“Patty” was 28 years-old and weighed 409 pounds when she enrolled in a radical year-long weight loss program supervised by Vincent Felitti in 1985. Patients did not eat any food; they would drink five glasses of water a day plus a nutritional supplement called Optifast. After 51 weeks on the diet, Patty’s weight was down to 132 pounds. She remained at that weight for three weeks, but then gained 39 pounds over the next three weeks. In “Adverse Childhood Experiences,” Felitti said he was puzzled, “and so was Patty.”

Then Patty admitted she was a sleep walker who binged on food as she wandered about at night. When she woke up in the morning, she would find open cans and boxes of food. “She would also cook at night.” When Felitti asked her what she thought was happening with her, she said the men at work were saying she looked attractive. Still confused, Felitti asked what those comments might have to do with her eating at night. “She told me that she began overeating at 11, about a half a year after her grandfather began sexually abusing her.”

Soon after Patti confided in him, Felitti and his colleagues at Kaiser Permanente in San Diego began to ask other obese patients about whether they also had a history of sexual abuse. “We were shocked. Of the first 286 patients we asked, 55% reported a history of abuse.”

In 1990, Felitti traveled to Atlanta for a national conference on obesity where he shared his findings on Patty and others who were struggling with the long-term effects of sexual abuse. David Williamson, a researcher at the CDC, thought Felitti’s work had enormous importance for the country, and said he would need to conduct a large epidemiological study in the general population. This led to a twenty-year collaboration with Williamson on the ACE study.

From 1992 to 1994, Felitti regularly interviewed patients to see what other early traumas they might have experienced besides sexual abuse. That’s when he came up with a list of the ten most common adverse child events, which in addition to sexual abuse include such experiences as physical abuse, parental alcoholism, and parental mental illness. He turned this list into a questionnaire, which he could use to conduct a formal study.

The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study began in 1995 and was first published in The American Journal of Preventive Medicine in 1998: “Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Manty of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults.” Seven categories of adverse childhood experiences were compared to measures of adult risk behavior, health status and disease. Felitti et al found that more than half of respondents reported at least one, and 25% reported 2 or more categories of adverse experiences. There was a graded relationship between the number of adverse childhood experiences and “each of the adult health risk behaviors and diseases that were studied.”

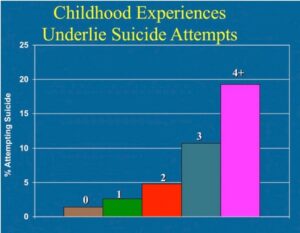

Persons who had experienced four or more categories of childhood exposure, compared to those who had experienced none, had 4- to 12-fold increased health risks for alcoholism, drug abuse, depression, and suicide attempt; a 2- to 4-fold increase in smoking, poor self-rated health, ≥50 sexual intercourse partners, and sexually transmitted disease; and a 1.4- to 1.6-fold increase in physical inactivity and severe obesity. The number of categories of adverse childhood exposures showed a graded relationship to the presence of adult diseases including ischemic heart disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, skeletal fractures, and liver disease. The seven categories of adverse childhood experiences were strongly interrelated and persons with multiple categories of childhood exposure were likely to have multiple health risk factors later in life.

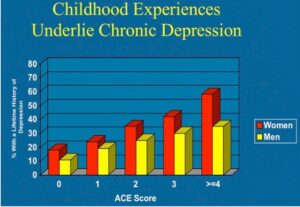

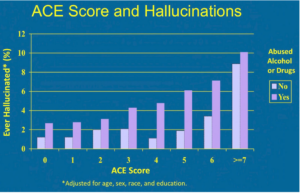

Among their findings the researchers reported that adults with four or more ACEs were four times more likely to have a depressive episode and twelve times more likely to have attempted suicide in the past year than participants with no ACEs. Other psychiatric issues in adulthood similarly rose with the frequency of adverse child experiences for chronic depression, suicide attempts and hallucinations. See the following graphs taken from “Adverse Childhood Experiences.”

Over the past two decades, over 100 papers in leading medical journals have followed Felitti’s original paper. In 2017, Huges et al published a metanalysis of the harmful effects of ACEs on health, “The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health ” in The Lancet Public Health. There were moderate associations of increased risk among individuals with at least four ACEs for smoking, heavy alcohol use, cancer, heart disease, poor self-rated health, and respiratory disease; strong associations with sexual risk taking, mental health issues and problematic alcohol use. The strongest associations were for problematic drug use and interpersonal and self-directed violence.

Despite accumulating knowledge about the lifelong effects of ACEs, their prevention and the development of resilience and support for those affected have been slow to move up political agendas. International attention is increasingly focusing on prevention of violence against children, often emphasizing protection of girls. Although girls are especially vulnerable to certain ACEs (eg, sexual abuse), both sexes are routinely victims of multiple ACEs and both feel their long-term effects. In fact, the high prevalence of ACEs combined with their effect on life-course health suggests a substantial but largely hidden contribution to Global Burden of Disease estimates, which include childhood sexual abuse, yet not many other ACEs. Thus, smoking and alcohol use are leading risk factors for burden of disease, and in this study, individuals who had had at least four ACEs were more than twice as likely to be current smokers or heavy drinkers and almost six times as likely to drink problematically than were those who had had no ACEs. Consistent with such elevated risks, NCDs [non-communicable diseases] including respiratory disease, diabetes, cancers, and heart disease (the leading cause of death globally), were also substantially more likely in those with at least four ACEs than in those with none.

The ACE study led by Felitti closed in 2015; Ferlitti and his original collaborators have all retired. But he still speaks around the world, advocating for people to use the data from the ACE study. He lamented that there remains a lot of resistance. He thinks there is a pressing need for increased investments in policies that strive to prevent child abuse and improve parenting skills. This should be combined with efforts “to identify and treat individuals at high risk for developing numerous debilitating health problems, physical and psychological, related to adverse childhood experiences.” Although most health professionals are familiar with the ACE study, few doctors screen for ACEs.

The CDC has continued the struggle to inform the public about ACEs. Sixty-one percent of all adults reported they have experienced at least one type of ACE. Nearly 1 in 6 reported they had experienced four or more types of ACEs. Under “Fast Facts,” the CDC noted how environmental factors like growing up in a household with substance use problems, mental health problems or instability from parental separation of household members being in jail or prison undermined a child’s sense of safety, stability and bonding. ACEs were linked to chronic health problems, mental illness, and substance use problems as adults.

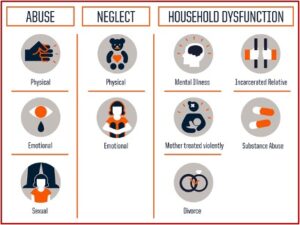

In “Risk and Protective Factors,” it was acknowledged there are many risk and protective factors beyond the original ten. ACEs are categorized into three groups: abuse, neglect and household challenges. Then each category is further divided into ten subcategories. Some additional adverse childhood traumas include homelessness, losing a caregiver, watching a sibling be abused, bullying, teen dating violence, community violence, and others. See the following graphic for the most commonly mentioned adverse experiences of the original ACE Study.

What happened to Patty? Her story ended tragically, as if she had been holding a dead man’s hand of aces and eights. She eventually regained all of her weight and then disappeared from Felitti’s clinic for twelve years. When she returned, she got bariatric surgery and lost 94 pounds, but then she struggled with chronic depression. She said it felt as if her will was crumbling. “Patty eventually had five stays in psych hospitals, during which she underwent three courses of ECT. In the end, nothing seemed to help her, and she died a few years ago.” Let’s see if we can change the outcome for future Pattys.