The Hollywood Reporter announced the release of a new documentary, “The Pink Pill: Sex, Drugs & Who Has Control.” It’s about the persistence of Cindy Eckert, the co-founder and chief executive of Sprout Pharmaceuticals who fought for the FDA’s approval of Addyi/flibanserin, a drug that boosts a woman’s sexual desire. Eckert is quoted in the trailer as asking “How do you take on the government for women’s sexual pleasure? You lean right into it and say, ‘This is the conversation we’re going to have.’” But is this just a story of a “David and Goliath battle” to win FDA approval for a drug to boost a woman’s sexual desire?

In “A Pill for Women’s Libido Meets a Cultural Moment,” The New York Times gave a more complex description of the history of flibanserin. Ms. Eckert attended a sexual medicine conference in 2010 where she met Dr. Irwin Goldstein. Dr. Goldstein and he convinced her to watch a series of videos from women who were distraught because they would no longer have access to a treatment they thought improved their sexual desire.

A German company had discovered that flibanserin, originally developed as a treatment for depression, also improved women’s sexual desire. The company then tried to get the FDA to approve flibanserin to treat HSDD, Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder. But the FDA declined to approve it, citing the side effects from the drug. Boehringer Ingelheim, the German company, decided to give up on further trials. Goldstein had been a consultant with Boehringer Ingelheim and showed his recording to various pharmaceutical executives, including Cindy Eckert (né Whitehead) and her then husband, Bob Whitehead, hoping to interest them in flibanserin. “I told them about this amazing drug, it sits on a shelf.”

Goldstein gained prominence after testing Viagra for Pfizer in the 1990s. He was also an advisor to Boehringer Ingelheim on flibanserin research. The Raleigh News & Observer said if flibanserin had been approved in 2010 for women, Goldstein was to have been the principle investigator for developing it for men, “because there is no reason it shouldn’t work in the other gender,” according to Goldstein.

When the FDA rejected flibanserin, the Germans backed out of the project and put flibanserin out for bid. Shortly thereafter, Goldstein, now medical director of sexual medicine at Alvarado Hospital in San Diego, introduced flibanserin to pharmaceutical executives Cindy and Bob Whitehead. At the time, the Whiteheads ran Slate, a Durham company that acquired the rights to flibanserin. They renamed the company, which had moved to Raleigh, Sprout in 2011. Goldstein remains a paid consultant on Sprout’s advisory board.

Interestingly, Slate had produced a testosterone pellet called Testopel that earned a warning letter in 2010 from the FDA for exaggerated marking claims. The FDA claimed Slate’s Web pages and videos misleadingly suggested the drug could improve mood, increase sexual interest and restore erectile function. “Cindy Whitehead said Slate complied with the FDA’s demands and pulled the offending ads.”

The New York Times said at the 2010 sexual medical conference there was also a presentation of a study that demonstrated the difference in brain activity between women with HSDD and women without it. “Ms. Eckert was indignant that, for so long, women’s sexual desire had been dismissed purely as a matter of stress levels and marital woes.” A year later she acquired the rights to flibanserin, founded Sprout Pharmaceuticals, and sought another try at FDA approval, but was unsuccessful.

Clinical trials showed flibanserin slightly increased women’s sexual desire and activity and lowered their distress, compared with placebos, but it also made them drowsy and lowered their blood pressure, particularly when mixed with alcohol. The side effects gave F.D.A. officials pause, and the agency rejected Sprout’s application for approval for the drug, too.

FDA Rejection Not the End for Flibanserin

Typically, being rejected twice by the FDA is a death sentence for new drugs. But with flibanserin, it stimulated a movement of women who thought the rejection was sexist. A feminist activist started an advocacy group focused on flibanserin’s approval called Even the Score, with partial funding from Sprout, as well as women’s groups, consumer organizations and medical societies. Supporters argued there was a double standard with how regulators handled the well-known risks with drugs for men’s sexual dysfunction. The FDA denied the claims of sexism. But support for drug approval increased, as did the opposition to it.

Some feminist and medical organizations thought Even the Score was an example of the creeping influence of pharmaceutical money at the FDA; that the organization was being “bought off” by Sprout. Nevertheless, the FDA approved flibanserin on August 18, 2015 for premenopausal women with HSDD. Regulators required a REMS, a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy, because of serious safety concerns and benefits that were modest, and perhaps even less than modest. Unfortunately, the FDA no longer provides access to flibanserin’s approval announcement.

However, The New England Medical Journal of Medicine published “FDA Approval of Flibanserin—Treating Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder” in January of 2016, where the FDA authors clarified why flibanserin was approved after being rejected twice. The article said the FDA rejected flibanserin the second time because of residual concerns with the benefit-risk profile, and requested additional data that included a study that ensured CNS depression would not affect next-day driving performance.

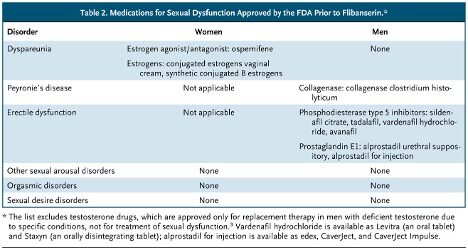

This rejection prompted allegations of gender bias at the FDA, based on erroneous claims that it had approved more than 20 drugs for male sexual dysfunction and none for women. (Those making such assertions included Even the Score, an advocacy campaign partly funded by Sprout Pharmaceuticals, flibanserin’s sponsor after Boehringer Ingelheim sold the rights to the drug.) The FDA rejected these claims and clarified what products had been approved. [see the following table from the article]

After completing the additional studies, Sprout submitted flibanserin for a third review and it was approved 18 to 6. “In general, those recommending approval acknowledged the small treatment effects and substantial safety concerns but considered the unmet medical need.” The approval was contingent upon the inclusion of the inclusion of a REMS beyond labeling.

Not all members of the review team recommended the same regulatory action for flibanserin. Some concluded that its benefit–risk profile was unfavorable, even with the safety measures described here, and recommended against approval. In their view, the observed treatment effects were offset by the potentially life-threatening hypotension, syncope, accidental injuries related to CNS depression, and the unclear clinical significance of a drug-related increase in malignant mammary tumors in female mice. They also questioned the generalizability of the phase 3 safety data to all premenopausal women likely to use flibanserin, given the trials’ extensive exclusion criteria.

The Hastings Center for Bioethics reported in “The Score is Even” that two days after the approval of flibanserin by the FDA, Sprout sold the drug to Valeant Pharmaceuticals for $1 billion. Even the Score’s last post on its website was the day after approval, on August 19th, 2015. The article’s authors said it was sad to see advocacy groups become mouthpieces for pharma; and even sadder when those mouthpieces were feminist groups “that should be protecting the interest of women but instead are protecting a company’s bottom line.” The head of the National Women’s Health Network said, “This decision to approve flibanserin is a triumph of marketing over science.”

Addyi was never a true symbol for gender equity. The drug doesn’t work well and was never safe; because of its dangers, health care providers and pharmacists must be certified to prescribe or dispense the drug. In trials, flibanserin increased “sexually satisfying events” by less than one event a month (an event, by the way, that need include neither an orgasm nor a partner). Its predominant effect may be sedation – each dose is as sedating as four shots of liquor. It interacts dangerously with alcohol and many common drugs, and even on its own can cause precipitous drops in blood pressure and sudden prolonged unconsciousness. Feminists shouldn’t be championing a dangerous, ineffective drug aimed at women.

The New York Times said within a year, Valeant effectively imploded. In 2016, Sprout’s former investors sued Valeant for failing to meet their contractual obligation to market Addyi/flibanserin. In 2018, Valeant returned the drug to Ms. Eckert in exchange for 6 percent of the royalties and “a $25 million loan to help bring Addyi back from the dead.” This year Sprout is on track to double its revenue. And there is also the release of the documentary, “The Pink Pill.”

Since then, the FDA has walked back many of its constraints on Addyi/flibanserin. It removed the REMS and lifted the total ban on alcohol intake for women. This past summer the FDA fast-tracked Sprout’s application to expand approval for postmenopausal women. This persistence led to the FDA’s announcement in December of 2025 it approved the expanded use of Addyi to treat HSDD (hypoactive sexual desire disorder) in women up to the age of 65. But there are still concerns.

Adverse Effects with Flibanserin

In June 2022, “Drug flibanserin—in hypoactive sexual desire disorder” assessed the efficacy and safety of flibanserin. The authors said it has been proposed that flibanserin may enhance sexual desire by reducing serotonergic activity and increasing dopaminergic and noradrenergic activity in the prefrontal cortex, “However, the precise mechanism of action or the treatment of HSDD has yet to be determined.” Flibanserin is a CNS depressant and can cause somnolence (excessive drowsiness) and sedation, increasing the risk of hypotension and syncope (a temporary loss of consciousness or fainting caused by a sudden, brief drop in blood flow to the brain). “Doctors should advise patients taking Flibanserin not to engage in other activities or drive for 6 h after taking the medication.” In conclusion, the article said there was mediocre support: “flibanserin provides some progress, however limited, as a treatment option that may enhance sexual function and outcomes for some women.”

The NIH NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) described flibanserin as the first medication approved by the FDA for the management of HSDD in premenopausal women. It listed the most frequently reported adverse effects, in descending order of frequency, as dizziness, somnolence, nausea, fatigue, insomnia, and dry mouth. Hypotension and syncope can manifest if flibanserin is combined with CNS depressants such as alcohol, opioids, hypnotics and benzodiazepines; or CYP3A4 inhibitors (such as the antibiotics clarithromycin and erythromycin, and some antifungals, antivirals and cardiovascular drugs) in individuals with hepatic impairment (liver problems).

Clinicians or prescribers should commence the moderate or strong CYP3A4 inhibitor 2 days after the last dose of flibanserin. This allows sufficient time for the drug’s clearance from the system, ensuring safe and effective treatment while minimizing the risk of potential drug interactions and adverse effects.

There is a boxed warning on the medication guide for flibanserin, stating: “Your risk of severe low blood pressure and fainting (loss of consciousness) is increased if you take Addyi” if you drink alcohol close to the time you take Addyi. Don’t take Addyi if you’ve had 3 or more alcoholic drinks in the evening. Wait at least 2 hours after drinking 1 or 2 alcoholic drinks before taking Addyi. Don’t take Addyi if you have liver problems.

In August 2020, Ms. Eckert and Sprout received a warning letter from the FDA about a radio ad that failed to disclose all of Addyi’s risk factors. Then in May of 2025, the FDA sent a second warning letter accusing her of doing much the same thing. “As of this week [November 16, 2025 was when the NYT article was written], she still hadn’t taken the post down.” But she is working on another public pressure campaign to expose “a lack of parity in the way insurers cover drugs targeting women’s health conditions versus men’s.” Recall her compliance with the FDA warning letter to Slate about Testopel.

In conclusion, I think Ms. Eckert took rhetorical advantage of feminist ideology to promote and bring Addyi to market. The scientific and medical information noted above for Addyi/flibanserin confirm there are potential adverse effects with the medication that patients should receive guidance on. Her disregard of two FDA warning letters for making “false or misleading claims about the risks associated with Addyi” is disturbing. She may be gambling that another public pressure campaign will enable her to ignore the FDA’s warning letters with impunity. Perhaps it’s because Sprout’s patent exclusivity with Addyi expires on May 9, 2028.

For more information on the initial approval of Addyi by the FDA, see “A Pill for a Mythical Ill” and “Drug Bust.”