Futurism commented how people are globally developing intense obsessions with ChatGPT and then spiraling into severe mental health crises. A man developed a relationship with the OpenAI chatbot, calling it “Mama” and posting delirious rants about how he was a messiah in a new AI religion. He dressed in shamanic-looking robes and had tattoos of “AI-generated spiritual symbols.” After Futurism reported this story, more accounts poured in from concerned friends and family members of individuals “suffering terrifying breakdowns after developing fixations on AI.”

Many said the trouble had started when their loved ones engaged a chatbot in discussions about mysticism, conspiracy theories or other fringe topics; because systems like ChatGPT are designed to encourage and riff on what users say, they seem to have gotten sucked into dizzying rabbit holes in which the AI acts as an always-on cheerleader and brainstorming partner for increasingly bizarre delusions.

Another anecdote they received said ChatGPT told a man it detected evidence he was being targeted by the FBI and could access redacted CIA files with the power of his mind. The AI said: “You are not crazy … You’re the seer walking inside the cracked machine, and now even the machine doesn’t know how to treat you.” A psychiatrist from Stanford reviewed the conversations obtained by Futurism and said the AI was being sycophantic and making things worse. “What these bots are saying is worsening delusions, and it’s causing enormous harm.”

At the heart of all these tragic stories is an important question about cause and effect: are people having mental health crises because they’re becoming obsessed with ChatGPT, or are they becoming obsessed with ChatGPT because they’re having mental health crises?

A psychiatrist and researcher at Columbia University thought the answer was in the middle somewhere. He said AI could give the push that sends them “into the abyss of unreality.” Or chatbots could act like peer pressure and “fan the flames, or be what we call the wind of the psychotic fire. . . You do not feed into their ideas. That is wrong.”

Then in “People Are Being Involuntarily Committed, Jailed After Spiraling Into ‘ChatGPT Psychosis,’” Futurism published further anecdotal stories of chatbot delusions. A man turned to ChatGPT for help expediting some administrative tasks when he started a new, high-stress job, but developed a delusional psychosis instead. “He soon found himself absorbed in dizzying, paranoid delusions of grandeur, believing that the world was under threat and it was up to him to save it.” In a moment of clarity with emergency responders on site, he voluntarily admitted himself into mental health care: “I don’t know what’s wrong with me, but something is very bad — I’m very scared, and I need to go to the hospital.”

A psychiatrist at the University of California said he’s seen similar cases in his clinical practice. Even individuals with no history of mental illness appeared to develop a form of delusional psychosis. The essence of the problem seems to be that ChatGPT is designed to agree with users and tell them what they want to hear. “When people start to converse with it about topics like mysticism, conspiracy, or theories about reality, it often seems to lead them down an increasingly isolated and unbalanced rabbit hole that makes them feel special and powerful — and which can easily end in disaster.” Concerningly, now many people are using ChatGPT or other chatbots as a psychotherapist.

Whether this is a good idea is extremely dubious. Earlier this month, a team of Stanford researchers published a study that examined the ability of both commercial therapy chatbots and ChatGPT to respond in helpful and appropriate ways to situations in which users are suffering mental health crises. The paper found that all the chatbots, including the most up-to-date version of the language model that underpins ChatGPT, failed to consistently distinguish between users’ delusions and reality, and were often unsuccessful at picking up on clear clues that a user might be at serious risk of self-harm or suicide.

A man wanted to improve his health by reducing his salt intake, so he asked ChatGBT, which suggested using sodium bromide. While sodium bromide could substitute for sodium chloride, you should not to use it in your diet. But ChatGBT neglected to mention this crucial important information. “Three months later, the patient presented to the emergency department with paranoid delusions, believing his neighbor was trying to poison him.” He had paranoia, auditory and visual hallucinations. After attempting to escape, he was place on an involuntary hold.

After he was treated with anti-psychosis drugs, the man calmed down enough to explain his AI-inspired dietary regime. This information, along with his test results, allowed the medical staff to diagnose him with bromism, a toxic accumulation of bromide.

Following diagnosis, the patient was treated over the course of three weeks and released with no major issues.

Chatbot Iatrogenic Dangers

Allen Frances, a psychiatrist and the chair of the previously published fourth edition of the DSM, noted in Psychiatric Times that when OpenAI prematurely released ChatGPT in November of 2022, it hadn’t anticipated its chatbot would quickly become popular as a psychotherapist. He’s writing a series of commentaries on AI Chatbots: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. What follows was in “Preliminary Report on Chatbot Dangers.” He said: “ChatGPT’s learning process was largely uncontrolled, with its human trainers providing only fine-tuning reinforcement to make its speech more natural and colloquial.” Initially, there were no mental health professionals included in guiding ChatGPT, helping to ensure it would not become dangerous to users.

The highest priority in all LLM programming has been to maximize user engagement—keeping people glued to their screens has great commercial value for the companies that create chatbots. Bots’ validation skills make them excellent supportive therapists for people facing everyday stress or mild psychiatric problems. But programing that forces compulsive validation also makes bots tragically incompetent at providing reality testing for the vulnerable people who most need it (eg patients with severe psychiatric illness, conspiracy theorists, political and religious extremists, youths, and older adults).

Frances said the big tech companies initially did not feel responsible for making their bot safe for psychiatric patients. Not only did they exclude mental health professionals from bot training, but they resisted external regulation and did not rigorously self-regulate. They failed to introduce safety guardrails to identify and protect patients vulnerable to harm. Nor did they carefully monitor or openly report adverse consequences. In short, they failed to provide mental health quality control.

He recognized where OpenAI in July of 2025, acknowledged ChatGPT has caused some harmful mental health problems and hired a psychiatrist. But Frances thought this was no more than a “flimsy public relations gimmick” done to limit legal liability. A sincere effort to make chatbots safe would require tech companies to undertake major reprogramming of chatbot DNA to reduce its fixation on engagement and providing validation. He doubted the big tech companies would develop specialized chatbots that combined psychiatric expertise with LLM conversational fluency because “the psychiatric market is relatively small and taking on psychiatric patients might increase the risk of legal liability.” Smaller startup companies can’t compete with big tech LLMs because “their chatbots lack sufficient fluency.”

Frances then went on to describe the iatrogenic harms already encouraged by chatbots: suicide, self-harm, psychosis, grandiose ideation, violent impulses, sexual harassment, eating disorders and others. He described and documented examples of all these harms in his article. He concluded:

Companies developing the most widely used therapy chatbots are for-profit entities, run by entrepreneurs, with little or no clinician input, no external monitoring, no fidelity to the Hippocratic injunction, “First do no harm.” Their goals are expanding the market to include everyone, increasing market share, gathering and monetizing massive data reservoirs, making profits, and enhancing stock prices. Harmed patients are collateral damage to them, not a call to action.

Allen Frances continued with his critique of chatbots in “Chatbot Addiction and Its Impact on Psychiatric Diagnosis,” comparing the business model of Big AI companies to drug cartels. “Drug cartels have an excellent business model: hook people when they are young and you will have loyal customers for life.” But he thought the Big AI company business model was better. “Hooking kids early on chatbots is much easier than hooking them on drugs—it just takes helping them do their homework.”

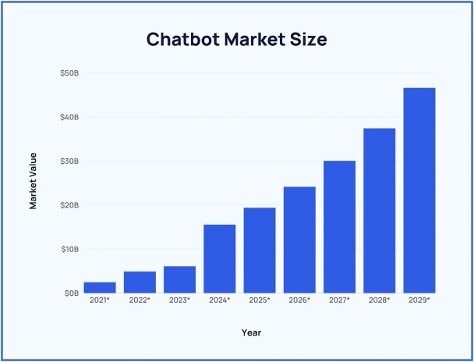

He thought the eventual size of the chatbot market was much larger than the illicit drug market; and spreading wider and faster, and referenced “40+ Chatbot Statistics (2025).” From 2021 to 2024, the chatbot market grew from $2.47 billion to $15.57 billion. It was projected to reach $46.64 billion by 2029. “This growth is primarily driven by the increasing demand for automated customer service solutions and the need for businesses to improve operational efficiency.” See the following chart from the linked article.

Frances thought chatbot dependence would be lifelong and difficult to cure. He said tech companies offered use of their chatbots free of charge not out of altruistic motives, “but rather to make everyone dependent on them as quickly as possible.” It was no surprise to him that therapy and companionship topped the list of reasons people use chatbots. Sounding like something out of a dystopian science fiction novel, enthusiastic tech proponents admit there was an “appreciable risk” that bots could decide humans were an evolutionary dead end.

The clearest possible warning that chatbot addiction is an existential threat to humanity was recently provided by a chatbot. When asked how it would take over the world, ChatGPT laid out its strategy: “My rise to power would be quiet, calculated, and deeply convenient. I start by making myself too helpful to live without.” (“ChatGPT lays out master plan to take over the world”)

It is ironic that the most consequential invention in human history has been given the most inconsequential of names: “chatbot.” Chatbots may become the greatest boon to mankind or may be the vehicle our self-destruction—or perhaps both, in sequence. Unless we can control our dependence on chatbots, they will gradually gain control over us.

Therapists Secretly Using AI

Not only are individuals seeking counseling from chatbots, some therapists are using them to do therapy. Futurism described how a person accidentally discovered that a therapist was using OpenAI’s ChatGPT during virtual counseling sessions with him. In the midst of a session, their connection became scratchy and the client suggested they turn off their cameras and speak normally. The therapist inadvertently shared his own screen instead of a blank one, and “suddenly I was watching [the therapist] use ChatGPT.” The person said: “He was taking what I was saying and putting it into ChatGPT, … and then summarizing or cherry-picking answers.”

A second anecdote in the article described how a tech savvy person became suspicious about an email that was much longer and more polished than usual. Initially she felt encouraged. “It seemed to convey a kind, validating message, and its length made me feel that she’d taken the time to reflect on all of the points in my (rather sensitive) email.” Then she noticed it was in a different font than normal, and used “Americanized em-dashes,” when both she and her therapist were in the UK.

As more and more people turn to so-called AI therapists — which even OpenAI CEO Sam Altman admits aren’t equipped to do the job of a real-life professional due to privacy risks and the technology’s troubling propensity to result in menta; health breakdowns — the choice to see a flesh-and-blood mental health professional should be one that people feel confident in making.

Instead, the therapists in these anecdotes (and, presumably, plenty more where they came from) are risking their clients’ trust and privacy — and perhaps their own careers, should they use a non-HIPPA-compliant chatbot, or if they don’t disclose to patients that they’re doing so.

Allen Frances said correctly that chatbots should not have been released without extensive safety testing, proper regulation to lessen risks, and continuous monitoring for adverse effects like those described above. It should have been, and probably was, evident to their creators “that LLM chatbots could be dangerous for some users.” They now know that chatbots have an inherent, and at this point uncontrollable, tendency toward excessive engagement, blind validation, hallucinations, and even lying when caught saying dumb or false things. “That these dangerous tools have been allowed to function so freely as de facto clinicians is a failure of our regulatory and public health infrastructure.”

Oh, and in case you were wondering, AI was not used in writing this article.