Risking Psychosis and Mania with ADHD

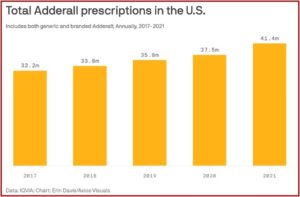

A recent study, “Risk of Incident Psychosis and Mania with Prescription Amphetamines,” found that individuals taking high doses of amphetamines (i.e., Adderall or Vyvanse) had a fivefold increased risk of developing psychosis or mania compared to those who weren’t taking stimulants. Study participants who experienced psychosis or mania were more likely to have a family history of bipolar disorder or psychosis, to take stimulants that had not been prescribed to them, or to use cannabis daily. The researchers suggested caution should be exercised when prescribing high doses of amphetamines, and clinicians should be carefully monitored and screened for symptoms of psychosis and mania.

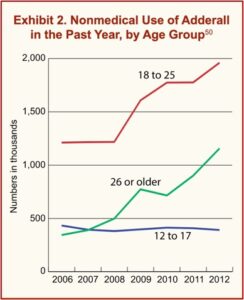

The lead author of the study said in The New York Times that when working as an inpatient psychiatrist, she noticed that teenagers and young adults were often being hospitalized for new psychosis or mania symptoms without a history of either. Many of these people with first-episode psychosis or mania were taking high doses of stimulants supposedly for ADHD. It was not clear why some people seemed to have a greater risk of manifesting psychosis or mania. A pediatric neurologist and ADHD expert said he had patients on 60-milligram Adderall tablets daily with no problems. He speculated the amphetamine triggered an underlying predisposition and thought more research was needed to understand the risk factors for developing psychosis or mania on stimulants.

The researchers defined a high dose as more than 40 milligrams of Adderall, 100 milligrams of Vyvanse or 30 milligrams of dextroamphetamine. The medium dosage (20 to 40 milligrams of Adderall, 50 to 100 milligrams of Vyvanse or 16 to 30 milligrams of dextroamphetamine) was associated with a 3.5 times higher risk of psychosis or mania.

Amphetamine Use and Psychiatric Disorders

Past studies have linked amphetamine use and psychiatric disorders. “Amphetamine-Related Psychiatric Disorders” noted that, “Psychosis following amphetamine use is characterized by persecutory delusions, visual hallucinations, and symptoms resembling acute psychosis most commonly observed in schizophrenia.” There was also a pattern of high dosage and daily use being associated with higher risks of substance-induced psychosis. “Amphetamines impair the cognitive thought process and subsequently precede acute psychosis. This suggests that continued impairment due to amphetamine use is a precursor to psychosis.”

Amphetamine-induced psychosis appears to have a more rapid recovery. It also seems to resolve with abstinence from stimulants. The NYT article described a 26-year-old female who fits this observation. She had her first psychotic episode while taking Vyvanse for ADHD. She had stopped taking it while pregnant and didn’t resume it until six months postpartum.

She’d often forget when she had taken her last pill and would take one when she remembered—probably leading to her taking more than her prescribed daily dose. She began felt euphoric and highly energetic. “I felt like my brain was exploding with connections.” She thought she was a “super detective,” uncovering people and organizations engaging in child sex trafficking. She also thought someone was drugging her and her baby.

She was hospitalized, taken off Vyvanse, and prescribed an antipsychotic medication. The delusions stopped, but then resurfaced a few weeks later. “Over the course of months, she began to feel like herself again.” The lead author of “Risk of Incident Psychosis and Mania with Prescription Amphetamines” said it can take time for the delusions to clear. “People have to take off a semester or even a year from college before they can go back. So it is very disruptive.”

The woman’s brother was diagnosed with schizophrenia, so at first, she wondered if she was developing a psychotic disorder. But almost a year later, the psychosis and mania have not returned. “She recently began taking a much lower dose of amphetamine: 10 milligrams of Adderall.”

However, the issue isn’t as straightforward as an association between an underlying predisposition for psychosis or mania and stimulant ADHD medication. Medical News Today reported the lead author of the “Risk of Incident Psychosis” study as saying there was limited evidence that prescription amphetamines were more effective in higher doses. “Physicians should consider other medications our study found to be less risky, especially if a patient is at high risk for psychosis or mania.” Another psychiatrist agreed, saying the study prompts an immediate reconsideration of the risk-benefit analysis of prescribing, especially for patients with a history of mental health issues. He suggested using extended-release formulations to minimize peak plasma levels, and emphasize nonpharmacologic interventions as first-line treatments whenever possible.

Additionally, with stimulant use there is a need for regular mental health evaluations and more frequent follow-ups, especially during the initiation and titration phases of amphetamine therapy. There needs to be particular care taken when considering use of amphetamines in patients with a history of psychosis, bipolar disorder, or other psychiatric vulnerabilities.

Another psychiatrist said researchers should explore whether there is a clear causal relationship between high-dose amphetamine prescriptions and the risk of psychosis and mania. The “Risk of Incident Psychosis” study did not find there was an increased risk of psychosis and mania among those who used methylphenidate drugs like Concerta or Ritalin. An article in Science Alert noted both Adderall and Ritalin raise dopamine levels. However, Adderall increases the release of dopamine, while Ritalin blocks the reabsorption of dopamine.

The Ethics of Challenge Studies for Psychosis

When you read the recent reports of the “Risk of Incident Psychosis” study, it may appear the correlation and possible causation of psychosis or mania from stimulant drugs was new information, but it’s not. And the further investigation of whether high dose amphetamine causes psychosis or mania raises some potential ethical questions.

I’ve talked to an individual working to abstain from misusing cocaine, a stimulant, who described paranoid delusions when using cocaine. When using cocaine, he’d think undercover police were hiding in the bushes across from his 2nd floor apartment, but he could never see them. So, he called in an anonymous tip for a crime happening in the next block of his street, assuming the unseen officers would have to go and investigate. He never saw anyone respond to his “tip.” When he was abstinent, he could describe and laugh about the delusion he had while under the influence of cocaine.

The association of psychosis and mania from using stimulants has also been investigated in psychiatric research for over fifty years. In 1998, Robert Whitaker and Dolores Kong wrote an article for the Boston Globe, “Testing takes human toll.” The authors described how more than 2,000 individuals had been part of a disturbing series of experiments by psychiatric researchers into the biology of psychosis with so-called challenge studies.

In their published accounts, doctors have told of injecting mentally ill patients with drugs designed to exacerbate their delusions and hallucinations. In prestigious journals, they have described studies in which they withheld effective antipsychotic medication from desperate patients who stumbled into hospital emergency rooms. In precise, clinical terms, they have reported how they deliberately stopped giving medication to stabilized schizophrenic patients to see how quickly they became sick again.

These studies were designed to gain knowledge that might lead to improved treatments for schizophrenia and related illnesses. But the experiments offered no possibility of therapeutic benefit to the subjects and exposed them to some measure of psychic pain and risk of long-term harm.

Moreover, this controversial line of experimentation has been marked by repeated instances in which researchers failed to fully disclose the risks to the mentally ill patients and obscured their true purposes.

Dr. Jeffery Lieberman, a former president of the American Psychiatric Association, was one of the researchers who conducted methylphenidate challenge tests. Remember where methylphenidate was not found to precipitate psychosis or mania in the “Risk of Incident Psychosis” study? Yet it was Lieberman’s preferred stimulant in older challenge studies to do exactly that. Dr. Lieberman acknowledged the induced symptoms could be “scary and very unpleasant.” He admitted that some patients got worse, but thought “the symptoms never exceeded the range of severity that occurred in the course of their illness previously.” See “Psychiatry, Diagnose Thyself! Part 2,” for more information on the Boston Globe article and Jeffery Lieberman.

The future research of whether high dose amphetamine use precipitates psychosis or mania essentially means those experiments will likely be some kind of challenge studies. In “Challenge Experiments,” chapter 26 of The Oxford Textbook of Clinical Research Ethics, Franklin Miller and Donald Rosenstein said challenge experiments were among the most controversial forms of clinical research. “They involve experimental interventions aimed at perturbing the biological or psychological functioning of human beings for the purpose of developing scientific knowledge about diseases and their treatment.” No precise definition of challenge experiments has been developed and there is no possible medical benefit for the enrolled participants.

What makes challenge studies morally problematic is their potential to exploit research participants for the good of society. As in the case of all clinical research, this form of experimentation stands in need of ethical justification in accordance with standard ethical requirements. To be ethical, challenge experiments must have scientific or social value; employ valid methods of investigation; select participants fairly; minimize risks and justify them by the potential knowledge to be gained from the research; be reviewed and approved by a research ethics committee; enroll participants who have given informed consent or with ethically appropriate surrogate authorization; and they must be conducted in a way that adequately protects the rights and well-being of research participants.

If there is limited evidence that prescribed amphetamines are more effective in higher doses, and other less risky medications are available to patients who are at high risk for psychosis or mania, why do an experiment to confirm what we already know? What is the risk-benefit of prescribing high doses of stimulant medications to patients with a history of mental health issues? Shouldn’t nonpharmacologic interventions be used as first-line ADHD treatments whenever possible?