By the time she was twenty-three, it had been several years since Judith Grisel had gone twenty-four hours without a drink, pill, fix, or joint. The fun and excitement from using was long gone. “Dying slowly a day at a time was turning out to be unbearably painful.” She’d finally reached the dead end of feeling she was incapable of living either with or without mind-altering substances. But after an unexpected encounter with her father, she decided to go to rehab, became a neuroscientist and eventually wrote a book on the neuroscience and experience of addiction called Never Enough.

In the Introduction of Never Enough, she said there were two factors that motivated her desire to recover. First, she began to wonder what it would be like to be sober. “I promised myself that if I wasn’t less miserable sober than I’d been loaded, I’d go back to using.” Second, she thought she could find a cure. She admitted later on, that in early recovery, she wanted to study addiction so she could use better. “If it’s a disease, and diseases can be cured, and I can cure it, then maybe I can still use.”

But as her knowledge and understanding grew, she discovered she had something to focus on that was not about using. Her growing knowledge about addiction also gave her more compassion for herself and others. She recognized she did not initiate drug use with a blank slate. “I started out with certain tendencies that make drugs for me so valuable and important, that really the courage and perseverance I’ve demonstrated over thirty years, both trying to study this and stay clean and sober, is something that I’m proud of.” She added that character traits that facilitated her addiction—bottomless curiosity, a willingness to take risks, and perseverance—contributed to the successes she’d had as a neuroscientist.

More than anything else, seeking and acquiring knowledge about drugs, addiction, and the brain have given me compassion for the desperate plight of people like me. The understanding I’ve gained has helped me stay clean by informing better choices. My hope is that by illuminating the seeming insanity of colluding in habits that are not only joyless but lethal, this book will contribute to a path of freedom for others.

When Never Enough was first published in 2019, Judith Grisel was interviewed on the NPR program, “Fresh Air.” She said during her interview that she was always interested in the mechanisms of things. She thought if she studied the biological basis of addiction and understood it, perhaps she could “fix” it. She had moments, one after another, of learning things that explained her experiences when using drugs. “There is a common sub strait for all addictions, in neurochemistry in dopamine pathways. And it made perfect sense to me that my dopamine pathways were especially attuned to hear signals from drugs and other things.”

One of the things she learned was that the more you use a drug to change the way you feel, the more your brain produces the exact opposite state. This is the case for every single drug. If you take a drug to feel awake, you will produce lethargy. If you take a drug to feel relaxed, you’ll produce anxiety and tension. A naive user will get a big experience of the drug. “But a regular user feels about normal.”

If you are familiar with 12 Step recovery, you have probably heard the saying; “A drug is a drug, is a drug.” While other recovering addicts are not behavioral neuroscientists like Judith Grisel, they are essentially saying the same thing here. In Never Enough, Grisel said there are three laws in psychopharmacology that apply to all drugs. First, all drugs act by changing the rate of what is already going on in the brain. “They only work by interacting with existing brain structures.”

It follows that drugs can either speed up or slow down ongoing neural activity—and that’s it. Every drug has a chemical structure (a three-dimensional shape) that is complementary to certain structures in the brain and produces its effects by interacting with those structures.

The second law states all drugs have side effects. This happens because drugs do not target specific cells or circuits like neurotransmitters do. Drugs act at all accessible targets, meaning “they act whenever they encounter a receptive structure.” Drugs like nicotine, THC and heroin are called exogenous drugs, meaning they originate outside the body. They work because they mimic endogenous neurotransmitters. Endogenous means they are made inside your body.

For example, the neurotransmitter serotonin modulates mood, cognition, learning, memory, and other physical processes. It is involved with sleep, aggression, sex, and eating. Serotonin targets particular cells at particular times, depending on whether or not it is time to sleep, fight, etc. In contrast, if you take an SSRI, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, it will influence all these behaviors at the same time, producing side effects in addition to potentially influencing your mood.

The third law is particularly important to addiction. It concerns how the brain responds to drugs, not how drugs act on the brain. “The brain is not just a passive recipient of drug actions but responds to the effects of the drugs.” In other words, there is a bidirectional, two-way street kind of relationship between a drug and the brain. “Repeated administration of any drug that influences brain activity leads the brain to adapt in order to compensate for the changes associated with the drug.” This is called adaptation.

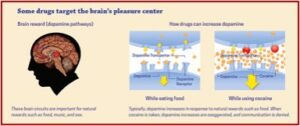

For the brain, the difference between normal rewards and drug rewards is like the difference between someone whispering into your ear and someone shouting into a microphone. Just as we turn down the volume on a radio that is too loud, the brain of someone who misuses drugs adjusts by producing fewer neurotransmitters in the reward circuit, or by reducing the number of receptors that can receive signals. As a result, the person’s ability to experience pleasure from naturally rewarding (i.e., reinforcing) activities is also reduced. See the following illustration.

This reduction of receptors takes time to return to a pre-drug use homeostasis and in some cases may not be able to return completely. That is why a person who misuses drugs eventually feels flat, without motivation, lifeless, or depressed; they are unable to enjoy things that used to be pleasurable for them. Now, the person needs to keep making drugs to feel normal or experience a normal level of reward—which only makes the problem worse. The person will also need to take larger amounts of the drug to produce their high—an effect known as tolerance. Getting high is increasingly short-lived; and the purpose in using becomes to put off withdrawal.

This reduction of receptors takes time to return to a pre-drug use homeostasis and in some cases may not be able to return completely. That is why a person who misuses drugs eventually feels flat, without motivation, lifeless, or depressed; they are unable to enjoy things that used to be pleasurable for them. Now, the person needs to keep making drugs to feel normal or experience a normal level of reward—which only makes the problem worse. The person will also need to take larger amounts of the drug to produce their high—an effect known as tolerance. Getting high is increasingly short-lived; and the purpose in using becomes to put off withdrawal.

The terrible truth for all those who love mind-altering chemicals is that if the chemicals are used with regularity, the brain always adapts to compensate. . . . The brain’s response to a drug is always to facilitate the opposite state; therefore, the only way for any regular user to feel normal is to take the drug. Getting high, if it occurs at all, is increasingly short-lived, and so the purpose of using becomes to stave off withdrawal.

This maxim applies to every effect of any drug that impacts the brain. At first, drugs produce good feelings because when they reach the brain, they impact the nucleus accumbens and other brain structures related to experiencing pleasure. But the brain is designed to return to its homeostatic “set point.” So, it counteracts the flood of dopamine released by the drug, which is interpreted as pleasure or the possibility of pleasure.

This is the driving force and curse of regular drug users. It results in an urge to use and reinforces the destructive cycle that underlies habitual drug use. With repeated exposure to the same stimulus over time, there are smaller and smaller changes in dopamine. Eventually, there is essentially no change in mesolimbic dopamine when exposed to a favored drug. But withholding it leads to a big drop in dopamine levels, which we experience as “a feeling of disappointment and craving.” The disappointment and craving experience anticipates that withdrawal is not far behind. Ultimately, according to Grisel, the most profound law of drug use is there is no free lunch. Also see: “Never Enough and Adaptation.”