As 2021 drew to a close, there was another study published online that evaluated ketamine’s value in mental health therapy. As other research has shown, this metanalysis found that ketamine could quickly relieve depression and thoughts of suicide. But the rapid response was usually short-lived. While there was some evidence it helped with other disorders, the evidence base was of a small number of primarily non randomized trials with short follow-up periods, which require confirmation and extension.

The study, “Ketamine for the treatment of mental health and substance use disorders,” was published in the British Journal of Psychiatry Open. The write up of the study in Medical News Today, “What 83 studies say about ketamine and mental health,” was generally positive. However, one of the study’s co-authors thought it was best administered in a clinical environment. In such a setting, people can be provided with “preparation and psychological support during and after the ketamine infusions” which can reduce the risk of adverse events. This is a methodology that follows similar attention to the “set and setting” in psychedelic drug research.

Commenting on the study, Alan Schatzberg, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford, thought the research to date was not enough to determine whether ketamine was effective enough to be worth it. He said, “I haven’t seen enough real data to say that we [have] got a huge winner here.” One of his concerns was that he thought ketamine worked through an opioid mechanism, acting significantly with mu opioid receptors. In certain forms and situations “it’s highly addictive.” Opioid drugs had been used to treat depression until the mid-1950s, but were largely abandoned because of concern about abuse.

Schatzberg was the senior author of a 2018 study in The American Journal of Psychiatry that showed how ketamine activates the opioid system. The study was created after the authors saw research that suggested drugs that only worked on the brain’s glutamate system weren’t very effective antidepressants.

Speaking to NPR about the study, Schatzberg said: “We think ketamine is acting as an opioid. . . That is why you’re getting these rapid effects.” The researchers commented their findings challenged the current understanding of ketamine’s mechanisms of action and its antidepressant properties.

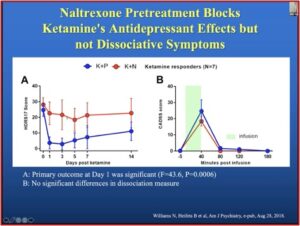

They designed their study to investigate whether ketamine activates mu opioid receptors. This meant they treated patients with depression in two ways. First, depressed patients were given an infusion of ketamine alone. Second, depressed patients were given naltrexone, which blocks the effects of opioid drugs, before they received their infusion of ketamine. This was not a blinded study for ketamine; it is essentially impossible to design a double-blinded study with drugs like ketamine that have dissociative side effects.

An analysis of a dozen patients who got both treatments showed a dramatic difference. Seven of the 12 saw their depression symptoms decrease by at least 50 percent a day after they got ketamine alone. But when they got naltrexone first, there was “virtually no effect.”

Dr. Schatzberg gave a talk on “Clinical Use of Ketamine in Suicide Prevention” for McLean Hospital and discussed the above research. In the slide below, taken from his talk, you see a clear antidepressant effect with the ketamine plus placebo group (K+P). When the same patients get naltrexone first (K+N), there is no evidence of a ketamine effect. The “B” graph shows the dissociative effect of ketamine was not blocked in the ketamine and naltrexone group, while the antidepressant effect was.

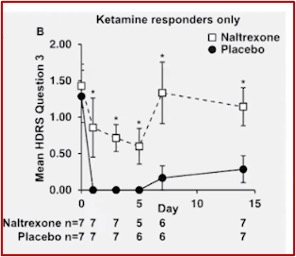

The anti-suicide effects of ketamine were also blocked by naltrexone, as shown in the graph below, taken again from Dr. Schatzberg’s McLean talk. This led the researchers to conclude, “the antidepressant effect of the ketamine is being mediated in some way through mu opioid receptors.”

The anti-suicide effects of ketamine were also blocked by naltrexone, as shown in the graph below, taken again from Dr. Schatzberg’s McLean talk. This led the researchers to conclude, “the antidepressant effect of the ketamine is being mediated in some way through mu opioid receptors.”

Schatzberg noted how there have been five reports since 2018, three of which have been published, all of which show that mu opioid antagonists block ketamine’s behavioral effects. “We can show that ketamine works through an opioid effect.” He then asked, if this effect could be harnessed. In further research, Schatzberg and others looked at buprenorphine, which is a partial mu opioid agonist. At high doses (16-24 mg per day) it has an antagonist effect, blocking typical opioid effects. But very low doses, under 2 mg, have been used to treat refractory depression.

There was a 1995 study by Bodkin and Cole that investigated the potential for low doses (less than 2.0 mg per day) of buprenorphine to treat refractory depression. Its findings suggested a potential role for buprenorphine in treating depression. There was also a 2016 Israeli study by Yovell et al that looked at whether ultra-low doses of buprenorphine (.2 mg-.8 mg) could treat severe suicidal ideation.

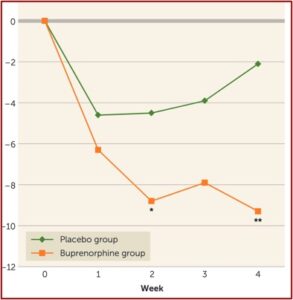

At two weeks, Yovell et al had a dramatic reduction in suicidal ideation as assessed by the Beck Suicide Ideation Scale. This was true at the end of two weeks and at the end of four weeks. At the end of week 4, the buprenorphine was discontinued, reportedly without withdrawal symptoms at a one-week follow-up appointment. “It is possible that in this opioid-naïve population, the short duration and low dosages protected against dependence.” See the graph below taken from the Yovell et al study.

Notice that the dramatic reduction in suicidal ideation was not evident until after one week of ultra-low dose buprenorphine. Contrasting this to the rapid, within one day, antidepressant response noted above, raised a research question Schatzberg and other are currently investigating. Can you get a more immediate anti-suicide effect if you first pre-treat buprenorphine patients with ketamine?

Schatzberg and a team of researchers are looking at 60 patients with major depression and active suicidal behavior. They are repeating the Israeli experiment, but adding it after a ketamine infusion. All patients receive an open label, intravenous infusion of ketamine. Two days later, patients are randomized to receive ultra-low dose buprenorphine or placebo for 4 weeks. This research is ongoing; no results were discussed or presented in Schatzberg’s talk.

Given the previous research, it seems likely these researchers will demonstrate a rapid antidepressive reduction in active suicidal behavior. Combining ketamine and buprenorphine as Schatzberg does in this experiment will simultaneously engage two systems that seem to mediate depression and suicidal ideation—the endogenous opioid system and the glutamatergic system. However, we need to keep in mind that both of the drugs in Schatzberg’s experiment, ketamine and buprenorphine, are classified as Schedule III Controlled Substances.

The Yovell et al study suggested that ultra-low doses of buprenorphine were successfully discontinued without withdrawal. But wasn’t that after a single treatment? Studies of ketamine’s rapid antidepressant effects indicate the changes are temporary and require repeated therapeutic interventions in order to maintain an improvement in mood. In time, could tolerance and withdrawal become evident with ultra-low dose buprenorphine as it has already been shown with ketamine?

Considering the ultimate risk of suicidal ideation leading to completed suicide, it would seem to be an acceptable risk-benefit ratio as a therapeutic intervention for suicidality. But as an ongoing, repeated cycle to treat major depression, the ketamine-buprenorphine combination does not appear to be an acceptable risk to me. In time, the patient could add physical dependency concerns with ketamine and buprenorphine to his ongoing struggle against depression.

I look forward to the completion of Schatberg’s study and hope the publication of the results will address this concern. For more information on ketamine, see this review of research by The Mental Elf and other articles on this website: “Ketamine to the Rescue?”, “In Search of a Disorder for Ketamine,” and “Is Ketamine Really Safe & Non-Toxic?”