Howard Lotsof said in 1962 while he was having breakfast with a chemist friend of his, the friend began rooting through a freezer, which was full of different psychoactive drugs. “He pulled out a small vial and said, ‘I think you’ll be interested in this.’” Howard asked what it was and the friend said it was an African hallucinogen that lasted 36 hours, so of course he took it. At home he laid down, and it continued to work and work, leaving him exhausted. After 33 hours he thought he would never take ibogaine again, until he realized he was not in narcotic withdrawal. You see, Howard was a 19-year-old heroin addict.

Afterwards, I was walking and I looked at this tree, and as I looked at it, I realized I no longer had any fear of death. Also, that I was no longer addicted to narcotics.

He administered it to a few of his addicted friends, who had similar results. Without withdrawal symptoms, ibogaine appeared to interrupt addiction and provide the user insight into why they used drugs often through ‘visions.’ This began a life-long pursuit of ibogaine as both an “addiction interrupter” and aid to psychotherapy. Despite the interest and research into ibogaine, it remains a Schedule I drug. This means it is illegal to use and difficult to research, within the US.

Psychedelic Times said Dr. Deborah Mash, who has been researching ibogaine for over two decades, thinks moving it from Schedule 1 into Schedule 2 is important for future research with ibogaine. She thought a consortium of credentialed people from academia, and the public and private sector could help stimulate the movement out of Schedule 1. She wants its consumption to be ethical and used for the right purpose. “We have an epidemic of heroin addiction in the US and we need this now more than ever before.”

One of the big barriers for studying ibogaine is that it is in Schedule 1. Ibogaine has no abuse potential. People don’t even like it! Animals don’t self-administer it. We have a way to scientifically look at drugs that might have abuse liability, and ibogaine does not have it. Moving it out of Schedule 1 and into Schedule 2 would open the door for many more people to be able to research it.

Dr. Mash obtained FDA approval to clinically test ibogaine on humans in 1993, but found every grant that she would write for ibogaine was rejected by the NIDA. Scientists at the institute recruited to review the application were concerned about ibogaine’s safety. Frustrated with this catch 22, she found some investors and opened a clinic on St. Kitts, for clinical trials and treatment, the Healing Visions Institute for Addiction Recovery. By 2004, Mash had collected the data she needed to once again approach the FDA, and she closed Healing Visions, which always struggled with money. She said: “This was never run for profit… It was always for research and development.”

Dr. Alberto Solà who was one of the clinicians trained by Dr. Mash at Healing Visions, now owns and operates Clear Sky Recovery, which acknowledges Dr. Mash as a cofounder. The website for Clear Sky Recovery claims, “We are the world’s foremost experts in medically-based ibogaine treatment.” They assert Clear Sky Recovery is the only ibogaine treatment center in the world whose founders are regularly published in peer-reviewed medical journals on the topic “of dosing human, drug dependent individuals with ibogaine.” Watch “Heroin Cure?”, a segment for America Tonight Investigation on the Clear Sky Recovery website, which is linked above, for more information on ibogaine and Clear Sky Recovery.

In “Heroin Cure?” Dr. Mash said at first, she didn’t believe the claims about ibogaine: “How could one molecule have an effect on alcohol, nicotine, cocaine, opiates. It didn’t make sense.” She wanted to see the results firsthand, so she travelled to the Netherlands, where ibogaine trials were going on and watched a detox in action. “I saw people who were at the end of the rope, completely detoxed; looked like new human beings; no signs of withdrawal; and ready to change their life.” She wanted to know what that taught us about the brain, so she organized a clinical trial of ibogaine and received approval from the FDA. It was eventually suspended as the result of no ongoing grant support for the research.

Despite the glowing testimonials on the Clear Sky Recovery website, there are several individuals who are opposed to ibogaine treatment. Dr. Phil Skolnick, a drug development expert at NIDA, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, said he would not recommend it. “Might ibogaine work for some people? It’s absolutely possible. Has its safety and efficacy been established in a rigorous way, absolutely not.” He added there was data in the literature indicating animals administered ibogaine could get brain lesions.

Dr. Mash countered, saying that was exactly why further research was needed and worth doing. She added: “One dose of ibogaine is not going to have toxicity to the brain.” But funding for the necessary research isn’t being offered. Dr. Skolnick, who worked in pharmaceutical companies for several years admitted that addiction medications are rarely embraced. “Pharma has generally been indifferent to addictions; to developing medications to treat addictions.”

Dr. Mash said her intent was to either show that ibogaine worked, or to debunk it. “Either ibogaine works, or it doesn’t. But we in the scientific community need to test, to study. This is too big of a problem, the drug addiction in our society—it’s too large to leave this stone unturned.” She also cautioned that ibogaine has some serious side effects, like cardiac arrest. She was critical of the protocol followed in a MAPS-funded clinical trial in New Zealand, discussed in Part 1, where one of the patients died. She said in an article for Markets Insider,

This recent death underscores the persistent problem associated with the use of ibogaine in unregulated, nonmedical settings by unqualified persons. Ibogaine has complicated pharmacokinetics that contribute to concerns for careful dosing, potential drug interactions, and issues of cardiovascular safety.

A 2006 article in the journal Medical Hypotheses, “Fatalities after taking ibogaine” hypothesized deaths may be the result of cardiac arrhythmias, “caused by a dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system.” Kenneth Alper and others reviewed all the available autopsy reports for known ibogaine-related deaths outside of West Central Africa between 1990 and 2008. The evidence did not suggest a characteristic syndrome of neurotoxicity. Advanced preexisting medical conditions (mainly cardiovascular, and/or one or more typically abused substances) either explained or contributed to the deaths of 12 of 14 cases. “Other apparent risk factors include seizures associated with withdrawal from alcohol and benzodiazepines and the uninformed use of ethnopharmacological forms of ibogaine.”

A 12-minute YouTube showed Dr. Alper giving a report at the ICEERS Ibogaine Conference on the above study. He said the risk factor for ibogaine fatalities were the same as for drug overdose. The risk factors with ibogaine fatalities were: significant preexisting medical, particularly cardiac disease; pulmonary embolisms related to things like travel, immobility within a treatment; using opiates or stimulants during a treatment; and using indigenous forms of uncertain origin and composition, like iboga root bark, by the inexperienced or uninformed patients. He said there was one overriding risk factor for providers. In many cases providers were influenced by someone to do a treatment under circumstances they normally would not; “they bent their own rules.” Dr. Alper believed the widespread adoption of exclusion criteria and pretreatment evaluation before ibogaine treatment; and the inclusion of internists and medical physicians in the pretreatment evaluation were the key factors in decreasing the risk of fatalities with ibogaine.

The mechanism behind the effectiveness of ibogaine is still unknown and the risk factor of sudden, unexplained death during ibogaine treatment is real enough for a report of fatalities to be done at an ibogaine conference held by the International Center for Ethnobotanical Education, Research, and Service (ICEERS). Further research is needed, but is hampered by ibogaine’s classification as a Schedule I drug, and the inconsistent protocols of most centers offering ibogaine treatment. Dr. Mash has expressed concern the adverse effects and unexplained deaths resulting from these treatment centers will hold back any serious consideration by the US research community of ibogaine as an addiction treatment. The stakes are high for the potential help of ibogaine treatment as well as risks for patients. Dr Skolnick said that addicts should not have to face risks with ibogaine in their addiction treatment when they risked so much when actively using. But out of desperation, many addicts are willing to take the risks associated with current ibogaine treatment.

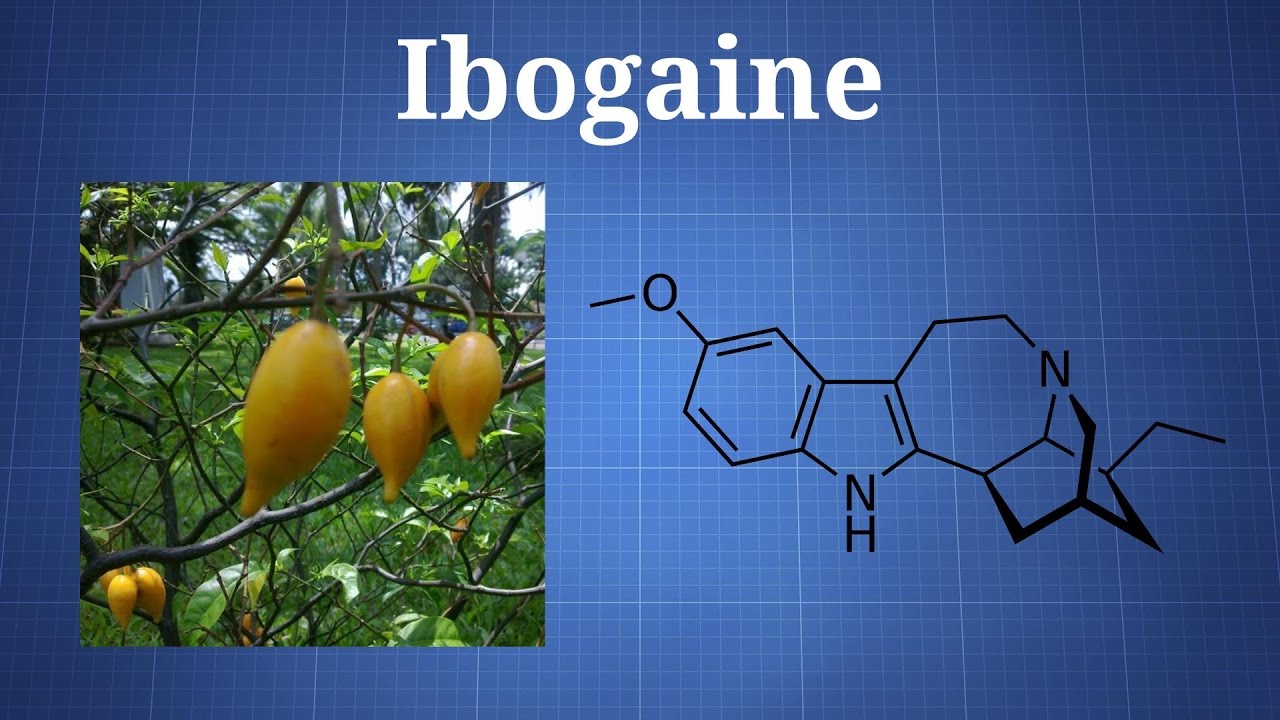

The danger of medical complications with ibogaine for some individuals seems to limit the willingness of the FDA to fund research into ibogaine, despite its promise for treating addiction to multiple substances. The inability of pharmaceutical companies to develop ibogaine into a blockbuster, billion-dollar new molecular entity (NME) because it is an extract of the West African Tabernanthe iboga plant is another reason the research funds are not there. This lack of funding has stymied the scientific, medical investigation of ibogaine. Despite these roadblocks to ibogaine research, it has become a kind of patent medicine touted as a cure all for various addictions. At this time, ibogaine treatment centers necessarily exist outside the US, since ibogaine is a Schedule I substance. There are two registered clinical trials with ibogaine in Brazil, one looking at the safety and tolerability of ibogaine in alcoholic patients; and the other investigating the safety and efficacy of ibogaine for methadone detoxification.

The fact that ibogaine is a hallucinogen, whose effects are likened to waking dreams, is another factor in its failure to attract research funding. Yet many of its advocates view the waking dreams as a crucial part of the ibogaine healing process. Even Dr. Mash, who describes herself as agnostic to the supposed importance of subjective effects of the waking dreams, acknowledged how the therapists she works with believe the hallucinations are part of the healing process with ibogaine. At this point we approach the limits of hard scientific knowledge and the investigation of the neurochemical effects of ibogaine and turn toward its subjective effects, and that of other hallucinogens like psilocybin. Are these molecules a panacea for whatever ails us; or are they more of a placebo effect that will eventually result in a more modest assessment of their potential? We will reflect on this in Part 3.