Just before the publication of the DSM-5 in 2013, the then director of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), Thomas Insel, said the institution would no longer use the DSM to guide its research. In a blog post, which is no longer available, he said: “While DSM has been described as a ‘Bible’ for the field … it is, at best, a dictionary, creating a set of labels and defining each.” The strength of the DSM had been to standardize these labels, but “[t]he weakness is its lack of validity,” and “[p]atients with mental disorders deserve better.”

While Insel’s blog was reported as a “bombshell,” NIMH’s decision to move away from DSM criteria had been in the works for several years. As early as 2010, the agency began to steer researchers away from the traditional DSM categories. Psychologists like Frank Farley thought the measures of agreement between experts for several disorders in the DSM-5 were terrible. “What it suggests is that we need to go back to the drawing board.”

But psychiatrists thought both Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) and DSM were necessary. On a practical level, researchers and physicians need DSM to help characterize and treat patients. And drug development for psychiatric disorders had supposedly become stagnant because of “our lack of understanding of the biological roots of psychiatric disease.” RDoC is a framework for research, not a diagnostic manual; but it hasn’t been tested yet. In the meantime, the DSM is useful in psychiatry. For the sake of patients, “it’s important to communicate that we do have good treatments for mental disorders.”

The Illusion of Diagnosis

When the DSM–III was published in 1980, its developers made the claim that there was “far greater reliability than had been previously obtained with the DSM–II.” The manual itself claimed that: “reliability for most classes in both phases is quite good and, in general, “is higher than that previously achieved using DSM–I and DSM–II.” The developers of the DSM–III declared that the reliability problem they had set out to solve was greatly improved. Ironically, there was never a comparison of the DSM–III’s reliability with earlier DSM versions, a natural follow up to the 1974 Spitzer and Fleiss study (See Part 1) that helped launched the revision process. Further reliability studies after the DSM–III were generally seen as useless, but reliability comparisons of the DSM–III and DSM–III–R were done by others.

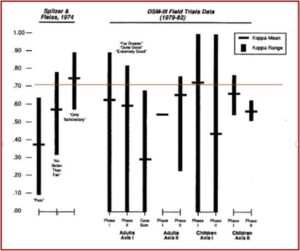

In The Selling of the DSM, Stuart Kirk and Herb Kutchins used the kappa statistic and the standards articulated by Spitzer and Fleiss in their classic 1974 article to compare the earlier reliability study to the data available for the DSM–III and DSM–III–R. The following chart, originally in “The Myth of the Reliability of DSM” and currently in The Selling of the DSM, illustrates that comparison. Notice that the rhetoric of the DSM–III’s reliability being “far greater reliability than had been previously obtained with the DSM–II” is seen as patently false in this comparison. If anything, the kappa statistics for the DSM–III Field Trials data were slightly lower.

An examination of the data comparison in the above chart leads to the following conclusions: 1) The kappa values were unstable, sometimes ranging from 0 to 1—the entire spectrum from chance to perfect agreement; 2) In three of four comparisons, there was a pattern of lower average kappa scores in the second phase of the trials, where higher reliability scores were expected; 3) with written case studies—a method that supposedly would insure more control of the evaluations, and expect greater reliability scores—lower reliability scores were found. There were also methodological and statistical problems with the data for the DSM–III Field Trials.

A further reliability study of the DSM III–R was done by some of the major participants in the development of the DSM-III. While they utilized several techniques that had been developed to improve diagnostic reliability, their study still had disappointing results. The kappa values were not that different from the pre–DSM-III studies, and in some cases appeared to be worse. The kappa values for the patient sample were within Spitzer’s fair category (.61 mean score, with ranges from .40 to .86). The kappa values for the non–patient sample were only poor (.37 mean score, with ranges from .19 to .59). There were 37 kappas reported for the various diagnostic categories in the patient sample. Only one was above .90; 21 were in the only satisfactory range; 27 were in the no better than fair range; and 21 were in the poor range. Despite the claims of greater scientific progress in DSM diagnosis, its reliability appears to have improved very little in the three decades after the release of the DSM-III.

The DSM-5

Allen Frances, the chair of the DSM-IV, has become a vocal critic of modern psychiatry and diagnosis with the DSM-5. He warned in the Psychiatric Times that the DSM-5 would dramatically increase the rates of mental disorder by “cheapening the currency of psychiatric diagnosis;” and by arbitrarily “reducing thresholds for existing disorders and introducing new disorders with high prevalence.” He thought this would create millions of newly mislabeled “patients,” resulting in unnecessary and potentially harmful treatment and stigma.

It would accomplish this by introducing five new, very common “‘disorders that together will mislabel many millions of people now considered normal.” Also, the DSM-5 lowered the threshold for many existing disorders, “turning normal grief into depression and dramatically increasing rates for attention-deficit disorder and generalized anxiety disorder.” It was “simply irresponsible not to be concerned about or measure the major impact this will have on the over-use of medication, on stigma, and on the misallocation of scarce resources.” According to Frances, this would create millions of newly mislabeled ‘patients.’

In a 2012 article published in The American Journal of Psychiatry entitled “DSM 5: How Reliable is Reliable Enough?” the authors suggested that the quality of psychiatric diagnoses should be consistent with what is known about the reliability of diagnoses in other areas of medicine. Note the difference in assessment from what we’ve discussed above.

Most medical reliability studies, including past DSM reliability studies, have been based on interrater reliability: two independent clinicians viewing, for example, the same X-ray or interview. While one occasionally sees interrater kappa values between 0.6 and 0.8, the more common range is between 0.4 and 0.6.

From these results, to see a κI [kappa] for a DSM-5 diagnosis above 0.8 would be almost miraculous; to see κI between 0.6 and 0.8 would be cause for celebration. A realistic goal is κI between 0.4 and 0.6, while κI between 0.2 and 0.4 would be acceptable. We expect that the reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient) of DSM-5 dimensional measures will be larger, and we will aim for between 0.6 and 0.8 and accept between 0.4 and 0.6. The validity criteria in each case mirror those for reliability.

See the following chart that compares what Spitzer and Fleiss said about kappa statistics in their 1974 study to the kappa statistics for a DSM-5 diagnosis just described.

| Spitzer and Fleiss Study | DSM 5 Reliability | ||

| Kappa statistics | Kappa statistics | ||

| Uniformly High | .9 | Almost Miraculous | Above .8 |

| Satisfactory | .6 to .9 (.7 mean) | Cause to Celebrate | .6 to .8 |

| Fair | .3 to .7 (.5 mean) | Realistic | .4 to .6 |

| Poor | .1 to .6 (.4 mean) | Acceptable | .2 to .4 |

Allen Frances said DSM-5 was not-so-subtly warning us that the reliability results from its field trial came in so low that we should accept a level of diagnostic agreement far below the universally accepted minimum standards. He said while the people working on the DSM-5 meant well and genuinely believe their suggestions will help patients, “The problem is that they are researchers who have worked in ivory tower settings with little experience in how the diagnostic manual is often misunderstood and misused in actual practice.” He further lamented in “The International Reaction to DSM-5”:

The credibility of DSM-5 has been irrevocably compromised by the recklessness of its decisions; the weak scientific support; and the poor reliabilities in the failed DSM-5 Field Trials. I doubt DSM-5 will remain the international standard for research journals; it will almost certainly not gain any clinical following outside the US; and it will also probably lose its role as the lingua franca of American psychiatry.

What can be done now to restore credibility? If APA were really serious about DSM-5 being a living document and subject to correction, it would immediately commission a neutral Cochrane-type review of its changes to evaluate whether they stand up to real evidence-based scrutiny. I am convinced that none would (with the possible exception of autism).

Of course, it would have been far better had DSM-5 heeded much earlier the many calls for an independent review of its scientific justification. Psychiatry would have been saved much embarrassment had DSM-5 been either self-correcting or amenable to outside correction.

But, it is much better to do this far too late than not at all. Better to admit to mistakes and regain credibility, than to soldier on and be ignored.

We must protect against the real danger that all of psychiatry will be tainted by the folly of DSM-5. This would be unfair to clinicians and dangerous for patients. Psychiatry is an essential and successful profession when it sticks to what it does well. DSM-5 was an aberration-not a true reflection of the field.

In 2022 the DSM-5 Text Revision (DSM-5-TR) was published. The main goal was to update the descriptive text, but there were also some significant changes, including the addition of some diagnostic entities and modifications in diagnostic criteria and specifier definitions. The three added diagnostic entities were Prolonged Grief Disorder, Unspecified Mood Disorder, and Stimulant-Induced Mild Neurocognitive Disorder. There were changes in diagnostic criteria or specifier definitions implemented for more than 70 disorders. “While most of these changes are relatively minor, a number are more significant, and address identified problems that could lead to misdiagnosis.” I believe the APA decided to ignore Allen Frances’ advice and just soldier on.

See Part 1 of this article for a discussion of what led to the revisions in DSM diagnosis discussed here.