Neuroscience News recently reported on an observational study that found adults prescribed gabapentin six or more times for chronic lower back pain faced a significantly higher risk of dementia (29%) and mild cognitive impairment (85%) within 10 years. These risks were particularly evident in adults aged 35-64, with the rates of cognitive decline doubling or tripling over those who did not use the drug. Under the brand name of Neurontin, gabapentin was originally approved by the FDA in 1994 as a secondary treatment for epilepsy, in other words to be used when patients failed to responds to other anti-seizure drugs. It is currently recommended to treat only focal seizures and neuropathic pain, but has broad off label use to treat issues such as lower back pain, nerve injury and other pain conditions, as well as insomnia, anxiety, restless legs syndrome, bipolar disorder and alcohol use disorder. Presciently in 1999, it was referred to as the “snake oil” of the 20th century by a pharmaceutical company executive.

In a short YouTube video, Neuroscience News described how gabapentin became the go-to drug for chronic pain, especially lower back pain, because it’s perceived as safer and less addictive than opioids. “What’s even more surprising is how more vulnerable younger adults appear to be to developing dementia and cognitive impairment.” As this was an observational study, it cannot prove gabapentin caused these problems. “Gabapentin may still play a valuable role in pain management, but this evidence reminds us to weigh the benefits against the potential risks.”

The original research study described by Neuroscience News, “Risk of dementia following gabapentin prescription in chronic low back pain patients,” was published in Regional Anesthesia & Pain Medicine. The researchers said the risks of impairment from gabapentin increased further with repeated prescriptions. Patients prescribed gabapentin 12 or more times had a higher incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment than those prescribed gabapentin 3-11 times. There was a clear dose-response trend. The more prescriptions, the greater risk to the person. The researchers concluded that, “Physicians should monitor cognitive outcomes in patients prescribed gabapentin.”

How Gabapentin Became “Snake Oil”

So how did a medication originally approved as a secondary anti-seizure medication become a treatment for such a wide variety of conditions, enough to be referred to as snake oil? CBS News reported a Pfizer executive said in an email, “Gabapentin is the ‘snake oil’ of the twentieth century. It has been reported to be successful in just about everything that they have studied.” Estimates were that up to 94% of all Neurontin/gabapentin sales were for off-label use.

In The Truth About Drug Companies, Marcia Angell said even though the FDA approved Neurontin as a secondary treatment for epileptic seizures in 1994, its patent was due to expire in 1998. According to Angell, the pharmaceutical company Park-Davis began to target doctors to prescribe it for unapproved, off-label uses, “mainly common but vague conditions like pain and anxiety.” Although doctors are legally permitted to prescribe an FDA approved drug for any use whatsoever, it is illegal for a drug company to market a drug for off-label uses. So, Parke-Davis developed what they thought was a workaround strategy.

The company hired medical education and communication companies to prepare research articles and then paid legitimate academic researchers to put their names on the articles as authors. This so-called research fell below the standard required by the FDA to approve a drug to treat a particular condition. Angell said the studies were small and poorly designed. “Some of the articles contained no new data at all, just favorable comments about Neurontin.” Once the articles were published in academic journals, “medical liaisons” would visit doctor’s offices to answer questions about the “research” and urge them to prescribe gabapentin to treat the off-label condition.

Parke-Davis then sponsored educational meetings and conferences. The “authors” of the papers would describe the positive results of the drug’s off-label uses. Not only were the speakers paid, “but often the doctors in the audience were paid” to be consultants. This was to get around the anti-kickback laws. “Consultant meetings were sometimes little more than vacations for potential high prescribers of Neurontin.”

The result was Neurontin became a blockbuster drug, with over 2 billion in sales for 2003. “About 80 percent of prescriptions that year were for unapproved uses—conditions like bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress, disorder, insomnia, restless legs syndrome, hot flashes, migraines, and tension headaches.” In fact, Neurontin became an all-purpose restorative for chronic discomfort. This marketing strategy led to the executive’s comment that gabapentin was “the ‘snake oil’ of the twentieth century.”

After being extended, the patent for Neurontin expired and a generic version of Neurontin (gabapentin) went on sale in August of 2004. The website Drugs.com reported that Neurontin sales in 2004 were approximately $2 billion dollars. In 2005, gabapentin sales dropped to $259.4 million. It dropped from the 10th bestselling drug in 2004 to the 123rd bestselling drug in 2005. Pfizer, as a result of acquiring Parke-Davis, would eventually admit to improper off-label marketing of gabapentin and pay $945 million in three separate cases (criminal and civil) for off-label unapproved uses of gabapentin, according to Fierce Pharma.

For a more complete discussion of these events, see “Twentieth Century Snake Oil,” “The Evolution of Neurontin Abuse” and “Foolishness with Gabapentin.”

Abuse and Over Prescribing of Gabapentin

Nevertheless, gabapentin was able to overcome its illegal marketing problems and resume its place as one of the ten-most prescribed medications in the United States as gabapentinoids (gabapentin and pregabalin/Lyrica) were said to be safer alternatives to opioids for a variety of pain conditions.

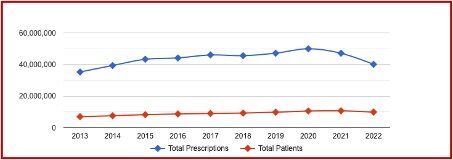

The following chart from ClinCalc indicated that in 2013 gabapentin was prescribed an estimated 35,264,270 times to 6,966,594 patients and ranked as the 14th most prescribed medication. By 2022 gabapentin had increased to the 10th most prescribed medication, with an estimated 9,889,546 patients and 40,141,486 estimated prescriptions. Its ranking has been relatively stable as the 10th most prescribed medication since 2019.

While the use of gabapentin rebounded, there were growing concerns that gabapentinoids were becoming overprescribed and being abused. A research letter to JAMA Internal Medicine, “Gabapentinoid Use in the United States 2002 Through 2015” reported the use of gabapentinoids had more than tripled between 2002 and 2015. The use of the medications was concentrated among individuals “who were older with numerous comorbidities and/or had numerous opioid prescriptions and/or had a benzodiazepine prescription.” The author said caution was advised in using gabapentinoids with long-term opioid users “given the lack of proven long-term efficacy and the known and unknown risks of gabapentinoid use.”

Pain News Network noted how this author’s research added to the growing body of evidence that pregabalin and gabapentin are overprescribed and being abused. Sales had steadily increased, in part because CDC prescribing guidelines recommend the two drugs as alternatives to opioids. Gabapentinoids were also being used recreationally by individuals who have found the medications enhance the effects of heroin and other opioids.

In “Gabapentin and Pregabalin for Pain—Is Increased Prescribing a Cause for Concern?” The New England Journal of Medicine noted that clinicians who were desperate for alternatives to opioids may have lowered their threshold for prescribing gabapentinoids to patients with various types of noncancer pain:

But even if the increasing use of gabapentinoids reflects — at least in part — a desire among clinicians to prescribe possibly safer alternatives to opioids, we believe there are several reasons to be concerned about this trend. First, reasonably robust evidence supports the efficacy of some medications for off-label uses, but that isn’t the case for gabapentinoids. We found that most recently published clinical studies of gabapentinoids for pain examined single-dose or short-course gabapentinoids for mitigating postoperative pain, an indication that isn’t relevant to general outpatient practice. Relatively few clinical trials have assessed the use of gabapentinoids in the common pain syndromes for which they are prescribed off-label — and many of those trials were uncontrolled or inadequately controlled and of short duration. Among the few well-conducted, properly controlled, double-blind studies, results have been mixed at best. In a recent rigorously conducted placebo-controlled trial, pregabalin was ineffective for patients with painful sciatica.

Second, gabapentinoids can have nontrivial side effects. Sedation and dizziness are relatively common, and some patients experience cognitive difficulties while taking these drugs. For example, in the sciatica trial, 40% of patients taking pregabalin reported dizziness, as compared with 13% of those taking a placebo. Although these adverse effects aren’t always severe and are reversible when the drugs are discontinued, gabapentinoids are often prescribed together with other drugs that have central nervous system side effects. Such polypharmacy might affect neurologic function in subtle but clinically important ways.

Third, evidence suggests that some patients misuse, abuse, or divert gabapentin and pregabalin. Some users describe euphoric effects, and patients can experience withdrawal when high doses are stopped abruptly. The likelihood of gabapentinoid abuse is reportedly heightened among current or past users of opioids and benzodiazepines. Whether misuse and abuse of gabapentinoids will become an important public health issue remains to be seen.

Although gabapentinoids may be useful as an alternative for opioids, clinicians should not assume they are an effective approach for most pain syndromes “or a routinely appropriate substitute for opioids.” They have a potential for abuse and pregabalin is a Schedule 5 controlled substance. Gabapentinoids are typically combined with other substance like benzodiazepines, alcohol, opioids, buprenorphine (Subutex) or methadone to get high. Additional research is needed to clearly define their role in pain management and assess their abuse potential.