Now in its 5th edition, the DSM-5-TR, the text revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, was released in March of 2022. This happened to be the first update in almost ten years and it’s selling very well for the APA, the American Psychiatric Association. The paperback version, as well as the hardback and desk reference editions, are the top four best sellers in psychiatry for Amazon. Saul Levin, the CEO and medical director for the APA told Axios that the public has been dying to know more about mental illness. “I think what really caught the imagination was that we’re sitting at home now and looking to say, ‘Boy, I’m feeling depressed — let me now go and find out more about it.'”

It’s hard to tell from this quote if Dr. Levin’s comment was a reflection of APA sales data for impulse buys for the DSM-5-TR, but I doubt it. A quick look at the Amazon prices DSM-5-TR indicates the paperback edition sells for $110.76 and the hardcover for $174.90. The desk reference editions are more affordable at $49.14 and $59.99. A better explanation for its bestselling sales is the fact that psychiatry in the U.S. and increasingly around the world has been dominated by the DSM for the past 70 years. Wired Magazine said this so-called bible for psychiatry is used in prisons, hospitals, and outpatient clinics to diagnose patients, prescribe medications, dictate future treatment and to justify payment for these services.

Axios reported how mental health has gone mainstream, with younger workers demand it as an employee benefit. Ralph Lewis, a Toronto-based psychiatrist, said in Psychology Today that psychiatry is guilty of having oversold its ability to answer the problems of coping with life and regulating one’s emotions and behaviors. Life can be stressful and complicated, leaving people with a feeling they can’t cope. “Many assume that psychiatry has the answers to problems of coping with life and regulating one’s own emotions and behaviors.” The expectations are particularly intense on psychiatrists as medical specialists “who are designated as the ultimate gatekeepers for diagnosis of mental illnesses and, more broadly, mental disorders.”

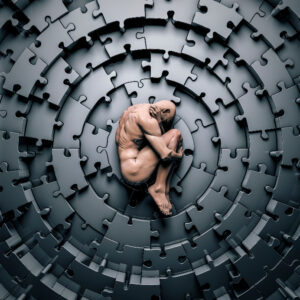

Mental disorders are, by their very nature, difficult to define with specificity. Anxiety and depression are the most common reasons for seeking psychiatric help. There is much confusion among the general public, and even often uncertainty among psychiatrists, as to when to consider these experiences mental disorders: the diagnosis depends on severity, number of associated symptoms, degree of functional impairment, and persistence or recurrence. Unfortunately, psychiatric diagnostic classification systems and mental health awareness campaigns have overgeneralized the definition of mental illness.

Dr. Lewis said the tendency now is to pathologize everyday problems, labeling them as mental disorders. Here he referenced Saving Normal, by Allen Frances, a psychiatrist and the former chair for the DSM-IV. Frances said there should have been cautions in the DSM-IV warning about overdiagnosis and providing tips on how to avoid it. Professional and public conferences, and educational campaigns should have been organized to counteract drug company propaganda.

None of this occurred to anyone at the time. No one dreamed that drug company advertising would explode three years after the publication of the DSM-IV or that there would be the huge epidemics of ADHD, autism, and bipolar disorder—and therefore no one felt any urgency to prevent them. . . We missed the boat.

See “Medieval Alchemy” for more on Allen Frances and Saving Normal.

Dr. Lewis said the COVID-19 pandemic drove up the rates of anxiety, depression and several other mental disorders. Ironically, while the data are complicated, there does not appear to have been much of a rise in the actual rate of mental disorders. What seems to have happened is people’s perception they need psychiatric treatment increased. Although some of the increase represents people now seeking help for significant problems, there is also a phenomenon of these diagnoses being sought.

A diagnosis offers a person an explanation for their difficulties. It lets a person feel understood. It simplifies complexity, helping make sense of things and bringing a bit of order to the inexplicable and chaotic. It provides validation and legitimacy to one’s struggles, as well as sympathy, and it might offer justification for one’s shortcomings or behavioral difficulties. It also confers a sense of identity and group-belonging.

A diagnosis may deliver practical benefits such as sick leave, disability benefits, academic accommodations, and insurance coverage for therapy. Other factors include social media, the internet, and celebrity influence—think about the attention paid to Simone Biles when she withdrew from several events at the 2020 Summer Olympics. And don’t forget about pharmaceutical advertising—just ask your doctor. “In many ways, what we are witnessing is the success of, and unintended consequences of, years of mental health education and destigmatization campaigns.”

Not only does overdiagnosis lead to over-prescribing medications, it also trivializes severe mental illness. The CDC said more than 50% of Americans will be diagnosed with a mental disorder in their lifetime. One in five will experience a mental illness in a given year. “If everyone has a mental disorder, then no one does, and the concept of mental disorder becomes meaningless. It becomes harder for the people most in need of psychiatric services to access the already overloaded system.”

The CDC also stated there was no single cause for mental illness. Early adverse life experiences, the use of alcohol or drugs, feelings of loneliness or isolation as well as biological factors or ongoing chronic medical conditions like cancer or diabetes can contribute to the risk of mental illness. But psychiatry continues to press for the medical model of mental illness and it seems defending the legitimacy of DSM diagnosis goes along with it. This debate has continued without any real movement towards a resolution for the last fifty years.

Dr. Daniel Morehead lamented in “The DSM: Diagnostic Manual or Diabolical Manipulation?” that it would be hard to overstate the torrents of criticism because of the DSM. He said, “The DSM has been, and remains, the centerpiece of contemporary critiques of psychiatry.” Critics of the DSM were wrong. Psychiatry is not at odds with other medical specialties. “Psychiatry differs from them only in the sense that more of the diseases behind psychiatric syndromes lack full explication.”

This is not evidence of its inferiority, according to Morehead, rather it is evidence of the complexity of the human brain. The DSM is “simply the place where clinicians match diseases to treatments through the lens of medical syndromes—just like other doctors.” This seems to be the heart of the debate and the reason for the vigor with which psychiatrists like Dr. Morehead defend the medical basis of psychiatry and psychiatric diagnosis. In another article published around the same time, “Let’s End the Destructive Habit of Doubting Psychiatric Illness,” he said it is time to permanently retire the idea that mental illness may not be fully medical. It is a “pernicious and misleading idea” and he challenged all psychiatrists to no longer tolerate it—publicly or privately.

Dr. Morehead and others appear to recognize that psychiatry is facing an institutional crisis unlike anything it faced since David Rosenhan published “Being Sane in Insane Places” in the journal Science in 1973. Rosenhan has eight “pseudopatients” seek admission to twelve different psychiatric hospitals. Once admitted, they stopped simulating any symptoms of abnormality and waited to see how long it took before they were released. Their length of stay ranged from 7 to 52 days, with an average length of stay at 19 days. None of the pseudopatients were identified as such by hospital staff members; but other patients did.

For more on the Rosenhan study, see “A Censored Story of Psychiatry,” Part 1 and Part 2.

In their book, Psychiatry Under the Influence, Robert Whitaker and Lisa Cosgrove said the trustees of the APA called a meeting shortly after Rosenhan’s article was published. They lamented how the public did not view psychiatry as a medical specialty. The trustees recommended the formation of a task force that would define mental illness and become a preamble to publish the DSM-III. And they made Robert Spitzer the chair of the task force in 1974. Whitaker and Cosgrove said from that beginning, the APA trustees saw how creating a new diagnostic manual could also serve a guild interest.

Remaking psychiatric diagnoses could be part of a larger effort by psychiatry to put forth a new image, which, metaphorically speaking, would emphasize that psychiatrists were doctors, and that they treat real “diseases.”

By adopting the disease model and asserting that psychiatric disorders were illnesses, the APA addressed both its critics and its image problem. Whitaker and Cosgrove said this happened when the organization metaphorically put on a white coat and presented itself as a medical specialty. “This was an image that resonated with the public.” With hindsight, they said, it is easy today to see the ethical peril for the APA that arose when the DSM-III was published. While the APA had devised a new diagnostic manual that helped remake its image, “the peril was that the guild interests might now affect the story it told to the public about the nature of mental disorders, and the efficacy of somatic treatments for them.”

In an interview for Medscape in 2020, the now former chair of the department of Psychiatry at Columbia and former president of the APA, Jeffery Liberman discussed “The Future of Psychiatric Diagnosis” and biomarkers with Melissa Arbuckle, also of Columbia University. She is the vice chair for education and training in the Department of Psychiatry at Columbia. Robert Spitzer, the architect of the DSM-III, was a Professor of Psychiatry at Columbia until his retirement in 2003.

Lieberman acknowledged at the start of the interview there have been no biomarkers identified yet in research. “For the entire history of our discipline, as long as physicians have studied mental illness, we have not had a diagnostic test for it. It’s a clinical diagnosis.” Nevertheless, he has faith that someday there will be a diagnostic test for mental illness: “I do believe that certainly within my professional lifetime, and hopefully sooner rather than later, we will see a diagnostic test.”

The APA self-consciously tied its fate to the DSM in the aftermath of the institutional crisis after the Rosenhan study. It seems to have done so at least partially to affirm itself as a legitimate medical specialty, with the power and authority to prescribe medications. As T. M. Luhrmann noted in Of Two Minds, “psychopharmacology is the great silent dominatrix of contemporary psychiatry.” Prescribing medications is what psychiatrists do that other mental health professionals cannot do. “And as mental health jobs become defined more by their professional specificity, more and more psychiatrists spend more of their time prescribing medication.”

The disease model of mental illness has been a tremendous asset in the fight against stigma and the fight for parity in health care coverage. And it is clear that the disease model captures a good measure of the truth. Mental illness often has an organic quality. People can’t just pull themselves back together when they are hearing voices or contemplating suicide, and their illness is rarely caused by bad parenting alone. Yet to stop at that model, to say that mental illness is nothing but disease, is like saying that an opera is nothing but musical notes. It impoverished us. It impoverishes our sense of human possibility. (Of Two Minds, p. 266)