If you’ve heard of a drug called “flysky,” don’t be confused if you google the name and pull up a website for hobbyists interested in radio-controlled (RC) vehicles. Flysky is also the street name for a drug cocktail of opioids like heroin and fentanyl mixed with medetomine, a sedative used in veterinary medicine. Originally found in the illicit drug market in Maryland in 2022, it has been identified in New Jersey, Ohio, California, Colorado, Illinois, and Missouri. And flysky is now available in the Pittsburgh area, according to TribLive: “New street drug ‘flysky’ causes alarm in Western Pa.”

Medetomidine is used as an adulterant or cutting agent, and mixed with opioids to produce a similar effect at less cost to the drug dealer. Many people aren’t aware they’re buying it and don’t seek it out. Additionally, it’s difficult to determine when medetomidine contributes to overdose deaths. While the opioid in the drug cocktail is the main overdose contributor, “What’s harder to know is how much medetomidine is causing overdose deaths.” There isn’t a standard dosage for a flysky drug cocktail.

At UPMC hospitals in Western PA, they were seeing a few cases a month or week. But since an acceleration in March to May of 2025, UPMC Mercy is admitting 2 or 3 patients per day for withdrawal from medetomidine. The medical director for emergency medicine at Allegheny General Hospital (where the hit medical drama series “The Pitt” is filmed) said there’s been a surge of what seems to be medetomidine and related illnesses. “He believes about one patient or so per day or a few per week can be assumed to be undergoing medetomidine withdrawal.” It doesn’t show on a urine drug screen, so it’s hard to know exact data and numbers for medetomidine use.

Atypically for opioid withdrawal, patients will usually be in the ICU for 2 or 3 days because of the severity of the medetomidine withdrawal. Then a patient can be in the hospital a couple more days to be weaned off medications. Medetomidine turns down the adrenaline system in the brain, causing lower heart rate and blood pressure. When people use medetomidine regularly, their body adapts to this lowered adrenaline system. Abruptly stopping flysky use essentially ramps it up dramatically for these drug users and results in withdrawal complications.

This leads to “nausea, vomiting, high blood pressure, confusion or delirium, high heart rate, tremors or shaking, flushing and sweating, plus other symptoms.” The nausea and vomiting can be so serious that people can’t even keep the pills down that could help them. When given Narcan, patients can wake up agitated in various states of withdrawal, “which can be dangerous not only to the patient but to the staff.”

Treatment protocols are still being developed, but UPMC has been using dexmedetomidine, a non-opioid typically used to manage pain and sedation in humans. They want to share their experiences and treatments. “What’s needed is a more rapid way to identify medetomidine and other adulterants sooner in the process.” Prevention Point Pittsburgh, a nonprofit harm organization, offers rapid-test strips that can be used to test a drug for medetomidine. Note the following discussion found in a CDC report that further supports the beneficial response to dexmedetomidine.

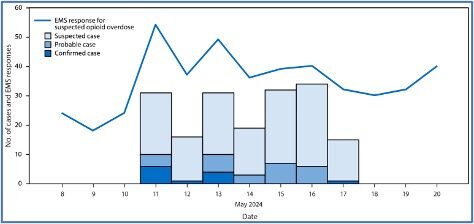

The CDC’s May 2025 MMWR (Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report) described an increase in emergency medical service responses for suspected opioid-involved overdoses with atypical symptoms, mostly clustered on Chicago’s West Side. There were 12 confirmed, 26 probable, and 140 suspected overdoses involving medetomidine mixed with opioids among patients treated at three hospitals in Chicago’s West Side during May 11-17 2024. This was the first time medetomidine was identified in Chicago’s illegal drug supply. Fentanyl was identified in all the drug samples and blood specimens that had medetomidine. See the chart below from the May 2025 MMWR.

The Report said the emergence of medetomidine in the illegal drug supply complicated responses to suspected opioid-involved overdoses and necessitated educating drug users, clinicians, and public health personnel about the adverse effects of medetomidine. Bradycardia (abnormally low heart rate, typically below 60 beats per minute) and hypertensive urgency (significantly elevated blood pressure) were observed frequently in this investigation, and suggested as possible ways to clinically distinguish overdoses of medetomidine mixed with opioids from those involving only opioids.

Addiction medicine and medical toxicology faculty members at three Philadelphia health systems began maintaining a list of patients identified with a newly emerging medetomidine withdrawal syndrome. They reviewed electronic health records of patients admitted to the three health systems during September 1, 2024—January 31, 2025, “whose withdrawal syndrome was characterized by severe signs and symptoms that were not resolved by treatment protocols for fentanyl and xylazine withdrawal.” Overall, 165 patients were identified with one or more signs or symptoms.

Among the 165 patients, 150 (91%) required intensive care unit (ICU) care, including 39 (24%) who received endotracheal intubation [use of an endotracheal tube to keep an airway open]. A total of 137 (83%) patients were treated with and responded to dexmedetomidine infusion, a drug eventually recognized as potentially effective; medetomidine is an enantiomer [Enantiomer molecules are mirror images of each other and are not superimposable (e.g., right and left hands)] of dexmedetomidine, and prolonged dexmedetomidine exposure can induce a withdrawal syndrome manageable with controlled weaning from the drug.

The syndrome described in this report is similar to that described among ICU patients with days-long exposure to dexmedetomidine, an enantiomer of medetomidine, who experience an autonomic withdrawal syndrome with vomiting and agitation when dexmedetomidine is discontinued. In the patients described in this report, these signs and symptoms were not resolved by increasing doses of medications previously effective in managing fentanyl and xylazine withdrawal; however, they were responsive to dexmedetomidine, as described in the management of dexmedetomidine withdrawal. Health care providers and public health agencies need to be aware of this life-threatening withdrawal syndrome because it can require substantial escalations in care compared with the typical opioid and xylazine withdrawal syndromes. Public health agencies should consider testing for medetomidine in their regional drug supplies.

Unique Difficulties with Flysky/Medetomidine

The Conversation said flysky has been linked to at least two overdose deaths in Pennsylvania “and represents a troubling evolution in the continuing opioid crisis.” It emulated the earlier spread of xylazine, known as the “zombie drug” because it causes severe, treatment-resistant skin wounds. Experts estimate it to be 200 to 300 times more potent than xylazine when used as a drug adulterant. This is a win-win situation for dealers. “They can stretch their supply while creating a product that feels stronger and lasts longer than pure opioids alone.”

According to a 2022 DEA report, a kilogram of xylazine powder can be bought from Chinese suppliers for as little as U$6.00 (£4.44). This rock-bottom pricing allows drug traffickers to increase their profit margins significantly while making weak or diluted opioid batches feel more potent to users.

New drug adulterants like medetomidine present unique difficulties for medical professionals and law enforcement. As described above, it makes intoxication and withdrawal symptoms more severe and complicated. It’s not included in routine drug screenings or toxicology tests, leading to its presence often going undetected. It is also metabolized quickly by the body, “making it difficult to track the timing and duration of its effects.”

The case of medetomidine highlights a disturbing reality about modern drug policy: the illicit drug supply continues to change in unpredictable and dangerous ways. Neither medetomidine nor xylazine was developed for human consumption, and there are no human studies examining their drug interactions, lethal doses or safe reversal protocols.

As these veterinary sedatives become more common in street drugs, the challenge for healthcare professionals continues to grow. Traditional overdose response protocols, built around reversing opioid effects with naloxone, become inadequate when faced with multi-drug combinations that affect the body through completely different mechanisms.

Medical and public health professionals need to learn more about the complicated withdrawal effects with medetomidine and opioid cocktails in order to medically treat individuals using them. That is, until the next adulterant comes around. For medetomidine withdrawal guidance for healthcare providers, including periodically updated resources see: Medetomidine on Substance Use Philly or this YouTube webinar, “CDC Medetomidine Webinar for Clinicians. For more information about medetomidine, also see “Medetomidine and Illicit Opioids.” The photo in this article is a screenshot taken from “What is Medetomidine?” by the United States Drug Testing Laboratories (USDTL).