GLP-1 analog drugs like Ozempic, Wegovy and Mounjaro were originally developed for Type 2 diabetes. They work by activating GLP-1 receptors, which stimulate insulin production. Some of these medications have also been approved for weight loss in obesity by curbing hunger. Then researchers began reporting these drugs also blunted urges for alcohol, opioids, nicotine, and cocaine.

In May of 2023, The Atlantic published, “Did Scientists Accidentally Invent an Anti-addiction Drug?” The article described a woman who thought of herself as having an addictive personality. Her first addiction was alcohol, followed by food and shopping when she got sober. After she began taking Wegovy, her obsessive food thoughts quieted down. She also lost weight.

But most surprisingly, she walked out of Target one day and realized her cart contained only the four things she came to buy. “I’ve never done that before,” she said. The desire to shop had slipped away. The desire to drink, extinguished once, did not rush in as a replacement either. For the first time—perhaps the first time in her whole life—all of her cravings and impulses were gone. It was like a switch had flipped in her brain.

As semaglutides like Ozempic and Wegovy, and their chemical cousin Mounjaro (tirzepatide), have grown in popularity people have reported their benefits extend further than just curbing hunger. They reported a decrease in addictive, compulsive behaviors like drinking, smoking, shopping, biting nails, and even picking at skin. But not everyone on the drugs experiences these positive effects. And, “the long-term impacts of semiglutide, especially on the brain, remain unknown.”

Nature reported a man emailed a neuroscientist after reading her published research on how certain anti-obesity medications seemed to help rats who were addicted to heroin and fentanyl. In the email, he detailed his years-long struggle to kick his addiction to opioids. After reading her research, he’d decided to try quitting again while taking Ozempic. “He said that he was drug- and alcohol-free for the first time in his adult life.”

Stories like this have been spreading fast in the past few years, through online forums, weight-loss clinics and news headlines. They describe people taking diabetes and weight-loss drugs such as semaglutide (also marketed as Wegovy) and tirzepatide (sold as Mounjaro or Zepbound) who find themselves suddenly able to shake long-standing addictions to cigarettes, alcohol and other drugs. And now, clinical data are starting to back them up.

GLP-1 Drugs and the Brain

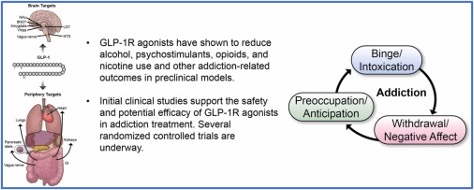

Pharmacological Research published a review in September of 2024 that summarized the available evidence of GLP-1 receptor medications for alcohol and other substance use disorders (ASUD). The review said that human studies suggested there was a relationship between the endogenous GLP-1 system and AUD, alcohol use disorder. Most of these studies were correlational in nature and don’t establish causality. Preliminary human reports, including anecdotal evidence, case-series evidence, and analysis of social media posts “suggest promise for GLP-1R agonists in ASUD treatment.” See the following graphic found in the review.

At this juncture, RCTs [randomized control studies] are very much needed to inform the potential application of GLP-1R agonists for ASUD treatment. In addition to efficacy, results of RCTs will be key to determine the safety profile of GLP-1R agonists in this specific population – an important consideration especially given ASUD comorbidities that could be worsen by exposure to GLP-1R agonists (e.g., malnutrition, pancreatitis). Given that no single medication will work for everyone, it is also important for ongoing and future RCTs to collect comprehensive phenotypic and detailed outcome data to inform which patients are more likely to respond positively to GLP-1R agonists, should these medications prove to alleviate ASUD outcomes. Overall, GLP-1R agonists have shown great promise in preclinical models of addiction, and pending results from clinical studies, could be a compelling addition to the ASUD treatment toolbox.

Hendershot et al published a randomized trial in the February 2025 issue of JAMA Psychiatry that found weekly injections of low-dose semaglutide “can reduce craving and some drinking outcomes.” Nature said there were more than a dozen additional randomized clinical studies testing GLP-1 drugs for addiction now under way worldwide. It seems these weight-loss drugs suppress addiction by acting on hormone receptors in the brain regions that control craving, reward and motivation. They help blunt urges for drugs like alcohol, opioids, nicotine and cocaine through the same brain pathways that also suppress hunger cues and overeating. The research is still in the early stages, and “we first need to find out if it’s efficacious and safe.”

Researchers are already piecing together a picture of how GLP-1 drugs act on the brain’s reward system. They know from animal models that rewarding substances — alcohol, nicotine, opioids, food — activate similar neural circuitry. This links deep brain structures such as the ventral tegmental area, where neurons that synthesize the neurotransmitter dopamine originate, to the nucleus accumbens, where dopamine signals arrive and register as pleasure. Normally, every sip, puff or hit sends a jolt of rewarding dopamine through this circuit, teaching the brain to want more and reinforcing addictive behaviour.

GLP-1 receptors sit on neurons throughout this network and, when triggered, are thought to reduce the flow of dopamine and other chemical messages to make rewarding experiences feel less compelling. When drugs such as semaglutide mimic GLP-1, they blunt the dopamine response and the compulsion to repeat the addictive behaviour fades away.

In July of 2025, Brown University published an interview with an addiction researcher at Brown who is exploring how GLP-1 medications might influence addictive behaviors at the biological level; how they impact cravings. Her lab has been interested in the role hormones play in addiction for some time. She said the basic idea was that appetite hormones, whether they’re for food, alcohol or drugs, “tap into the same craving system in the brain.” Their premise was that environmental triggers like food or a glass of wine activate cravings for the substance. “We started looking at how these hormones, measured in the body, impact brain responses related to craving.”

So now you have this new layer: people who are both addicted and struggling with weight or metabolic issues. And GLP-1 receptor agonists can help on both fronts. Patients may start to feel better physically even before they reach full abstinence. Losing weight, improving liver enzymes, feeling fewer withdrawal symptoms—it all reinforces their sense of progress.

GLP-1 drugs not only target the brain, they can lead to concrete and measurable outcomes people can see; and they are more likely to stay motivated and continue treatment. “You can feel and see it happening in your own body.” The person doesn’t have to rely on a psychiatrist or an addiction therapist to explain the changes happening and keep them motivated to continue treatment. “We’re not just talking about a promising treatment; we’re looking at a potential turning point in addiction psychiatry and public health.”

That so called “turning point” was said to be the FDA’s acceptance that reducing alcohol and drug use is a valid outcome for drug treatment medications. “In the past, a drug for addiction had to show it could lead to total abstinence.” Supposedly this opens the door to more practical, “real-world” treatments for addiction. Yes, it may be that the FDA has indicated it would be receptive to approving a drug to treat AUD that does not lead to total abstinence, but there have been at least two medications doing that off label for a couple of decades.

The End of Addiction?

In 2001, David Sinclair published research In Alcohol and Alcoholism that suggested naltrexone, naloxone, and nalmefene were effective if taken when drinking, but ineffective when used during abstinence. He recommended that naltrexone be taken only when the individual anticipated they would be drinking; and this treatment should continue indefinitely. This became known as the Sinclair Method. It blocks endorphins from being released in the brain when alcohol is consumed, so there is no euphoric experience. In other words, you don’t get the pleasurable feeling from drinking alcohol and as a result drink less.

Over time, your brain learns not to associate alcohol with pleasure, resulting in reduced cravings and improved control over alcohol use. Naltrexone must be taken at least one hour before your first drink.

AUD is reductionistically conceived as a learned behavior by the the Sinclair Method. The “treatment” is contingent upon the person continuing the extinction process. In other words, you need to take the medication an hour before you plan to drink . . . forever. But you can resume drinking for the positive reinforcement of the high simply by not taking your naltrexone before you drink. So, the “treatment” is also contingent upon the motivation level of the potential drinker to take the drug before drinking. This is not a “treatment” for AUD in my way of thinking.

Alcohol in high enough concentrations in the blood stream can cause unconsciousness, stop your breathing leading to cardiac arrest, or inhibit your judgement and self-control. The physiological effects from alcohol in your blood stream continue to occur even if the neurological reward for drinking is neutralized. The Sinclair Method does not stop these other effects from occurring. It simply minimizes the reward from drinking and can gradually extinguish the cravings to drink. It does not metabolize the alcohol in your system. For more information on the Sinclair Method, see “A ‘Cure’ for Alcoholism.”

In 2008 Olivier Ameisen, a French cardiologist, wrote a book titled The End of My Addiction, describing his active drinking and how baclofen helped him stop. Ameisen said he began to struggle with symptoms of alcohol dependence in the 1990s. He had numerous emergency hospitalizations, emergency room visits, detoxifications, and years of both inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation services. He tried Naltrexone and acamprosate, which didn’t stop his cravings or his relapses. He achieved periods of prolonged abstinence, but always struggled with cravings and a preoccupation with alcohol until he discovered baclofen.

He stared using baclofen on March 22,2002 and eventually stabilized his dose at 120 mg per day, with occasional additions of 40 mg as needed to cope with anxiety. At first, he avoided situations and places where alcohol was present. But eventually believed he did not have to be concerned about this. Even when socializing with friends who were drinking, he had no cravings for alcohol. He was encouraged by a friend and physician to write a paper on his self-experiment, which was published in the journal Alcohol and Alcoholism in 2004.

He then wondered if what he was doing made him vulnerable to relapse. So, in May of 2005, sixteen months after he established abstinence with baclofen, he decided to put his recovery to the test. He discovered he could drink alcohol “in a nondependent way.” Occasionally he would have a glass or two of champagne or a mixed drink, but he referred to not drink. In a 2010 article for The Guardian, he said: “I became disease-free.”

Ameisen thought that “In addiction the symptoms ARE the disease.” So, he believed suppressing his symptoms was “curing” his alcoholism. Since he didn’t have cravings and didn’t obsess over alcohol and drinking, he was “cured;” thus the title of his book. But what are the long-term consequences of high-dose baclofen treatment for alcoholism? It isn’t listed as a controlled substance, but there is a baclofen withdrawal syndrome and high dose users are discouraged from rapid tapering or withdrawal. So, is there a slow developing physical dependency or dysregulation of the GABA system in the brain from long term use of baclofen? For more information on Ameisen and baclofen, see “The End of Alcoholism? Part 1 and Part 2.

Neither the Sinclair Method nor baclofen is a “cure” for addiction. If the person stops using them, the cravings and compulsion will likely return with continued drinking. We can expect something similar when using GLP-1 drugs to manage cravings. There is something else we can anticipate with ongoing use of GLP-1 drugs with chemical addictions.

The Guardian reported patients returned to their original weight within 10 months of stopping their GLP-1 drug. “These drugs are very effective at helping you lose weight, but when you stop them, weight regain is much faster than [after stopping] diets.” JAMA Internal Medicine published a post hoc analysis of participants with obesity in November of 2025 that found most participants who experienced weight reduction after a 36-week tizepatide treatment had a 25% or greater weight regain within a year. “These findings underscore the importance of continued obesity treatment.” They also lost their benefits to their cardiovascular health.

Before we start calling GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic, Wegovy and Mounjaro “a potential turning point in addiction psychiatry and public health,” let’s at least do some research to see if their potential holds up in the long-term.