Is Adult ADHD the Latest Fad Diagnosis? Part 2

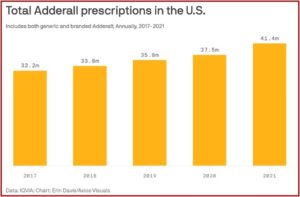

Dramatic increases in ADHD diagnoses and prescriptions for ADHD medication noted in Part 1 are not just happening in the U.S. BBC Scotland claimed, “The number of adults receiving an NHS prescription for ADHD had increased seven-fold over the last 10 years.” Data obtained from Public Health Scotland indicated 26,000 patients were prescribed ADHD medications in 2022/23. Almost half were adults. The number of adult prescriptions rose steadily from 1,603 in 2013/14, to 5,920 in 2019/20, and then doubled to 12,182 by 2022/23.

Although ADHD content on social media platforms like TikTok contributes to the current problem of over diagnosis, it didn’t create it. In Saving Normal, Allen Frances, who was the chair for the DSM-IV, said until the mid 1990s ADHD medications had been off patent for decades and could be purchased generically for pennies a pill. There was no advertising to patients or marketing to doctors. Then several newly patented—and expensive—medications ADHD medications came to market. And then drug companies were given the right to advertise to consumers.

The blaring propaganda message was the usual—ADHD is extremely common, often missed, and accounts for why Johnny is a behavioral problem and isn’t learning in school. “Ask your doctor.” Armies of eager sales reps filled the offices of pediatricians, family doctors, and psychiatrists peddling a pill that would magically prevent classroom disruptions and solve home meltdowns. Parents, teachers, and physicians were recruited in an all-out effort to identify and aggressively treat ADHD.

PsychCentral listed the top 25 psychiatric medications in 2020. The top three most expensive medications, making the most money for their manufacturers, were all ADHD medications: methylphenidate (Concerta, $3.28 billion), lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse, $3.01 billion), and amphetamine/dextroamphetamine (Adderall, $2.35 billion). Adderall had the fourth most prescriptions written with 26.24 million, Concerta was 10th with 18.55 million prescriptions, and Vyvanse was 20th with 8.64 million prescriptions.

Dr. Frances Levin of Columbia University, an internationally recognized expert in adult ADHD, said: “It’s difficult to get a clear picture of how many individuals in this country fit a clinical definition for ADHD, when there are no U.S. guidelines for diagnosis and evaluation of ADHD in adults.” Practice guidelines currently exist only for childhood ADHD. She thought both underdiagnosis and overdiagnosis of ADHD are happening. The American Society of ADHD and Related Disorders (APSARD) recently appointed a special committee to write guidelines for adult ADHD in the U.S. Dr. Levin co-chairs the committee. Her understanding of the rise in overdiagnosis is dramatically different than Dr. Frances.

She said in the early 1990s, there was a belief that ADHD diminished with age as well as concern in the scientific community about the validity of diagnosing ADHD in adults. “Then in the 1990s, the increase in diagnoses of childhood ADHD led to greater public awareness.” More adults recognized and reported symptoms in themselves and adult ADHD was added to the DSM-IV in 1994. Older psychiatrists, she said, weren’t schooled in evaluating and treating adults with ADHD; and now younger clinicians don’t get much training or experience with this population. The creation of uniform standards will address a critical need for healthcare providers and patients.

In Saving Normal, Dr. Frances there was no real reason to think that the prevalence of attentional and hyperactivity problems has actually increased. “We now diagnose as mental disorder attentional and behavioral problems that used to be seen as part of life and of normal individual variation.” He suggested six contributing factors to the increase of diagnosing childhood ADHD. There were: wording changes in DSM-IV; heavy drug company marketing to doctors and advertising to the public; extensive media coverage; pressure from parents and teachers to control unruly children; extra time on tests and extra school services if a child had an ADHD diagnosis. “And finally, the widespread misuse of prescription stimulants for general performance enhancement and recreation.”

Unchastened by the false “epidemic” of ADHD already running rampant among kids, DSM-5 has set the stage for creating a new epidemic of ADHD in adults. As usual, the experts worry so much about missed cases, they fail to consider the much greater risk of overdiagnosis. Attentional problems and restlessness are nonspecific and extremely common among normal adults and in those suffering from any of the other mental disorders. The easy path to adult ADHD suggested by DSM-5 will mislabel many normal people who are dissatisfied with their ability to concentrate and get their work done, especially when they feel bored and don’t like the work they’re doing. It will also misdiagnose those whose problem in concentrating is really caused by something else—e.g., substance abuse, bipolar disorder, depression, all the anxiety disorders, psychotic disorders, and many others. No one should ever get diagnosed or treated for adult ADHD until all of these are first ruled out as the primary cause—lest inappropriate stimulant treatment may worsen their already existing psychiatric problems.

He went on to say adult ADHD was already too easily diagnosed. Symptoms are mostly subjective and based on self-perceptions of poor concentration and task performance. “The DSM-5 lowering of requirements will capture many adults who want to be sharper but don’t have specific or serious enough problems to qualify for a mental disorder.” He said fake adult ADHD would be common in college students, in people with demanding jobs, and in those who struggle to stay awake, like long-haul truck drivers. Remember that Allen Frances was the chair for the DSM-IV.

An article by Allen Frances on Psychtherapy.net thought the numbers given for the prevalence of current adult ADHD were absurdly high. In the general population, the current rate for adult ADHD is reported to be 4.4% (5.4% for males and 3.2% for females). He thought the best guide was that by Keith Conners, considered to be the father of the ADHD diagnosis. Conners thought the rate of childhood ADHD was around 2-3% and about half that number in adults. Frances then gave the following as reasons for the overdiagnosis of adult ADHD.

Almost all mental disorders and almost all substance addictions can perfectly mimic ADHD since they can cause its two classic symptoms — hyperactivity and trouble focusing attention.

- Real or imagined attention problems are a very common complaint among perfectly normal people.

- Getting an ADHD diagnosis is a gateway to legal speed — desired for performance enhancement, all-nighters for school tests or work assignments, recreational purposes, or for sale into the extensive secondary ADHD pill market.

- Careless diagnosis and prescribing by MDs.

- An inevitable consequence of overdiagnosing ADHD in kids is overdiagnosing ADHD in adults.

- Promotion via drug companies and social networking.

Frances said the risks of overdiagnosing ADHD in adults were:

- Meds used for ADHD are usually quite harmful if the person’s symptoms are due to another psychiatric disorder that has been missed — especially bipolar disorder, depression, schizophrenia, eating disorders, or anxiety disorder.

- Overdiagnosis of ADHD results in over-medication with drugs that cause harmful side effects and can lead to or worsen addiction.

- There is now a huge secondary market for ADHD meds, especially on college campuses.

- There is also a nationwide shortage of ADHD meds for patients who really need them — because the meds are so often prescribed for those who don’t or diverted to the illegal market.

His bottom line was that most of what looks like adult ADHD is not adult ADHD. Most of it is normal behavior, sometimes caused by another psychiatric or medical problem or substance use. ADHD drugs are not safe unless carefully used for accurately diagnosed ADHD. Frances thought it was past the time to stop the adult ADHD fad before it gained more traction.

Easy access to legal “speed” has created a large illegal secondary market of diverted pills. ADHD drugs have become the campus recreational drug of choice at parties and the performance-enhancement drug of choice for all-nighters during finals week. Legal speed can cause many medical and psychiatric adverse effects, and emergency room visits for complications are skyrocketing. The Drug Enforcement Agency and the FDA are now trying to contain the epidemic — but their efforts are too little/too late. The adult ADHD fad will be stopped only if clinicians and patients fight against its seduction and insist on more careful diagnosis and cautious treatment.

Writing for Psychiatric Times, Mark Ruffalo and Nassir Ghaemi noted in “The Making of Adult ADHD” that twenty years ago, the consensus view in American academic psychiatry was that ADHD rarely persisted into adulthood. Now, adult ADHD is the “diagnosis du jour.” The rates of diagnosis and the prescriptions for the psychostimulant drugs that treat them are skyrocketing. They thought adult ADHD was a case of disease mongering, rather than psychopathologists and psychiatric nosologists missing the disorder for more than a century. Along with Allen Frances, they also associated the rise in diagnosis of adult ADHD to marketing by the pharmaceutical industry.

The rise in diagnosis of adult ADHD fully coincides with marketing by the pharmaceutical industry when Eli Lilly and Company got the first US Food and Drug Administration indication for this label with atomoxetine (Strattera) in 1996. Since that date, many academics have been promoting the concept of adult ADHD. The adult ADHD market has become a multibillion-dollar industry, with the rise of digital companies specializing in online diagnosis and treatment—some of which have come under legal scrutiny.

They noted retrospective studies, (that look backwards to determine if cases of childhood ADHD continue into adulthood), commonly find 50% to 60% of childhood ADHD persists into adulthood. “However, these data are disproven by prospective studies, which repeatedly show that about 80% of children with ADHD do not continue to have that diagnosable condition, followed prospectively either into young adulthood or even for 33 years into their fourth decade of life.” Ruffalo and Ghaemi don’t think that adult ADHD is a scientifically valid diagnosis. They don’t mean that the symptoms don’t exist. Adults do have problems with attention, concentration, focus, memory and other related abilities. However:

What we mean is that these symptoms have not been shown to be the result of a scientifically valid disease (adult ADHD) and are better explained by more classic and scientifically validated psychiatric conditions, namely diseases or abnormalities of mood, anxiety, and mood temperament.

They concluded the history of psychiatry shows the field has been vulnerable to a host of diagnostic fads. “Adult ADHD is the latest of such fads, and a careful review of the scientific literature reveals that the range of ADHD-like symptoms in adults is more accurately explained by other empirically validated psychiatric disorders.”