The number of antidepressant prescriptions written in primary care has continued to increase, and patients are remaining on them for longer durations of time. Yet research into maintaining or discontinuing antidepressants (ADs) in this setting has been almost nonexistent. “Maintenance or Discontinuation of Antidepressants in Primary Care,” published in September of 2021 in The New England Medical Journal, examined the relapse rates of primary care patients who expressed a desire to discontinue their antidepressant. The researchers, G. Lewis and L. Marston et al, found that patients who chose to discontinue their antidepressant therapy had a higher risk of relapse than those who maintained their current medication. However, others believed the results were misleading, because the authors misinterpreted withdrawal effects as relapse.

Lewis, Marston et al found that patients assigned to discontinue their antidepressant medication had a higher frequency of depression relapse than those who maintained their medication through the 52 weeks of follow-up done by the study. Eligible patients were between 18 and 74, and had reported at least two prior episodes of depression. All patients had been receiving and adhering to their daily regimens and had been taking their ADs for more than two years. The main exclusion criterion for the study was current depression. They investigated three SSRIs, fluoxetine (Prozac), citalopram (Celexa) and sertraline (Zoloft), which have similar pharmacologic profiles and similar mechanisms of activity, and mirtazapine (Remeron).

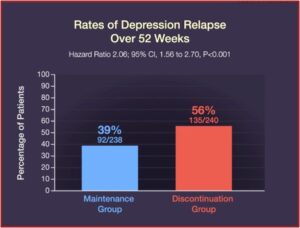

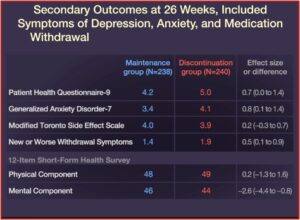

Relapse occurred in 39% of the patients in the maintenance group, while 56% of the patients in the discontinuation group relapsed. Quality-of-life measures and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and medication withdrawal were generally worse in patients who discontinued their ADs. “By the end of the trial, 39% of the patients in the discontinuation group had returned to taking an antidepressant prescribed by their clinician.” See the figures below.

In a critique published in The BMJ of Lewis, Marston et al, Mark Horowitz, Joanna Moncrieff and Beth Parkin said their conclusion that continuing antidepressants reduced the chance of relapse was not warranted. “Because the authors neglected to account for the possibility of antidepressant withdrawal effects being mis-classified as relapse, a fundamental problem in discontinuation trials.” Although the antidepressants were discontinued more slowly than in previous studies, the 8 weeks of discontinuation was still a relatively short taper for patients who had been taking the drugs for more than 2 years. While the approach was consistent with recommendations at the time of the trial (half the dose for one month, then half the dose every second day for one month, before stopping), they are no longer in line with the current guidance from the Royal College of Psychiatrists on Stopping antidepressants.

Antidepressant withdrawal symptoms overlap with most domains of the depression scale used to detect relapse in the study. There was also a high correlation between mean differences on the withdrawal scale and means differences on the depression scale and anxiety scale. “Together, with the overlap of withdrawal symptoms with measures of mood and relapse, this suggests that the withdrawal symptoms may account for the increase in symptom scores and relapse rate.” The reverse would be unlikely, since withdrawal symptoms included physical symptoms that were not intrinsically related to depression—dizziness, electric shocks, and headache. “Occam’s razor would suggest one condition causes several symptoms rather than requiring several conditions.”

Confounding withdrawal with relapse is consistent with the finding that most relapses occurred when withdrawal effects were at their peak, “within 6-12 weeks of when the drugs were stopped (at week 8).” Ninety percent of the total difference in relapse rates between the two arms of the study were present 12 weeks after the drugs were stopped, although this accounts for only 27% of the total follow-up time. Additionally, patients stopping fluoxetine had fewer withdrawal effects than other antidepressants, likely because of its longer elimination half-life. These patients relapsed 25% less than people stopping citalopram and sertraline, “again suggesting withdrawal effects.”

Anxiety and depression scores were the same for both groups at the end of the study. While 44% of the discontinued group had returned to their medication by this time, there was no difference in symptom scores—even with twice as many people on antidepressants in the maintenance group. “This suggests that discontinuation of antidepressants did not worsen mood after the period in which withdrawal symptoms had settled.” There were only small differences in DESS scores (Discontinuation-Emergent Signs and Symptoms) by the end of the 52 week study. Lastly, 71% of the patients in the discontinuation group correctly guessed their allocation to placebo; possibly because of experiencing withdrawal symptoms and then expecting they would get worse.

As there was no effort made to manage the potential confounding of relapse by withdrawal the current study suffers the same flaws as previous discontinuation studies and cannot provide evidence of the benefits of long-term treatment, only the difficulties of stopping it. The authors could resolve some of these concerns by analysing the correlation of withdrawal symptoms with mood scores and relapse amongst individual patients to verify if withdrawal symptoms might account for relapse. They could also re-analyse their data by excluding patients who experienced significant withdrawal symptoms (e.g. modified DESS ≥ 2) from qualifying for a diagnosis of relapse. This would provide a more robust measure of relapse, reducing the potential for the misclassification of relapse as withdrawal. They could also test whether unblinding was associated with relapse.Uncritical interpretation of this study may lead to the erroneous conclusion that antidepressants should be continued to prevent relapse, when in reality all they may be doing is preventing withdrawal symptoms. The more accurate conclusion would be that such symptoms are temporary withdrawal symptoms that can be minimised by stopping the drug more gradually, as recognised by the authors in media interviews, although not in the published paper.

Additional responses in The BMJ supported these points. Bryan Shapiro said, “Dr. Horowitz offers a valid critique of this discontinuation trial—that is, the confounding of illness relapse with antidepressant withdrawal symptoms.” Gary Singh Marlowe said, “For many patients who have been on anti-depressants for more than a few years a 2-month tapering period is insufficient.” Singh Marlowe said practitioners like him have “become increasingly aware that many of the symptoms these patients experience on stopping their anti-depressants are due to the drug withdrawal itself rather than a return of the ‘illness.’” See “Withdrawal Symptoms Cloud Findings of Antidepressant ‘Relapse’ Trial” by Peter Simon on the Mad in America website for more discussion of the Horowitz, Moncrieff and Parkin critique.

Concern that antidepressant withdrawal symptoms are being confounded with relapse symptoms of depression are not just coming from Mad in America and Horowitz, Moncrieff and Parkin. The Mental Elf reported on a systematic review done by the Cochrane Common Mental Health Disorders group on studies where antidepressants were taken for 6 months or more and then discontinued. Relapse rather than discontinuation was the primary outcome for 31 of 33 studies. Only one study reported data on withdrawal symptoms.

All included trials were at high risk of bias. The main limitation of the review is bias due to confounding withdrawal symptoms with symptoms of relapse of depression. Withdrawal symptoms (such as low mood, dizziness) may have an effect on almost every outcome including adverse events, quality of life, social functioning, and severity of illness.

Because of this flaw, the Cochrane group was not able to conclude whether any of the discontinuation strategies were safe and effective, also noting none of them employed tapering protocols beyond a few weeks. The Cochrane authors also doubted the validity of the evidence base for antidepressant continuation, as it depended “on the same and similar studies thoroughly confounded by withdrawal, which is probably mistaken for relapse.”

Consequently, it is unclear to what degree misclassified withdrawal symptoms contributed to “relapse” rates. Research suggests this could pertain to most relapses (El-Mallakh 2012; Greenhouse 1991; Hengartner 2020; Recalt 2019; Rosenbaum 1988). Moreover, withdrawal symptoms may have an effect on almost every outcome including adverse events, quality of life, social functioning, severity of illness, and anxiety and depression scores. For example, low mood and other withdrawal symptoms may register on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) – the prioritised measure for depressive symptoms – and may result in people falsely allocated to having “severe” depressive symptoms.

Based on the review, the Cochrane review authors advised clinicians that:

- Because of confounds, the evidence is unreliable for either discontinuation approach or risk of relapse after discontinuation.

- It is unclear how long antidepressant treatment has to be maintained after remission. Current guidelines are based on consensus rather than evidence.

- Evidence is lacking for appropriate discontinuation approaches for those who do not have “recurrent” depression, the elderly, and those taking antidepressants for anxiety.

- The effect of short tapering regimens (≤ 4 weeks) was similar to abrupt discontinuation. Clinicians should expect to taper much slower, perhaps using liquid drug forms or tapering strips, while closely monitoring for withdrawal symptoms.

- To taper effectively, clinicians will need to recognise withdrawal symptoms. Withdrawal symptoms differ from relapse or recurrence in timing of onset (within days rather than weeks), a rapid reversal after reintroduction of the antidepressant, and the emergence of somatic and psychological symptoms different from the original illness (e.g. shock-like sensations, dizziness, pronounced insomnia). Utilising the Discontinuation-Emergent Signs and Symptoms (DESS) Scale (PDF) may be helpful in monitoring reductions in dosage. When the patient’s DESS score returns to baseline after a reduction, further reduction is appropriate.

- Mark Horowitz, who is a researcher and psychiatrist, was quoted in an article discussing the Cochrane review on Mad in America. He said:

For me, this is such a critical issue both from a personal and a professional perspective. I’m one of the hundreds of thousands of people who have had or are having long, difficult, and harrowing battles coming off long-term depressants because of the severity of the withdrawal effects. And yet, rather than being able to find or access any high-quality evidence or clinical guidance in this situation, I could only find useful information on peer support sites where people who had gone through withdrawal from antidepressants themselves have been forced to become lay experts. Since then, the Royal College of Psychiatrists has taken a great step forward in putting out guidance on Stopping Antidepressants in 2020. However, there is still a lack of research and, therefore, evidence in this area on what works for different people. I want other people to have the evidence base to come off without the same trouble I had.

American psychiatry has fallen behind Britain in protecting its citizens from the potential for iatrogenic harm of antidepressants. In May of 2018, the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Prescribed Drug Dependence published “Antidepressant Dependency and Withdrawal.” At the bottom of the first page is a disclaimer that says this is not an official publication of the House of Commons or the House of Lords. Yet it seems to have influenced the Royal College of Psychiatrists to make public the above linked information for anyone who wants to know more about “Stopping Antidepressants in 2020.”

The Executive Summary of “Antidepressant Dependency Withdrawal” said it was incorrect to view antidepressant withdrawal as largely mild, self-limiting (typically resolving between 1-2 weeks) and of short duration. Available research showed that antidepressant withdrawal reactions are widespread, with incidence rates ranging from 27% to 86%. Nearly half of those experiencing withdrawal described it as severe. Approximately 25% of antidepressant users experienced withdrawal reactions for at least 3 months after cessation; many experienced AD withdrawal for longer than 6 months.

Antidepressants fulfill the criteria for dependency-forming medications within the DSM, the ICD, and the WHO’s definition of dependency. “It is more reasonable to classify antidepressants as potentially dependency-forming medications than not.” Not only do they cause withdrawal in a large proportion of users, there is evidence antidepressants generate tolerance in up to 25% of users. About a third of antidepressant users report being “addicted”, according to their own understanding of the concept.

“The escalation of long-term antidepressant use combined with the misdiagnosis of withdrawal reactions warrants serious concern.” The length of AD use has doubled over the past decade, fueling a rise in prescriptions for the drugs. The evidence suggests this lengthening duration may be partly rooted in “the underestimation of the incidence, severity and duration of AD withdrawal reactions.” This underestimation may have led to many withdrawal reactions being misdiagnosed as relapse or as failure to respond to treatment with AD medications.

There is one final observation to make about the Lewis, Marston et al study. “Maintenance or Discontinuation of Antidepressants in Primary Care,” was of 150 general practices in the United Kingdom, and yet it was published in the prestigious American journal, The New England Journal of Medicine. I wonder if the researchers were attempting to reach a more receptive and less critical audience than if they had published in a prestigious British journal like The BMJ, which did publish the critique of Horowitz, Moncrieff and Parkin.