The recreational use of marijuana is legal in 24 states and Washington D.C. Forty states also legalized it for medical use. Seven states have decriminalized marijuana use. And since 2024, the DEA has initiated a review to possibly move cannabis from Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act, where it is an illegal substance at the federal level, to Schedule III. And while legalization continues to progress, so does the evidence for the association of marijuana and psychiatric illness.

The Annals of Internal Medicine published a systematic review of almost 100 studies that linked high-THC cannabis products to “unfavorable mental health outcomes, particularly for psychosis or schizophrenia and CUD [cannabis use disorder].” Neuroscience News said the study defined high-THC cannabis products as having THC concentration above 5 mg THC. “The findings reinforce previous conclusions that higher THC concentrations increase the risk for adverse mental health outcomes; however, they fall short of providing the definitive evidence needed to provide clear advice to patients.”

Medpage Today said the research seemed to indicate anxiety and depression worsened in 41% to 53% of the studies, with even higher rates among healthy individuals, those without a co-occurring psychiatric illness. An editorial on the research study quoted one of the researchers as saying while some studies indicated there were therapeutic benefits for anxiety and depression, “many studies detected that use of high concentration cannabis products was associated with adverse outcomes, especially among healthy persons.” THC concentrations have increased since the 1960s from 2-4% to an average of 20% or higher in states where recreational use is legal. “Vaping devices can deliver THC concentrations as high as 70-90%.”

Medscape Medical News said the Annals of Internal Medicine study found high-potency THC products were associated with 75% of participants developing CUD. “The association with psychosis or schizophrenia was identified during the first 12 hours of use and was present at follow-up of up to 2 months.”

In nontherapeutic studies not measuring effects of products on anxiety or pain, study participants experienced worsening anxiety in 53% of the associations and depression in 41% of the associations. Healthy participants — those with no comorbid conditions — were the most prone to these effects.

Critique of Research Findings

Medscape published a commentary article on the Annals of Internal Medicine study, “Weed Potency Is Skyrocketing: Should We Worry?” The author said the group of studies was a “real motley crew” of 42% randomized trials and 40% that were testing whether cannabis products might lead to some benefit for mental health. Just 5% of the studies were rated as having a low risk of bias. “Many studies didn’t adequately report on blinding, didn’t use standard criteria for mental health diagnoses, didn’t adjust for appropriate confounders, and often relied on self-report of cannabis exposure.”

He thought the researchers’ defined cutoff for “high-THC products” was probably below average for the THC products currently available. “But I suspect if they had elected to really push that number higher, they might not have had enough studies to include in the research at all, since truly high-potency stuff is a relatively new phenomenon.” In other words, he thought there were some read flags with the study, suggesting it was due to the research on cannabis being woefully underfunded for over 70 years.

Let me insert some observations here on this author’s critique of the systematic review article in Annals of Internal Medicine, “High-Concentration Delta-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol Cannabis Products and Mental Health Outcomes.” He pointed out an issue with many meta-analysis studies, namely that there wasn’t a common research methodology to all of the studies. Some studies didn’t adequately report on the blinding they did for their study. Others didn’t use “standard criteria for mental health diagnoses” (the DSM-5 or the ICD, the International Classification of Diseases?). And then others didn’t adjust for what he thought were the appropriate confounders.

These aren’t reasons to minimize or disregard the study’s findings, but they do indicate why its findings need further research. Remember, only 5% were rated as having a low risk of bias and cannabis research has been “woefully underfunded” for the past 70 years. But they do suggest how the next stage of research into the association of high-THC products and mental health could be improved.

The term “high-THC products” is an arbitrary definition and could have been set at a higher THC level, say 15 mg THC. But that decision would have only highlighted the mental health concerns with cannabis products with higher than 15 mg of THC in the research. The potential mental health concerns with cannabis products between 5 mg and 15 mg of THC would have been buried in the data. And, how the movement to legalize the use of cannabis has contributed to higher THC levels in cannabis, which has then led to the growing association between cannabis and mental health concerns, would not have been illustrated.

Despite those concerns, the author of “High-Concentration Delta-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol Cannabis Products and Mental Health Outcomes” thought there were some interesting trends in the reported research, particularly with schizophrenia and depression.

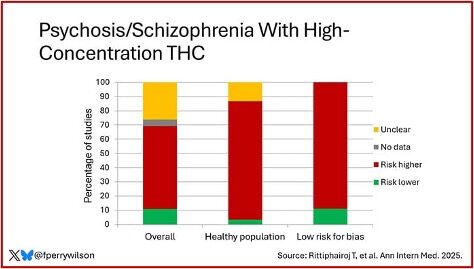

Of the 99 studies in the meta-analysis, 38 had data on psychosis or schizophrenia. “Overall, 58% found a higher risk in the high-THC group, whereas 11% suggested a lower risk in the high-THC group.” The researchers didn’t try to calculate the magnitude of the risk, but he thought they were suggesting higher THC was bad. He pointed out that almost all of the studies that evaluated a healthy population suggested the risk of schizophrenia and psychosis was higher in the high-THC group. Of the studies with low risk of bias, 90% suggested a higher risk in the high-THC group. See the following graph from his article.

While none of the studies compared high- versus low-dose THC, he thought the data suggested THC carried some risk of inducing psychosis; that people at higher risk for psychosis should avoid using cannabis. The data was more mixed for other mental health disorders such as depression.

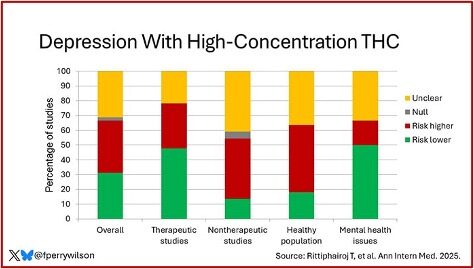

Of the 43 studies that measured depression, 36% found high-dose THC was “unfavorable,” and 31% found it favorable. He thought the results seemed to be driven by the study design. “Studies evaluating the therapeutic potential of THC tended to find less depression with the drug, while studies evaluating the harms tended to find more depression with the drug. Studies in healthy populations tended to link THC to worse depression, but studies in people with mental health issues linked THC to less depression.” See the following graph from his article.

He said he thought the way to interpret the data on depression was that the effects were variable. Some people improved; some worsened. “But I can’t be sure from the data in this study.” Similar to depression, the data for anxiety was variable.

But overall, I’m left not feeling entirely confident that I understand the landscape of risk here. First of all, we already mentioned that the study’s definition of “high-concentration” doesn’t really seem that high, by modern standards. And, of course, concentration isn’t dose. Sure, it’s easier to get a high dose from a product that has a high concentration of THC, but toxicologically, there’s not much difference between eating a “high-concentration” gummy with 10 mg of THC vs two 5-mg gummies.

In times like this, when data are sparse, we need to go back to first principles. And the first principle of toxicology is that the dose makes the poison. So, yes, insofar as THC has any adverse effects, I would be very surprised if they don’t occur more often when higher dosages are used.

Responding to the Critique

He honestly didn’t think there was a clear answer on whether the rapidly increasing potency of THC products presented a major public health problem—yet. Remember his comment that research on cannabis has been woefully underfunded for over 70 years. But there has been regular, serious research into the association of high-dose THC and psychosis that does point to a potential public health problem. Watch this video of a reporter who participated in an “Intravenous THC & CBD Experiment.”

She was given pure THC and a mixture of THC and CBD. On the THC and CBD mixture, the reporter said she seemed flippant; on pure THC, she just didn’t care. The mixture of THC and CBD left her with the giggles: “No matter how hard I tried to take the experiment seriously, it all seems hilarious.” With pure THC, she was suspicious, introverted; “weird.” Every question seemed to have a double meaning. She felt morbid. “It’s like a panic attack.” “It’s horrible. It’s like being at a funeral . . . Worse . . . It’s just so depressing. You want to top [kill] yourself.”

Sir Robin Murray, a leading expert on cannabis and psychosis who over saw this research, said 20 years ago he would tell patients that cannabis was safe. “It’s only after you see all the patients that go psychotic that you realize—it’s not safe.” For more on cannabis and psychosis and Sir Robin Murray’s research, see: “Shatter and Psychosis” and “Cannabis and Psychosis: More Reality Than Satire.”

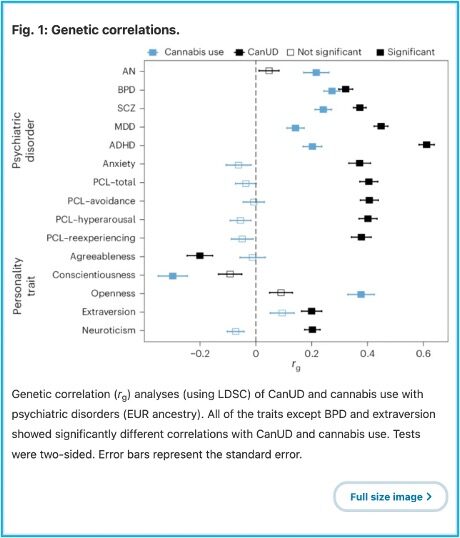

Another recent study by Yale researchers published in Nature Mental Health, “The genetic relationship between cannabis use disorder, cannabis use and psychiatric disorders,” evaluated the relationship between cannabis use and psychiatric disorders. A 2021 report from NSDUH, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health in the U.S., indicated 52.5 million people at least 12 years old reported cannabis use in the past year, and 16.3 million met the criteria for CanUD, cannabis use disorder. Given the large number of users and individuals with CanUD resulting from legalization, understanding the relationship between cannabis use, CanUD and psychiatric disorders is crucial to understanding the broader implications for mental health and well-being.

Cannabis use and CanUD show comorbidity with many psychiatric illnesses, including anxiety disorders, major depressive disorder (MDD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anorexia nervosa (AN), schizophrenia (SCZ), bipolar disorder (BPD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

We live in a time of increasing cannabis availability both for medical applications and for recreational use; an additional secular trend is that cannabis has been increasing in potency. Medical use of a drug usually requires demonstration beforehand of safety and efficacy, but extra-medical considerations have advanced some medical use of cannabis prior to strong evidence for efficacy. And to the contrary, some existing evidence suggests that use of and/or dependence on cannabis may worsen risk for some of the traits it is purported to treat.

The Yale School of Medicine reported researchers in the study analyzed previously published genome-wide association analyses (GWAS) to examine the relationship between CanUD and psychiatric illness. They uncovered several bidirectional causal relationships, with individuals with a psychiatric condition at greater risk of developing CanUD, and those individuals with CanUD at greater risk of developing a psychiatric disorder. See the following figure from Nature Mental Health:

Their results supported previous research that identified bidirectional causal relationships between cannabis use disorder and schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. They also, for the first time, established bidirectional relationships between cannabis use disorder and anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Cannabis is actually approved in most states (41) as a treatment for PTSD, including Pennsylvania and Ohio. The senior researcher of the study said over time, cannabis is more likely to cause PTSD than to treat it. This raises a question about whether a drug that increases the risk of PTSD should reasonably be used as a treatment for PTSD.

With medical marijuana becoming increasingly legalized, many clinicians have been willing to prescribe cannabis for a range of disorders. . . Our study shows that this may not be the best practice. We need randomized clinical trials to show whether cannabis works in order for it to be reasonably considered a medication.

The Importance of the Knowledge Filter

It seems that the cannabis legalization route has taken advantage of cannabis/marijuana being placed in Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act, making it an illegal drug at the federal level. This created serious complications for federally funded research with cannabis. They have published dozens of studies that purportedly show the medical benefits of cannabis, but failed to test their research findings with a scientific knowledge filter. See the discussion of the knowledge filter by Henry Bauer in “Ethics in Science.” Also see “Publish or Perish?” Henry Bauer said in his discussion of the knowledge filter that:

This knowledge filter illustrates that it’s peer review, and the awareness of peer review, and the passage of time that makes scientific knowledge non-subjective and reliable. But there’s nothing automatic about peer review or self-discipline. If peer review is cronyism – if scientists believe it proper to praise their friends and relatives rather than meritorious work irrespective of who does it – then false views and unreliable results will be disseminated.

Contrast this filtering with the popular notion of an “information explosion” that implies a crisis of coping with new knowledge; when rather it’s a matter of weeding out from a mass of rubbish, a small amount of valid, useful, meaningful stuff. This model would suggest a different way of doing things than is now the generally accepted one. We seem to think that more research is always better, and that publishing original research is more worthy than writing review articles or books. But perhaps, given the mass of rubbish that needs filtering, perhaps less research would be better than more?! Maybe writing review articles and textbooks should be rewarded more than producing research articles?!

Some marijuana researchers like Stacie Gruber are concerned that “policy has outpaced science” when it comes to lawmakers making public health decisions about recreational and medical marijuana. See “Marijuana Policy Has Run Ahead of Science.” We need to slow the rush to legalize recreational marijuana and give scientific research time to catch up; and allow the knowledge filter to do its job.