Mad in America reviewed an interesting study of multiple analysts who examined the same data. These researchers gave twenty-nine teams made up of 61 analysts the same data set to address the same research question: are soccer referees more likely to give red cards to players with darker skin than those with lighter skin? Presuming that quantitative psychological science delivers objective facts, we would think these analysts would come to the same results. “Unfortunately, it appears that this is not the case.”

How can this be? In Common Grace, Cornelius Van Til said there was no such thing as a “brute,” uninterpreted fact. The idea of brute, uninterpreted fact is the presupposition of any fact of science. “A ‘fact’ does not become a fact, according to the modern scientist’s assumptions, till it has been made a fact by the ultimate definitory power of the mind of man.” According to Van Til, the modern scientist pretends to be merely a describer of facts, but in reality, is a maker of facts. Nevertheless, this tendency towards the subjective can be minimized in modern science.

The above noted research study, “Many Analysts, One Data Set” was published in the journal Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science. It found that 20 teams (69%) found a statistically significant positive effect while 9 teams (31%) did not find a significant relationship. In other words, 20 teams thought referees were more likely to give red cards to darker-skinned players, while 9 teams thought referees did not appear to discriminate according to skin tone. “Even amongst the researchers that found a positive result, the effect ranged from very slight to very large.” The reason for the varied findings seemed to be the result of the choice of statistical analysis and the covariates the researchers examined.

The statistical methods chosen by the research teams varied widely, including linear regression, multilevel regression, and Bayesian statistics. The covariates (other factors that might influence the results) chosen by the research teams also varied widely, with 21 different combinations being chosen. Three teams, for example, used no covariates, while three other teams only controlled for the effects of player position as a covariate.

The researchers suggest that the different decisions made during this process, including what other factors to control for, what type of analysis to run, and how to deal with randomness and outliers in the dataset, all lead to divergent conclusions.

None of the analyses were merely wrong or poorly conducted. “The differences in result could not be explained by the researcher’s pre-existing biases about the answer, or by the experience level of the researchers, after tests were run to rule out these possible explanations.” Typically, in research only one analysis is conducted and only one team is involved. That team would use their best judgment in selecting what they believe was the most appropriate way to analyze the data. “However, if that had been done here, that single analysis would be quite misleading.” The researchers in “Many Analysts, One Data Set” concluded:

The observed results from analyzing a complex data set can be highly contingent on justifiable, but subjective, analytic decisions. Uncertainty in interpreting research results is therefore not just a function of statistical power or the use of questionable research practices; it is also a function of the many reasonable decisions that researchers must make in order to conduct the research. This does not mean that analyzing data and drawing research conclusions is a subjective enterprise with no connection to reality. It does mean that many subjective decisions are part of the research process and can affect the outcomes. The best defense against subjectivity in science is to expose it. Transparency in data, methods, and process gives the rest of the community opportunity to see the decisions, question them, offer alternatives, and test these alternatives in further research.

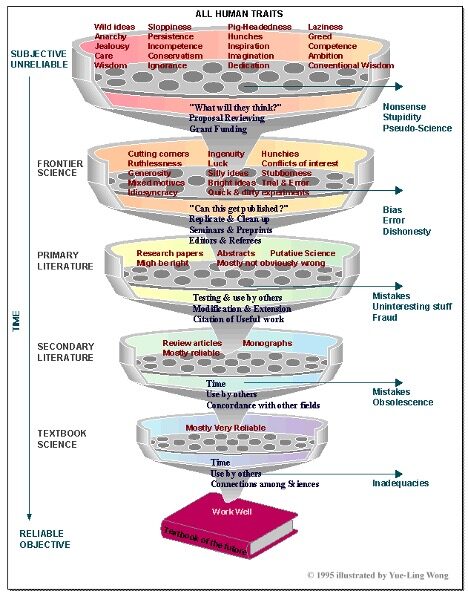

The Knowledge Filter

This research acknowledges that there can be, there will be a subjective factor in scientific investigation. In his discussion of The Knowledge Filter, Henry Bauer said to understand why science may be reliable or unreliable, you have to recognize it is done by human beings, and that “how they interact with one another is absolutely crucial.” Bauer said science gets done through a communal process akin to a filter funnel with several stages. Through this process humans make many, often contradictory, truth claims. With time, this filtering process can transform subjective, unreliable knowledge, into frontier science and eventually into textbook science—which is seemingly reliable and objective.

At the filter of frontier science, researchers do proposal review and grant funding. As this stage, they have to grapple with the question, “What will others think of this?” Through the practice of having colleagues look over grant proposals and manuscripts, “much nonsense, pseudo-science, and stupidity is still-born, or at least filtered out before it’s gotten very far.” Although frontier science is more disciplined than the general intellectual level of society, research at this stage is still a “rather messy business.” Scientists differ in competence, integrity, creativity, interests, judgment patience, etc.

The research presented in “Many Analysts, One Data Set” is an example of primary literature research. The researchers were able to persuade other researchers with the journal Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science that they were on to something and published their work. “So the primary literature of articles in research journals is more disciplined, more objective and less personal than what goes on in individual labs.” But here there can be competing theories and even competing, seemingly contradictory results. Primary literature is not scientific knowledge, it’s just information about certain claims that have been made.

If this information seems interesting enough to other researchers, they may use it in their own studies; testing, modifying, extending, or refuting the initial conclusions. “Whatever survives as useful knowledge gets cited in other articles and eventually in review articles and monographs.” This is the secondary literature, with considerably more agreement and reliability than the primary literature, but it’s far from the “gospel.”

If no more damaging flaws are uncovered, then the knowledge is likely to be put in textbooks. Cleansed of most of the personal bias, error and dishonesty that sometimes occurs in research (see “Reproducibility in Science“), this textbook science is very reliable. But even textbook science isn’t absolute, objective truth (remember, there is no such thing as a “brute,” uninterpreted fact). “While the primary literature in physics is perhaps 90% wrong, textbooks in physics are perhaps 90% right.”

This knowledge filter illustrates that it’s peer review, and the awareness of peer review, and the passage of time that makes scientific knowledge non-subjective and reliable. But there’s nothing automatic about peer review or self-discipline. If peer review is cronyism – if scientists believe it proper to praise their friends and relatives rather than meritorious work irrespective of who does it – then false views and unreliable results will be disseminated.

The wrong conclusion to take from the above discussion is that all scientific investigation is subjective or relative and can’t be trusted. This would lead to chaos and the abrupt halt to the growth of human, scientific knowledge. However, we can and should recognize there are limits to science. In The Limits of Science, Peter Medawar said the most heinous offense a scientist can commit is to declare something to be true when it isn’t. He thought if a scientist couldn’t interpret the phenomenon he was studying, he was obligated to make it possible for another to do so.

Bauer thought the traditionally accepted method of weeding out a small amount of valid, useful information from the “information explosion” of publishing original research should be changed. “We seem to think that more research is always better, and that publishing original research is more worthy than writing review articles or books.” But he asked, why not reward writing review articles and textbooks more than publishing research articles? “Publish or perish” should be changed to “review and refute.”