of a first episode of psychosis depend on the specific patterns of use. Possible interventions could focus on persuading cannabis-using patients with psychosis to reduce use or shift to less potent forms of cannabis.

In May of 2019, Di Forti and others published this research in The Lancet. The strongest independent predictors of whether an individual would have a psychotic disorder or not were daily use of cannabis and the use of high-potency cannabis. Starting cannabis use by the age of 15 modestly increased the odds for a psychotic disorder, but not independent of the frequency of use or of the potency of the cannabis used. “The odds of psychotic disorder among daily cannabis users were 3.2 times higher than for never users, whereas the odds among users of high-potency cannabis were 1.6 times higher than for never users.” Compared with individuals who never used, individuals who used high-potency cannabis daily had four-times higher odds of psychosis. Their findings were consistent with previous evidence suggesting that using high-potency cannabis has more harmful effects on mental health than does the use of weaker forms.

Our findings confirm previous evidence of the harmful effect on mental health of daily use of cannabis, especially of high-potency types. Importantly, they indicate for the first time how cannabis use affects the incidence of psychotic disorder. Therefore, it is of public health importance to acknowledge alongside the potential medicinal properties of some cannabis constituents the potential adverse effects that are associated with daily cannabis use, especially of high-potency varieties.

Serendipitously, it seems Marta Di Forti reviewed Tell Your Children by Alex Berenson for Amazon on January 18, 2019. She titled her review “Outstanding and engaging narrative.” She said:

This book is a rare and compelling combination of journalistic rigor, elegant writing and engaging style. A unique appraisal of the sociological and scientific facts feeding the never-ending debate on the good and bad of the most popular recreational drug in the world. A “must” read for everyone that can read or listen.

In his Afterword, Berenson cited a review study of twenty-six meta-analyses and literature reviews on cannabis and psychosis, “Cannabis use and psychosis: a review of reviews” published on September 28, 2019 in the European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. He said its findings were no surprise. There was consistent support for cannabis use being a contributing cause of psychosis.

The scientific literature indicates that psychotic illness arises more frequently in cannabis users compared to non-users, cannabis use is associated with a dose-dependent risk of developing psychotic illness, and cannabis users have an earlier onset of psychotic illness compared to non-users. Cannabis use was also associated with increased relapse rates, more hospitalizations and pronounced positive symptoms in psychotic patients.

Although not research, in August of 2019 the U.S. Surgeon General published an advisory on Marijuana Use and the Developing Brain. He noted how the marijuana available today is much stronger than it was in the past. The THC concentration in marijuana plants has increased three-fold between 1995 and 2014, 4% to 12% respectively. Marijuana available in some state dispensaries has an average THC concentration between 17.7% and 23.2%. Concentrated products, known as dabs or wax, may contain between 23.2% and 75.9%.

The risks of physical dependence, addiction, and other negative consequences increase with exposure to high concentrations of THC and the younger the age of initiation. Higher doses of THC are more likely to produce anxiety, agitation, paranoia, and psychosis.

The ad hominem arguments against Alex Berenson and Tell Your Children just do not hold up. Attempting to misdirect the debate over the significance of what Berenson elegantly documents and say he should contend with the failures of marijuana prohibition, illustrates how his critics argue past him. The open letter noted above is an example of this: “Weighed against the harms of prohibition, including the criminalization of millions of people, overwhelmingly black and brown, and the devastating collateral consequences of criminal justice system involvement, legalization is the less harmful approach.” The Guardian noted that Berenson was open to that position, although he disagreed with it.

“You can believe that cannabis is a real risk for psychosis and violence and still believe it should be legal,” he said. “That’s a totally reasonable position to take. Just tell the truth.”

For more on marijuana and psychosis, see: “Cannabis and Psychosis: More Reality than Satire.”