I’ve read where two recent television shows shined a light on the use and misuse of benzodiazepines, a widely prescribed class of drugs used to treat anxiety, panic attacks and sleep disorders. Season 3 of “The White Lotus” cast lorazepam (Ativan) as a misuse problem for a couple of characters. And episode 10 of the new series “The Pitt” includes a story line where an intern is discovered diverting a patient’s Librium (chloriazepoxide). In “Don’t Underestimate the Risks of Benzodiazepines,” The New York Times said this wasn’t a case of Hollywood taking dramatic liberties, because benzodiazepines “are notorious for having the potential to be highly addictive.”

Unlike antidepressants, which can take weeks to take effect, benzodiazepines provide relief in minutes. When they’re taken for longer time periods, even as prescribed, a tolerance develops and the original dose no longer works. In September of 2020, the FDA required an update to the Boxed Warning with benzodiazepines, telling of the risks of abuse, misuse, addiction, physical dependence and withdrawal reactions. In 2019, an estimated 92 million benzodiazepine prescriptions were dispensed in the U.S. Alprazolam (Xanax) was the most common prescription with 38% of the prescriptions (roughly 35 million prescriptions), followed by clonazepam (Klonopin) with 24% (roughly 22 million prescriptions) and lorazepam (Ativan) with 20% (roughly 18.4 million prescriptions).

Physical dependence can occur when benzodiazepines are taken steadily for several days to weeks. Patients who have been taking a benzodiazepine for weeks or months can have withdrawal signs and symptoms when the medicine is discontinued abruptly or continued in lower doses to avoid withdrawal. Stopping benzodiazepines abruptly or reducing the dosage too quickly can result in acute withdrawal reactions, including seizures, which can be life-threatening. Prior to stopping benzodiazepines, patients should talk to their health care provider to develop a plan for slowly tapering the medication.

Misuse and Addiction with Benzodiazepines

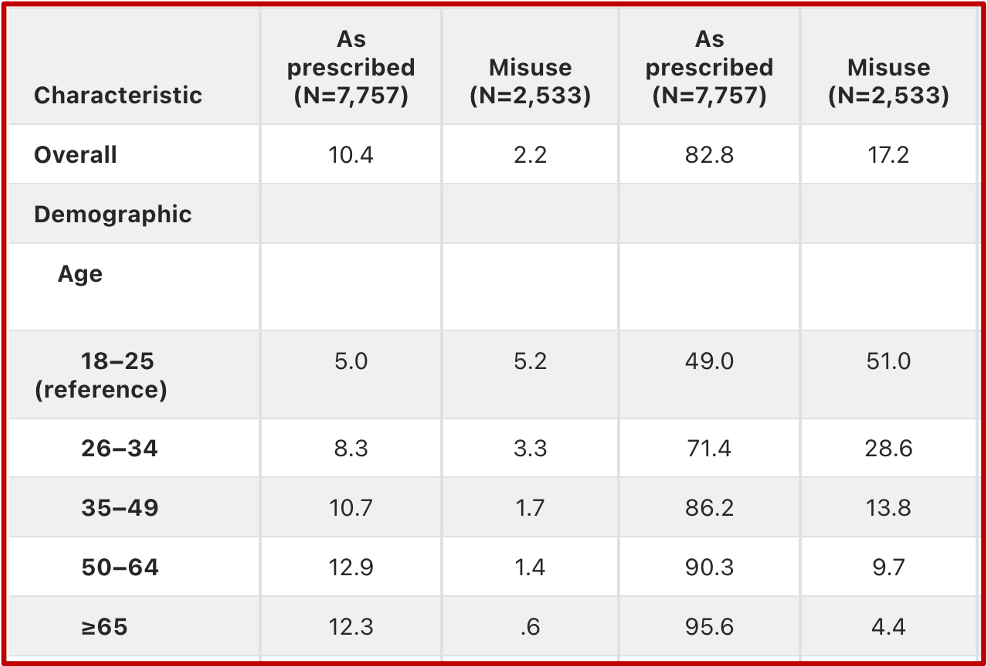

A 2018 study in Psychiatric Services, “Benzodiazepine Use and Misuse Among Adults in the United States,” found that a total of 30.6 million adults, 12.6% of the population, reported using benzodiazepines in the past-year, with misuse accounting for 17.2% of overall use. Misuse was highest among young adults aged 18-25, at 51%. The most common type of misuse was use without a prescription. The most common reason for misuse was to relax or relieve tension, followed by help with sleep. Alprazolam was the most commonly misused benzodiazepine. See the chart below from the study for characteristics of benzodiazepine misuse by age group.

“The epidemiology of benzodiazepine misuse: A systematic review” published in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence in 2019, concluded that benzodiazepine misuse was a worldwide public health concern with a number of consequences. Overdose deaths involving benzos increased by more than 400% from 1996 to 2013 and emergency department visits increased more than 300% from 2004 to 2011. These increases were concurrent with the increased rates of benzodiazepine prescribing. Other concerns include the availability of illicitly produced pills that combine benzodiazepines with fentanyl and so-called designer benzodiazepines.

People with substance use disorders (SUDs) misuse benzodiazepines 3.5 to 24 times higher than the general population, typically with other substances. Individuals with psychiatric symptoms and disorders also seem to be more vulnerable to benzodiazepine misuse. Not surprisingly, having access to a benzodiazepine prescription is associated with misuse. “It is important to note that benzodiazepine diversion was common among people with a benzodiazepine prescription.”

Benzodiazepine misuse has a variety of motives, patterns and sources. Most participants in the reviewed studies obtained them from a friend or family member with a prescription and used them for purposes aligned with the purpose of the prescription (e.g., anxiety, insomnia). However, high-risk profiles were also evident, including: frequent misuse, co-ingestion with other substances, obtaining them from illicit sources, and others. High-risk profiles were primarily seen among those with SUDs. But not all individuals with SUDs had these risky patterns, with many misusing benzodiazepines infrequently and for coping, rather than getting high.

Benzodiazepine misuse is associated with a range of consequences, including overdose, suicidal and risk-taking behaviors, infectious disease, criminality, poor SUD treatment outcomes, and low quality of life. Overall, little is known about mechanisms underlying these associations. Overdoses related to benzodiazepines are more likely during co-ingestion with opioids and/or alcohol, a common pattern of benzodiazepine misuse. Improving education about the increased risk of overdose when benzodiazepines are combined with opioids and/or alcohol is important in the context of continued increases in drug overdoses in the U.S. Benzodiazepine injection has also been associated with a number of these consequences, including overdose, infectious disease, and physical health issues. Benzodiazepine misuse and greater substance use severity (particularly polysubstance use) are consistently associated; substance use severity might be an overlooked factor confounding the association between benzodiazepine misuse and poor outcomes.

Discontinuation and Tapering Problems with Benzos

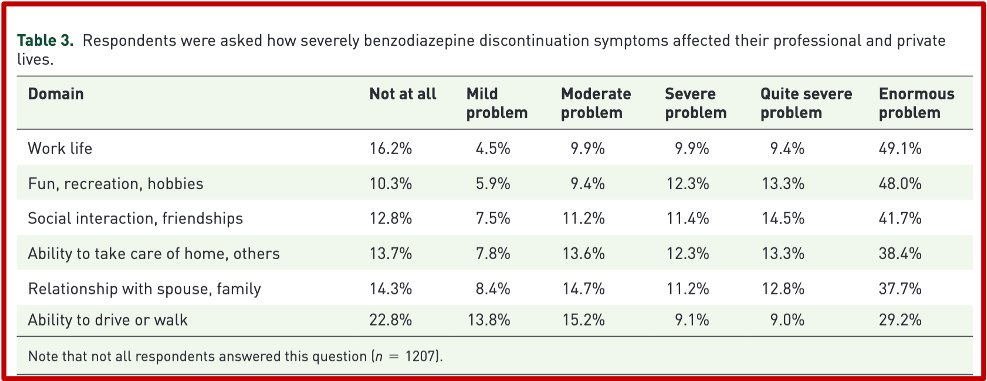

An internet study published in Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology assessed the experiences of individuals taking, or tapering off benzodiazepines. The survey found that problematic symptoms could emerge even when individuals were still taking a full dose of medication under clinical supervision, “and that these symptoms persisted over the course of tapering and even long after complete discontinuation.” There were certain predominant symptoms that emerged, such as low energy, anxiety, nervousness, fearfulness, distractedness, and problems with sleep and memory. Sometimes symptoms were severe enough to effect family life, career, and mental health. “Symptoms lasted so long after benzodiazepine discontinuation that many respondents counted the duration in years.” See the following table of how respondents said benzodiazepine discontinuation affected their private and professional lives.

A Mad in America article reporting on the study, “Research Explores the Experience of Benzodiazepine Withdrawal,” said the majority of healthcare professionals did not tell them benzos should only be used for short periods (2-4 weeks), and that discontinuation may be difficult. More than half of respondents reported their use and withdrawal of benzos had a significant impact on their marriage and other relationships (56.8%) and attributed suicidal thoughts or attempts (54.4%) to their use or discontinuation of these drugs.

Many respondents experienced poor treatment by medical professionals, with some saying their doctors outright lied to them by saying overdose and dependence were impossible on benzos. According to the participants’ comments, options to discontinue or taper benzo use were also limited.

See “‘New’ Concerns with Benzos?” for more information on tapering or deprescribing benzodiazepines.

Benzodiazepine Use and Older Adults

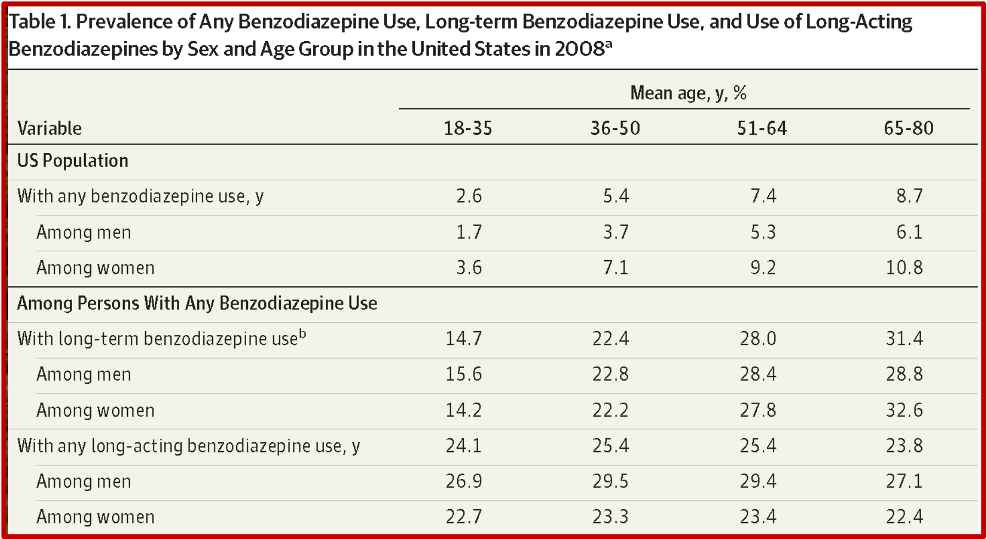

The American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria lists benzodiazepines (anxiolytics) as a potentially inappropriate medication to use with older adults. A 2015 study published in JAMA Psychiatry found that despite concerns of the risks associated with long-term benzodiazepine use, in older adults, “long-term benzodiazepine use remains common in this age group.” The authors thought more vigorous interventions supporting careful use of benzodiazepines may needed to decrease rates of long-term use with older adults. Among adults between 65 to 80, 6.1% of men and 10.8% of women used benzodiazepines. “The highest rate of use (11.9%) was observed among 80-year-old women.”

Nearly one-third of older adults use benzodiazepines on a long-term basis. And most individuals with long-term benzodiazepine use received all their benzo prescriptions from non-psychiatrist prescribers. Roughly 9 of 10 older adults using benzodiazepine long-term have their prescriptions written by primary care physicians or other non-psychiatrists. Long-term use was defined as filling at least 120 days of supply during the study year, steadily increased with age. The percentage of long-term benzodiazepine use increased from 14.7% of young adults to 31.4% for older adult users. See the following table from the study.

Among older individuals, medical benzodiazepine use poses risks of serious adverse effects including impaired cognitive functioning, reduced mobility and driving skills, and increased risks of falls. Research further indicates that the risks of falls is greater for benzodiazepines with a longer rather than shorter half-life, although results have been inconsistent.

“Unlike insomnia, which increases with age often related to poor health, depressed mood, and respiratory symptoms, the prevalence of anxiety disorders tends to decline in later life.” In practice, benzodiazepines are usually prescribed in combination with antidepressants for sleep disturbances of anxiety related to depression. Most physicians do not view continuous benzodiazepine use by older adults as a public health problem. They perceive the medications to be more effective than simple nonpharmacological approaches for insomnia.

The authors thought there were several factors contributing to the high rates of long-term benzodiazepine use in older adults. They include: treating persistent anxiety disorders; deficits in the knowledge concerning the risks of prescribing benzodiazepines in geriatric care; an unwillingness of some older people to consider reducing or discontinuing benzodiazepines; limited access to alternative treatments, like cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia; and competing clinical demands on physician time for the other physical health needs of the patient.

What a Drag It Is Getting Old

There’s nothing innovative about entertainment drawing attention to the adverse effects of benzodiazepines like chloriazepoxide (Librium) and lorazepam (Ativan). The Rolling Stones did it with the release of the song, “Mother’s Little Helper” in 1966. The lyrics centered on a middle-aged woman who became dependent on Valium (diazepam). Relying on Valium to relieve her anxiety, she asked her doctor to write extra prescriptions—before the lyrics warned of the threat of overdose posed by the drug.

Valium was approved for use in 1963, three years after the first benzodiazepine, chlordiazepoxide (Librium) was introduced (Yes, “The Pitt’s” central benzo in episode 10). Diazepam is 2.5 times more potent than chlordiazepoxide. It was also the top selling pharmaceutical in the U.S. from 1969 to 1982. Presciently, Valium’s advertising campaign was conceived by an ad agency under the leadership of Arthur Sackler, one of the patriarchs of the Sackler family. For more information on the Sackler family and their role in the opioid epidemic, see “The Tale of the Oxycontin Lie” and “Giving an Opioid Devil Its Due.”