Did you know that millions of children in the US have been diagnosed with ADHD? The CDC said in “Data and Statistics About ADHD,” that the number of US children diagnosed with ADHD increased from 4.4 million in 2003 to 6.4 million in 2011. It decreased to 6.1 million in 2016. Sixty-two percent of the children diagnosed with ADHD are taking medication. And yet, the prominent Harvard psychologist Jerome Kagan believes ADHD is an invention.

Kagan made this claim in a 2012 interview with Spiegel, when he was asked if he was saying ADHD was just an invention, he said: “That’s correct; it is an invention.” Every child who does not do well in school is sent to a pediatrician who then says: “It’s ADHD; here’s Ritalin.” The neurologist Steven Novella said in “The ADHD Controversy,” that such a characterization was irresponsible. He acknowledged the fact that ADHD is a fuzzy clinical entity, but said progress has been made in understanding what is happening in the brains of most people with ADHD.

The current consensus is that ADHD is a deficit of executive functions. The frontal lobes carry out many critical functions, some considered executive functions: they include being able to focus your attention, maintain focus, switch among tasks, filter out distractions, and impulse control. Executive function includes the ability to weigh the probable outcomes of your behavior and then make high-level decisions about how you will behave.

He went on to say that convergent data from neuroimaging, neuropsychology, genetics and neurochemical studies point to the involvement of a part of the brain known as the frontostriatal network contributing to the pathophysiology of ADHD. “At this point there is no reasonable disagreement about the fact that ADHD is a disorder of brain function.” He referred to an article by David Tuller, whose concerns were more nuanced than Kagan’s. Tuller interviewed Richard Scheffler, co- author of The ADHD Explosion with Stephen Hinshaw. He said the issue was a spike in ADHD diagnoses, not that ADHD was an invented disease.

ADHD is real—it’s not made up. But it exists on a continuum. There’s no marker or white line that says you’re in the “definite” or “highly likely” group. There’s almost unanimous agreement that five or six percent clearly have enough of these symptoms for an ADHD diagnosis. Then there’s the next group, where the diagnosis is more of a judgment call, and for these kids, behavioral therapy might work. And then there’s a third group, on the borderline. These are the ones we’re worried about being pushed into an inaccurate diagnosis.

Scheffler said the research done for their book found that in general, there was a relationship between the rates of ADHD diagnoses and changes in the 1990s with how many states budgeted schools. Money was provided based upon the number of students making positive movement towards performance measures like graduation rates and test scores. Then in the early 2000s, President Bush tied federal dollars to the same kind of budgeting for performance. “We were able to show that these moves were highly correlated with spikes in various states in the diagnosis of ADHD.”

In an opinion article for The New York Times, Hinshaw and Scheffler said that unless we were careful, we faced an epidemic of 4- and 5-year-olds being wrongfully told they have ADHD. Their research showed skyrocketing ADHD diagnoses, especially among the nation’s poorest children. Their research data seems to reflect that reported above in the first paragraph by the CDC in “Data and Statistics About ADHD.”

For example, we found that in public schools, A.D.H.D. diagnoses of kids within 200 percent of the federal poverty level jumped 59 percent after accountability legislation passed, compared with under 10 percent for middle- and high-income children. There was no such trend in private schools, which are not subject to legislation like this.

By the age of 17, nearly one in five American boys and one in ten girls will be told they have ADHD. This is a 40 percent increase over the last ten years and double the rate of 25 years ago. They see this leading to more prescriptions despite the guidance from organizations like the American Academy of Pediatrics that behavioral therapy, not medication, should be the first-line treatment for children under 6. Accurate diagnosis requires reports of impairment from home and school, and a thorough child and family history to rule out abuse or unrelated disorders. “Too many kids are identified and treated after an initial pediatric visit of 20 minutes or even less.”

The CDC data indicated 77% of the children diagnosed with ADHD between the ages of 2 and 17 were receiving treatment. Thirty percent were treated with medication alone; 15% received behavioral treatment alone; and 32% received both. Around 23% were receiving neither medication nor behavioral treatment. approximately 5 in 10 children with ADHD also had a behavior or conduct problem; 3 in 10 with ADHD had anxiety. Seventeen percent were said to be depressed and 14% had autism spectrum disorder.

So there seems to be a problem with accurate diagnosis and overdiagnosis of ADHD leading to medication treatment. What are the implications of these diagnostic problems? And what are the long-term consequences for the children who are medicated?

A Norwegian article, “Drug Treatment of ADHD—tenuous scientific basis,” said that recent systematic reviews indicated there was a weak evidence base for the use of methylphenidate (Ritalin, Concerta) when treating children and adolescents with an ADHD diagnosis. The authors began with an examination of the MTA study (Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD), stating it was crucial to understanding the current state of knowledge on ADHD treatment. The MTA study showed a reduction in ADHD symptoms in the medication groups at 14 months. But that significance disappeared over the next two years.

After six years, participants in the MTA study who received behavioral therapy but no medication had lower rates of anxiety and depression. The latest results were published in 2017, 16 years after the start of the study. After evaluating the data, the conclusion of the researchers was that the long-term use of central nervous system stimulants was associated with a suppression of adult height, on the average of 1-2 cm. But there was no reduction in ADHD symptoms.

There is no doubt that children with ADHD have genuine and serious problems. However, we cannot ignore the fact that research has yielded only weak evidence to support the extensive use of medication that occurs today. This state of affairs should trigger renewed public and expert discussion on the pharmacological treatment of ADHD in children and adolescents.

There was a further investigation of participants in the MTA study, this time of adolescents and young adults without childhood ADHD: “Late-Onset ADHD Reconsidered.” The purpose of the study was to investigate an influx of adolescents and young adults who present at clinics with complaints of inattention and/or hyperactivity/impulsivity complaints and inquire about stimulant medication. “It remains unclear whether this trend is driven by typically developing individuals seeking stimulant medication for cognitive enhancement or by individuals with late-onset ADHD that warrants medical treatment.” The results indicated that when assessing adolescents and young adults for first-time ADHD diagnoses, clinicians should obtain a thorough psychiatric history and assessment of current functioning.

After using a diagnostic procedure that considered multi-informant data, longitudinal symptoms patterns from childhood to adulthood, Co-occurring mental disorders and substance use, 95% of the individuals who originally screened positive for late-onset ADHD were excluded from diagnosis. When assessing adolescents and young adults for first-time ADHD, 53% of adolescents and 83% of adults who met all the late-onset criteria for ADHD were excluded because their symptoms “were better explained by heavy substance use or another mental disorder.”

SAMHSA, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, noted in “Adults with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Substance Use Disorders” studies that have found adults with ADHD are more likely than their peers without ADHD to develop a substance use disorder (SUD) sometime in their lives. One large epidemiological study found that 15.2% of adults with ADHD also met the criteria for an SUD, compared to 5.6% of adults without ADHD. Research has also indicated that as the severity of ADHD increases, so may the SUD risk. “In a recent analysis of data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, each additional ADHD symptom before age 18 was associated with a greater lifetime chance of developing substance dependence.”

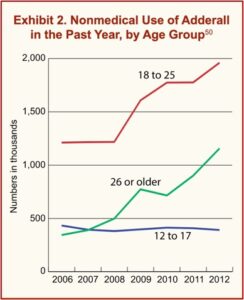

Much of the research into the misuse of prescribed stimulants has been with college students. College students were found to misuse Dexedrine and Adderall more than other prescribed stimulants. According to the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, the nonmedical use of Dexedrine and Adderall has risen among college-aged adults and adults 26 and older. Between 4 and 20 percent of college students have used a prescription stimulant without having a legitimate prescription in the past year, typically obtaining the medication from friends who either sell or give their medications away. “Roughly a third of college students with ADHD report that they have sold or given away their medication at least once.” See the following chart.

So, what are the risks with ADHD medications? There are problems with diagnosis and concerns of overdiagnosis, particularly with poor children (See “Demolishing ADHD Diagnosis”). After 2 or 3 years the positive effects of ADHD medications seem to disappear. Long-term use seems related to a suppression of adult height. There appears to be an association between ADHD and an increased risk of SUD. At least one study concluded there is weak evidence for the use of Ritalin and Concerta when treating children and adolescents with an ADHD diagnosis. ADHD was said to be a “fuzzy clinical entity” by a neurologist who believes ADHD is a disorder of brain function.

So, what are the risks with ADHD medications? There are problems with diagnosis and concerns of overdiagnosis, particularly with poor children (See “Demolishing ADHD Diagnosis”). After 2 or 3 years the positive effects of ADHD medications seem to disappear. Long-term use seems related to a suppression of adult height. There appears to be an association between ADHD and an increased risk of SUD. At least one study concluded there is weak evidence for the use of Ritalin and Concerta when treating children and adolescents with an ADHD diagnosis. ADHD was said to be a “fuzzy clinical entity” by a neurologist who believes ADHD is a disorder of brain function.

Web MD said the side effects and risks from long-term use of ADHD medication include: heart disease, high blood pressure, seizure, irregular heartbeat, abuse and addiction, and skin discolorations. Although it’s rare, ADHD medications may be tied to mental health issues like aggression and hostility; and some say they developed symptoms of bipolar disorder. “The FDA has also warned that there’s a slight risk that stimulant ADHD drugs could lead to mood swings or symptoms of psychosis—like hearing things and paranoia.”