Neuroscience News described a study that highlighted how peer pressure and misperceptions about college drinking norms can lead students to drink more heavily than they intend. “Many students believe their peers consume more alcohol than they actually do, which can increase risky behavior and negative outcomes.” Published in Substance Use & Misuse, “Perceived Norms and Alcohol-Related Consequences Among College Students” found that alcohol-related Protective Behavioral Strategies (PBS) aimed at avoiding excessive drinking could significantly reduce alcohol use and related problems among college students who see heavy drinking as normative.

The 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) found almost half of full-time college students reported drinking alcohol (46.3%) in the past month, with 27.9% saying they engaged in binge drinking in the past month. Binge drinking is consuming five or more drinks containing alcohol for males and four or more drinks for females on the same occasion within a couple of hours. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) warned that repeated episodes of binge drinking in the teen years can alter adolescent brain development and cause persistent deficits in social, attention, memory, and other cognitive functions.

The study published in Substance Use & Misuse explored how social influences, especially peer pressure, impacted alcohol use and misuse among young adults. A confidential online survey on alcohol use was given anonymously to 524 students at a large public university. “College students are particularly at risk of misperceiving their peers’ alcohol consumption partly due to a variety of campus social events where alcohol is served such as parties, tailgating, and pre-gaming, which can influence their personal drinking outcomes by feeling pressured to keep up.”

The lead author of the study observed how students may think that if other students are drinking five or six drinks a day, they should also drink that amount. “But it has been established that this is mostly inaccurate. That misperception can lead to heavy episodic drinking and negative consequences.” To address those misperceptions, the researchers examined whether PBS techniques could reduce the influence of these misperceived norm.

The protective strategies (PBS) included drinking slowly and avoiding drinking games reduced alcohol-related harm. They helped students stay in control of their consumption, even in the midst of a heavy drinking culture. The regular use of PBS lowered the risk for injury, academic problems, and alcohol misuse. “What the evidence shows, and what our study confirmed, is that once students begin to use these strategies, they reduce the risk of experiencing negative consequences like drunk driving.” Over time, the consistent use of these strategies could lower the overall rates of alcohol-related harm like falls, unsafe sexual behavior, and car crashes.

Researchers estimated that binge drinking accounted for $191.1 billion (76.7%) of the $249 billion economic cost of excessive drinking in the U.S. Be aware that binge drinking occurs with individuals who don’t meet the criteria for an alcohol use disorder, AUD. Occasional binge drinking doesn’t necessarily mean you have an AUD. But binge drinking on a regular basis may be a sign of a developing AUD. So, how can you tell if your binge drinking is becoming an AUD? First, we need to understand how alcohol effects the brain of anyone who drinks alcohol, problematically or not.

Reward Pathway of the Brain

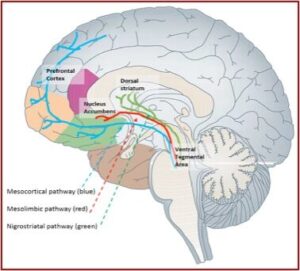

One of the brain circuits activated by alcohol or drugs is the mesolimbic (midbrain) reward system, commonly referred to as the pleasure pathway. This system generates signals in a part of the brain called the ventral tegmental area (VTA) that results in the release of the chemical dopamine (DA) in another part of the brain, the nucleus accumbens (NAc). See the figure below, used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International.

This release of DA into the NAc results in feelings of pleasure and euphoria from alcohol and other drugs. Other areas of the brain (like the basal ganglia) create a lasting record or memory that associates these good feelings with the circumstances and environment in which they occur. The drug or alcohol experience can result in an intense memory of the experience, and lead the individual to seek future times of euphoria with that substance. These memories, called conditioned associations, often lead to the craving for drugs or alcohol when the person re-encounters those people, places, or things, and can trigger the individual to seek out more euphoric experiences.

Notice the blue, mesocortical pathway in the figure and its presence in the prefrontal cortex area of the brain. The prefrontal cortex plays a critical role in various cognitive and behavioral functions such as judgement, impulse inhibition, moral reasoning and decision-making, managing emotions, and suppressing inappropriate responses (self-control), among other functions. Alcohol and other psychoactive drugs will stimulate the mesolimbic system and then effect the prefrontal cortex, influencing its cognitive and behavioral functions. The greater the amount of alcohol or drug consumed, the greater is its effects on these cognitive and behavioral functions, potentially leading to a substance use disorder, to addiction.

Neurobiological Framework for Addiction

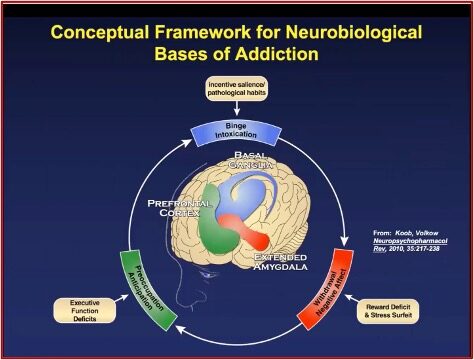

George Koob and Nora Volkow published an article in Neuropsychopharmacology, “Neurocircuitry of addiction,” that described the brain’s involvement in alcohol use disorder, and addictions in general. There is also a short video on YouTube (7 minutes) where Koob described this model. It has three stages: Binge Intoxication, Withdrawal Negative Affects, and Preoccupation Anticipation (see the graphic below). At the first stage, Binge Intoxication, you become intoxicated with alcohol. This stage involves behaviors derived from the pleasurable effects of alcohol. When you are drinking, the stimuli you associate with drinking, take on rewarding properties. Those stimuli or triggers can then actually motivate you to seek to drink.

The second stage, Withdrawal, Negative Affects, suggests that once you have engaged in overdoing alcohol, there’s a negative aftereffect. This includes hangovers for the person who simply drinks too much. But when the person has progressed to the level of a moderate to severe alcohol use disorder, the Withdrawal effects become increasingly negative. “So, it’s basically a state of physical signs of withdrawal, but also emotional signs of withdrawal. Basically, you feel terrible; there’s dysphoria. It can also be life-threatening.” The domains of dysfunction here have to do with diminishing your reward systems, and increasing of the stress systems in your brain.

The third stage is the Preoccupation Anticipation, or craving stage. This usually happens when you stop drinking, perhaps when you’ve entered into a prolonged period of abstinence from drinking. There are also negative effects on your stress systems and deficits in your executive function system. You can have trouble making decisions properly, or be impulsive. It can be difficult to delay reinforcement or resist the desire or craving for the next drink.

From a neurobiological perspective, these stages overlap. But they are also separated into different circuits. So, what’s illustrated here is the Binge Intoxication stage that involves the basal ganglia, a very basic part of our brain that we use for motivated behavior in seeking out things in the environment that are necessary for a living. The Withdrawal Negative Affect stage illustrated in red here is the extended amygdala, which incorporates part of our brain that’s involved in fear and stress; and avoiding dangerous things and dangerous situations. And that’s activated during the Withdrawal Negative Affect stage. And the Prefrontal Cortex is the green bit here, is actually the front end of our brain; the part of our brain where we make decisions. . . There are deficits, there are problems—there [is a] loss of function in the prefrontal cortex. And since this is the overall controller of the basal ganglia, pleasure system and the extended amygdala fear and stress system, you can understand how these all three interact.

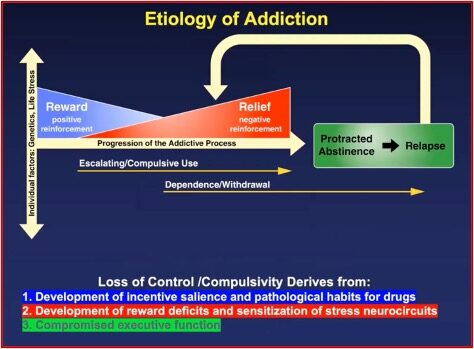

This results to the etiology of addiction, illustrated in the following graphic and summary of where loss of control and compulsivity in active drinking and drug use is derived.

Addiction is conceived as a progression in severity. Alcohol use disorder has mild, moderate and severe stages. When you reach the moderate and severe stage, you move from the Reward part (1) in the blue with positive reinforcements to drink more, to the Relief or negative reinforcement part (2), as addiction progresses. It’s described as negative reinforcement because you now take the drug to fix the problem that the drug caused (i.e., being miserable). You begin to take the drug to be less miserable, but the drug makes you even more miserable. There is escalating, compulsive use; a growing dependence on the substance and an increased experience of withdrawal and craving when not using.

In the Protracted Abstinence (3) of the Relapse stage, when you’ve stopped drinking, there are changes in the executive functioning of your prefrontal cortex. You experience compromised executive functioning, as described above. “We need time for those to heal; to come back to normal.” These changes are described by other clinicians as post-acute withdrawal symptoms.

Notice that in the Koob-Volkow model of addiction individual factors, genetics and life stress precede the addictive process, which has progressively decreasing positive reinforcement and progressively increasing negative reinforcement. Escalating, compulsive alcohol or drug use increases (as does loss of control) with continued use, and precedes the emergence of a physical dependence/withdrawal, which hardens the loss of control/ compulsivity. Loss of control begins as the inability to predict how substance use will influence a person’s thinking, feeling or behavior; and ends as a loss of control over using—the person ingesting the substance.

This last observation on loss of control is my own, and not part of what Koob said about the Koob-Volkow model of addiction. However, I believe it is consistent with the Cycle of Addiction on the NIAAA website, and the Koob-Volkow model which it uses. When binge drinking results in progressive negative reinforcement and an inability to establish and maintain either social patterns of drinking or abstinence from alcohol, binge drinking becomes an AUD, an alcohol use disorder.

For further discussion of loss of control and substance use disorders, see “Misdiagnosing Substance Use,” “Never Enough and No Free Lunch,” “Never Enough and Adaptation,” or “Dimming the Experience of Pleasure and Addiction.”