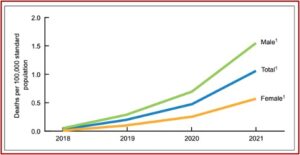

A study published by the CDC , documented a new twist to drug overdose death rates, but it is about a non-opioid veterinary tranquilizer called xylazine. It said xylazine-related overdose deaths in 2021 were 35 times higher than the 2018 rate. The number of drug overdose deaths involving xylazine was 102 in 2018. That rose to 627 in 2019, then 1,499 in 2020 and 3,468 in 2021. Male deaths were double the rates for females over the 2018-2021 period. See the following graph from the study.

An NPR article reported the Biden administration declared illicit xylazine as an emergent threat. Rahul Gupta, the head of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy said this was the first time a substance has been “designated as an emerging threat by any administration.” Known on the streets as tranq or tranq dope, it was first linked to overdose deaths in the North East, around Philadelphia, but has rapidly spread to Southern and Western states. The DEA reported it has seized xylazine and fentanyl mixtures in 48 of 50 states. See “Tranq Dope and Its Consequences.”

The CDC study indicated the rate of overdose deaths involving xylazine was highest in Region 3 (DC, Delaware, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia and West Virginia), followed by Region 1 (Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Vermont) and Region 2 (New Jersey and New York). Between 97.1% and 99.4% of drug overdose deaths involving xylazine also mentioned fentanyl. It has also been co-involved with cocaine, heroin and methamphetamine. See the following map from the CDC study.

Pennsylvania governor Josh Shapiro announced steps his Administration is taking to limit access to xylazine. Among the measures was a notice of intent to temporarily add xylazine to schedule III of Pennsylvania’s Controlled Substance, Drug Device and Cosmetic Act. The Acting Secretary of Health said, “Across the country and here in Pennsylvania we are seeing an alarming increase in the number of overdose deaths in which xylazine was a contributing factor.”

The FDA issued a warning about the risk of xylazine in humans to health care professionals on November 8, 2022. It said xylazine was originally approved in 1972 as a sedative and analgesic for use in veterinary medicine. Its development for use in humans was discontinued because of adverse effects. Structurally, it is similar to clonidine and causes a rapid decrease in the release of norepinephrine and dopamine in the central nervous system. The effects appear similar to that of opioids, making it difficult to distinguish between opioid toxicity and xylazine.

On March 28, 2023, the Combating Illicit Xylazine Act was introduced with bipartisan, bicameral support. The legislation will address a gap in federal law by:

- Classifying its illicit use under Schedule III of the Controlled Substances Act;

- Enabling the DEA to track its manufacturing to ensure it is not diverted to the illicit market;

- Requiring a report on prevalence, risks, and recommendations to best regulate illicit use of xylazine;

- Ensuring all salts and isomers of xylazine are covered when restricting its illicit use;

- Declaring xylazine an emerging drug threat.

Unless you are a veterinarian, own large animals—or are familiar with the drug scene in places like the Kensington area of Philadelphia—you probably have not heard of xylazine before. “Xylazine—Medical and Public Health Imperatives” by Gupta et al in The New England Medical Journal said its first illicit use was reported in Puerto Rico around 2001. It began to appear intermittently in the continental U.A. between 2006 and 2018. The drug’s duration of effect is longer than fentanyl. Using them together enhances the euphoria and analgesia induced by fentanyl and seems to reduce the frequency of injections.

Xylazine is not easily detected by routine toxicology screens, and is likely under-detected and underdiagnosed. It is rapidly eliminated from the body, with a half-life of 23-50 minutes. Individuals with repeated use of xylazine can become physically dependent and experience withdrawal. “When xylazine is stopped abruptly, severe withdrawal symptoms may develop.” There are currently no FDA-approved medications to manage xylazine withdrawal. Repeated use also leads to severe, necrotic ulcerations.

Xylazine causes wounds that erupt with a scaly dead tissue called eschar; untreated, they can lead to amputation. It induces a blackout stupor for hours, rendering users vulnerable to rape and robbery. When people come to, the high from the fentanyl has long since faded and they immediately crave more.

The NYT noted that xylazine can cause wounds so severe that some result in amputation. The article said a 38-year-old tattoo artist known as the Hood Grandma rolled her wheelchair in to the exchange check-in for Prevention Point Philadelphia, a 30-year-old health services center in Kensington, the neighborhood at the ‘epicenter’ of Philadelphia’s drug trade. Her mother, sister and partner all died of overdoses. Last year her right leg had to be amputated because of an infection from tranq bore into the bone. She said, “the tranq dope literally eats your flesh.”

She unrolled a bandage from elbow to palm. Beneath patches of blackened tissue, exposed white tendons and pus, the sheared flesh was hot and red. To stave off xylazine’s excruciating withdrawal, she said, she injects tranq dope several times a day. Fearful that injecting in a fresh site could create a new wound, she reluctantly shoots into her festering forearm.

Another woman developed a dependence on pain killers prescribed after a serious car crash. She began using heroin and eventually fentanyl, chasing the cheaper and more potent high. She watched in horror as the bruises she was accustomed to “from injecting fentanyl began hardening into an armor of crusty, blackened tissue.” People told her everyone’s dope was being cut with something that caused the grisly, painful sores. She said, “I’d wake up in the morning crying because my arms were dying.”

STAT News described how Savage Sisters, a harm reduction group in Philadelphia, has increased how often it offers wound care in the community. The executive director of Savage Sisters said she has been jumping up and down for three years, trying to get attention to the danger of xylazine infiltrating heroin and fentanyl. She said, “what we’re doing is a Band-Aid on a bullet hole.”

Drug users are reluctant to seek help until their medical condition had advanced to a dangerous point. One man waited until the wound on his wrist became so swollen and painful, he couldn’t move his hand. “The hospital told him that if he hadn’t come in then, he would have lost his hand.” Another man who had his wounds cleaned and wrapped was reluctant to consider going to a hospital for more advanced care because he was worried about getting “sick” in the hospital and being unable to use when he begins to experience withdrawal.

At this time, there has been minimal study of the xylazine drug scene. “Experts and advocates are still trying to understand just how dangerous xylazine is and how it works.” While presentations with images of the gruesome wounds from necrosis or dead tissue illustrate the serious adverse health effects from xylazine, medical professionals aren’t even sure what’s causing the necrosis, the wounds. Xylazine-related wounds can be healed with proper care, but many doctors aren’t aware that’s possible. It’s also changing what recovering from an overdose looks like after being given naloxone.

Someone who overdoses on tranq dope might start to breathe again after receiving naloxone, but still be unconscious from the sedative effect of xylaxzine. Giving them another dose of naloxone still won’t wake them up. “When it was just fentanyl, it was more straightforward. . . These kinds of unholy mixtures that bring down the level of consciousness in different ways are really making the overdose response picture tricky.” Although there are protocols for easing someone off illicit opioids, there is nothing for xylazine.

Savage Sisters provides drug users with cards they can give to medical providers that say, “Test me for xylazine.” The card also gives suggestions to medical professionals for treating the symptoms of xylazine withdrawal, which include anxiety. See the graphic below, taken from the STAT article.

It seemed that after fentanyl hit the streets, the drug scene couldn’t get any worse. But then drug entrepreneurs discovered xylazine mixed with fentanyl extends the fentanyl high and is cost-effective. Sure, your arms may feel like they’re dying, like tranq dope is eating your flesh. But isn’t the high worth it?