Increasing Your Awareness of Alcohol Misuse

Here’s a random statistic for you, according to Capital One. Did you know that Americans spent $3.9 billion on alcohol (mostly beer) for the Fourth of July in 2022? So, what’s the problem with that? Well, the CDC published a study in March of 2024 that estimated an average of 138,000 people died annually from alcohol-related causes in 2016-2017, which increased to 178,000 in 2020 to 2021. The causes included motor vehicle accidents, alcohol poisoning, cancer and cirrhosis.

The PBS News Hour said the main factor for this increase was the COVID-19 pandemic. Alcohol became easier to purchase with the rise of home delivery services, according to Dr. Michael Siegel, of Tufts University. The stress, loss of life from the virus, and isolation from family and friends contributed to mental health struggles that led many people to self-medicate with alcohol. He thought this rise in alcohol-related deaths was “most likely to hold steady,” unless the U.S. takes actions like raising taxes on alcohol to bring down consumption, which has worked in other countries. According to NIAAA, the 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) said 29.5 million people over the age of 12 (10.5%) had an alcohol use disorder in the past year.

The CDC has something called ARDI, the Alcohol-Related Disease Impact Application, where you can see national and state estimates of alcohol-related health impacts, including alcohol-attributed deaths, years of potential life lost, and estimates of the proportion of death from various causes attributed to alcohol. For example, in Pennsylvania there were a total of 6,624 deaths due to excessive alcohol use. Among the chronic causes of death, 787 were due to alcoholic liver disease (520 from cirrhosis), 699 due to hypertension in a total of 1,472 deaths caused by heart disease and stroke. Among acute causes of death there were 382 from motor vehicle traffic crashes, 371 from suicide, and 291 from homicide.

The CDC study of deaths from excessive alcohol use from 2016-2021 is here. The study found that the annual number of deaths from excessive alcohol use increased nationally by more than 29% from 2016-2017 to 2020-2021. There were 12,719 deaths from alcoholic liver disease, and 37,317 from heart disease and stroke. Acute causes of death included 15,055 from motor vehicle crashes, and 9,801 from suicides.

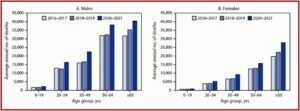

There were increases in the alcohol-related deaths for all age groups. The article suggested that over one in eight total deaths of adults aged 20-64 were from excessive alcohol use. Death rates were highest in men and adults aged 50 to 64, but are increasing more rapidly among women and younger adults. See the following graphs taken from the CDC study.

The nearly 23% increase in the deaths from excessive alcohol use that occurred from 2018–2019 to 2020–2021 was approximately four times as high as the previous 5% increase that occurred from 2016–2017 to 2018–2019. Increases in the availability of alcohol in many states might have contributed to this disproportionate increase. During the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020–2021, policies were widely implemented to expand alcohol carryout and delivery to homes, and places that sold alcohol for off-premise consumption (e.g., liquor stores) were deemed as essential businesses in many states (and remained open during lockdowns). General delays in seeking medical attention, including avoidance of emergency departments for alcohol-related conditions; stress, loneliness, and social isolation; and mental health conditions might also have contributed to the increase in deaths from excessive alcohol use during the COVID-19 pandemic.

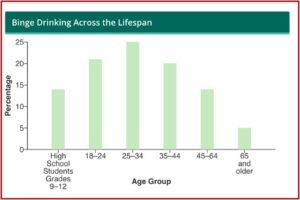

The prevalence of binge drinking among adults aged 35-50 was higher in 2022 than in any other year of the past decade, and could contribute to future increases in alcohol-related deaths. Binge drinking is a pattern of drinking that brings your blood alcohol content (BAC) to .08% or higher. This happens when a woman has four or more drinks or a man has five or more drinks within 2 hours. The CDC said most people who binge drink are not dependent on alcohol. Binge drinking is most common among younger adults aged 18-34 and more common among men than women. See the following graph.

A small percentage of adults who drink account for half of the 35 billion total drinks consumed by US adults yearly. Twenty-five percent of binge drinkers do so at least weekly, and 25% consume at least 8 drinks per occasion. Proven strategies to prevent excessive alcohol use and the related harms include: increase alcohol taxes; enforce laws prohibiting alcohol sales to minors; hold retailers accountable for harms the result from illegal serving or selling alcohol; avoid the privatization of alcohol sales; maintain limits on the days and hours when alcohol can be sold; and regulate the density of alcohol retailers. See “Excessive Alcohol Use” by the CDC.

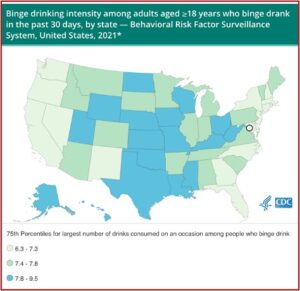

See the following CDC data table for the number of drinks consumed on an occasion when people binge drink (the black circle is for Washington DC):

Older Adults Are Drinking More Alcohol

The rise in drinking is particularly concerning for people 65 and older, with greater health impacts. Dr. George Koob, the director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, said this is a particular concern for women. He said Baby Boomers (born between 1946 and 1964) have always tended to drink more, as well as use other drugs, “so the percentage of older people who drink is going up.” The number of people who binge drink, develop alcohol use disorder, and die from alcohol is on the rise. This could place an increased burden on our healthcare system, according to Dr. Koob.

Bodily changes as you age make you more susceptible to some of the harms from drinking alcohol. Your tolerance for alcohol drops. People in their 70s aren’t going to react to alcohol in the same way they did in their 30s. There is a decrease in the enzyme that metabolizes alcohol, meaning the response to a drink will be stronger in older people as their metabolism gets slower. There is a reduction in the percentage of water in the bodies of older people, leading to a higher blood alcohol concentration.

There is also a larger impact on the driving performance, reaction time, memory and balance in older than younger drinkers. “Balance is particularly a problem considering that the leading cause of injuries among adults ages 65 and older — and studies suggest falls while intoxicated tend to be more severe.” Ninety percent of older adults are taking at least one medication regularly, and combining them with alcohol can be risky. Dr. Koob said a study found that older adults are more likely to experience depressed breathing than young adults from a combination of alcohol and opioids. And alcohol can weaken the body’s ability to fight off infections, like with COVID-19.

It can be harder to spot problem drinking in older adults who are retired, live alone or socialize less, as the signs are less overt. The current Dietary Guidelines for Alcohol given by the CDC are one drink or less daily for women and 2 drinks or less daily for men. Less is better, according to Dr. Koob:

We believe that people at any age could benefit from stepping back and taking a look at their current relationship with alcohol. We also think that cultivating alternatives to alcohol use for relaxation, socializing, and dealing with stress can result in less alcohol use and better health.

April is Alcohol Awareness Month and older adults are at a heightened rick of alcohol misuse due to a variety of environmental, medical and social factors. See the Alliance for Aging Research for an interview with Dr. Koob. Embedded in the article is a YouTube video of the interview.