Antipsychotic treatment is often associated with weight gain and metabolic syndrome, a cluster of symptoms that increases the risk of heart disease, stroke and diabetes, independent of other adverse effects like sexual dysfunction, drowsiness, dizziness, restlessness, and others. In The Lancet, Pillinger et al compared and ranked 18 antipsychotics on the basis of their metabolic side-effects. They found that antipsychotics varied widely in their effects on body weight, BMI, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and glucose concentrations. Olanzapine (Zyprexa) and clozapine (Clozaril) were ranked the worst for metabolic-related adverse effects, while ironically being identified as among the most effective antipsychotic drugs. Aripiprazole (Abilify, Aristada), brexpiprazole (Rexulti), cariprazine (Vraylar), lurasidone (Latuda), and ziprasidone (Geodon) were the most benign profiles.

In the same issue of The Lancet, Yoav Domany and Mark Weiser compared the results of this study with a network meta-analysis on the efficacy and adverse effects of antipsychotics. Clozapine was the most efficacious in reducing overall symptoms and amisulpride (Solian) was the most efficacious in reducing positive symptoms. “One would hope that data on efficacy and adverse events could be taken together with the detailed information on metabolic adverse events from this study to consider a personalized medicine approach in treating patients with schizophrenia.”

This approach could be part of a shared decision-making process, based on a discussion with the patient weighing the benefits and disadvantages of each treatment option. Such an approach is hampered by the fact that clozapine and olanzapine, which consistently come out among the best in terms of efficacy, are also consistently associated with the highest rates of metabolic adverse effects, hindering such a process at this stage.

One limitation of the Pillinger et al study was the studies in its meta-analysis were quite short, in the range of 2-13 weeks. The authors noted how randomized controlled trials are generally short and recommended that future studies should “examine antipsychotic-induced metabolic dysregulation in patients receiving long-term maintenance therapy.” Further, lifestyle and treatment factors (physical comorbidity, alcohol use, smoking, diet, exercise, and co-prescription of psychiatric—eg, mood stabilisers—or physical health medications—eg, statins or anti-glycaemic drugs) may have influenced metabolic outcomes. “Treatment guidelines should be updated to reflect differences in metabolic risk, but the choice of the treatment intervention should be made on an individual patient basis, considering the clinical circumstances and preferences of patients, carers, and clinicians.”

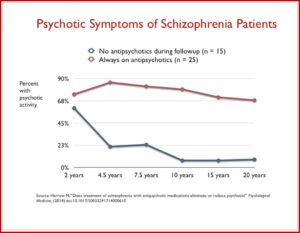

Standard treatment guidelines are that antipsychotic medications should continue indefinitely after someone has experienced more than one psychotic episode. But according to Sandra Steingard, there is less agreement treatment guidelines after a single psychotic episode. “Current guidelines recommend drug treatment for two to five years, the idea being that if a person remains well during that time, it might then be safe to stop the drug.” She said most psychiatrists assumed that by reducing risk of relapse you would improve long-term outcomes. But that assumption may not be correct. Not only are there risks of weight gain and tardive dyskinesia, antipsychotics seem to impair functional outcome. Robert Whitaker reported that Martin Harrow and Thomas Jobe did a long-term study of 200 psychotic patients. Patients who were off medication had better cognitive functioning and lower levels of anxiety than medicated patients. Patients on medication were more likely to be psychotic at follow-up. “Eighty-six percent of the medication-compliant patients were psychotic at the 4.5-year follow-up, compared to 21% of those who had stayed off antipsychotics. This dramatic difference remained throughout the study.” See the following chart.

Harrow also found that once patients who went off medication were stable, they were likely to remain stable for extended time periods. None of the stable, off-med patients stable at the 7.5-year follow-up relapsed in the next 7.5 years. Seventy to 90% of the unmedicated patients were working more than half time, compared to roughly 25% of the medicated patients. Those with milder disorders who continued taking medications had worse outcomes than schizophrenia patients who were off their medications.

Harrow also found that once patients who went off medication were stable, they were likely to remain stable for extended time periods. None of the stable, off-med patients stable at the 7.5-year follow-up relapsed in the next 7.5 years. Seventy to 90% of the unmedicated patients were working more than half time, compared to roughly 25% of the medicated patients. Those with milder disorders who continued taking medications had worse outcomes than schizophrenia patients who were off their medications.

Harrow discovered that patients off medication regularly recovered from their psychotic symptoms over time (2-year to 4.5-year outcomes), and that once this happened, they had very low relapse rates. At the same time, a majority of the patients on medication regularly remained psychotic, and even those who did recover often relapsed. Harrow’s results provide a clear picture of how antipsychotics worsen psychotic symptoms over the long term.

Schizophrenia monotherapy treatment is not always effective, and some individuals receive additional interventions, such as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and psychological therapies. Ortiz-Orendain and others conducted a Cochrane review that compared antipsychotic monotherapy and combined treatment. The authors found low-quality evidence that combined antipsychotics improved the clinical response. The study indicated that more people who received combination therapy showed an improvement in symptoms. But there were no clear differences with other outcomes, such as relapse, hospitalization, adverse events, discontinuing treatment or leaving the study early. In her review of the Ortiz-Orendain et al study for The Mental Elf, Elena Marcus said it was a well conducted systematic review. However,

One of the main limitations of this review lies in the quality of included studies, with outcomes rated as low or very low quality which really questions our confidence in the reported estimates. There was a particularly high or unclear risk of reporting bias and attrition bias across studies and as authors included quasi-randomised trials there was a risk of selection bias in ~70% of studies. Whilst five studies were clearly quasi-randomised, for 39 studies there was not enough information to judge whether sequence generation was truly random, so the risk of bias here was unclear rather than high.

Users of antipsychotic medications also describe a distinctive experience, characterized by sedation, cognitive impairment, emotional blunting and reduced motivation. These are in addition to the various physical effects, including weight gain, sexual dysfunction and neurological consequences. Thompson et al described a synthesis of qualitative data about mental and behavioral changes associated with taking antipsychotics, and how these interact with symptoms of psychosis and people’s sense of self and agency. They found that neuroleptics interfered with people’s ability to carry out basic activities. But they also reduced the intensity of intrusive psychotic experiences and other symptoms, such as anxiety and insomnia.

Anything that changes our mental faculties is likely to impact on our sense of ourselves, and this is a common experience in relation to mood or experience-modifying agents. In the studies we reviewed, some participants felt neuroleptic-induced effects deprived them of important aspects of their personality; their drives, imagination or humour, for example. Others felt that by reducing the symptoms of psychosis, the drugs were able to restore them to a state in which they felt ‘themselves’ again. Similarly, some people were content to view themselves as having a disease requiring ongoing treatment, while others felt that taking neuroleptic medication symbolised a tainted identity. Schizophrenia or psychosis can disrupt people’s sense of self, and studies of personal recovery have described the importance of reconstructing a sense of self in a way that is distinct from symptom improvement. Therefore, although neuroleptics may effectively suppress symptoms, their effects can nevertheless be experienced as detrimental to sense of self and identity, with important implications for social functioning and achievement of life goals.

John Read and Ann Sacia of the University of East London surveyed 650 individual’s experiences with antipsychotics. Two-thirds (66.9%) of the participants said their experiences with antipsychotic drugs was more negative than positive, with 34.9% stating their experiences were extremely negative. Nearly a quarter (22.1%) of the participants said their experiences were more positive than negative, with 5.7% saying their experiences were extremely positive. The authors said at the point of prescription clinicians should provide a full range of information about antipsychotics, including potential benefits and harms, difficulties withdrawing, and information on alternative treatments, such as psychological therapies.

Implied in the above critique of antipsychotics is the view that psychiatric drugs are psychoactive substances in the same way alcohol or heroin are psychoactive substances. This is what Joanna Moncrieff refers to as the ‘drug-centered’ model of drug action. Conversely, the opening study by Pillinger et al seems to view antipsychotics according to a ‘disease-centered’ model of drug action. Moncreiff said the disease-centered model is borrowed from medicine and presents drugs through the prism of disease, disorder or the symptoms the drugs are thought to treat. The significant effects (or efficacy) are the ones the drugs exert on the diseased or abnormal nervous system. Any others are of secondary interest and referred to as above as side effects or adverse effects.

In contrast, the ‘drug-centred’ model suggests that far from correcting an abnormal state, as the disease model suggests, psychiatric drugs induce an abnormal or altered state. Psychiatric drugs are psychoactive substances, like alcohol and heroin. Psychoactive substances modify the way the brain functions and by doing so produce alterations in thinking, feeling and behaviour. Psychoactive drugs exert their effects in anyone who takes them regardless of whether or not they have a mental condition. Different psychoactive substances produce different effects, however. The drug-centred model suggests that the psychoactive effects produced by some drugs can be useful therapeutically in some situations. They don’t do this in the way the disease-centred model suggests by normalising brain function. They do it by creating an abnormal or altered brain state that suppresses or replaces the manifestations of mental and behavioural problems.

The above discussion suggests individuals being treated with antipsychotics should weigh the risks and benefits of the medication prescribed to them. They need to gather information on their medication, its potential side effects and then monitor how they respond to the drug. This is consistent with what Joanna Moncrieff called the drug-centered model of drug action. The Harrow study also indicated that the use of antipsychotics may not be the best long-term treatment protocol for schizophrenia. If you are using or considering the use of antipsychotics, weigh the pros and cons.