When James Davies and John Read published a systematic review of antidepressant withdrawal effects in the peer-reviewed journal, Addictive Behaviors, they drew media attention to the growing debate over antidepressant withdrawal. Their findings represented “a public health issue of significant proportions.” After decades of silence, the media attention was surprising. But critiques of their review denied and minimized the problem.

Joseph Hayes and Sameer Jauhar responded to the Davies and Read review on the Mental Elf blog: “Antidepressant withdrawal: reviewing the paper behind the headlines.” Hayes and Sameer said when they looked carefully at the Davies and Read review it did not accurately portray the data. “Whilst withdrawal effects are high for certain drugs (paroxetine, venlafaxine), when stopped abruptly, this happens very rarely in clinical practice and guidelines are in placed to address this.” In response, Davies and Read invited Hayes and Sameer to submit their critique to Addictive Behaviors for a proper peer-review. They also said they disagreed with many of Hayes and Sameer’s arguments:

The fact that there was not more and better research for us to review speaks volumes about whether the prescribing professions have taken the issues seriously. In particular, many of RCT studies employed treatment durations and follow-up protocols that may significantly underestimate withdrawal incidence and duration. Hayes and Jauhar seem particularly concerned about whether our inclusion of surveys may have biased our estimates that 56% experience withdrawal symptoms when coming off and 46% of those describe them as severe. We readily concede, as we did in the review, that our estimates are indeed estimates, based on the best available evidence. They may be off by 5% or even perhaps as much as 10%, lower or higher.

Their estimates were that 56% of those who attempt to come off of antidepressants experience withdrawal. Forty-six percent of those individuals described the effects of withdrawal as severe; and it was not unusual for the withdrawal effects to last for several months. Davies and Read concluded current guidelines underestimated the severity and duration of antidepressant withdrawal.

We recommend that U.K. and U.S.A. guidelines on antidepressant withdrawal be urgently updated as they are clearly at variance with the evidence on the incidence, severity and duration of antidepressant withdrawal, and are probably leading to the widespread misdiagnosing of withdrawal, the consequent lengthening of antidepressant use, much unnecessary antidepressant prescribing and higher rates of antidepressant prescriptions overall. We also recommend that prescribers fully inform patients about the possibility of withdrawal effects.

James and Davies further said using the term ‘discontinuation syndrome’ to characterize antidepressant withdrawal ran contrary to the evidence. The term is misleading, since it wrongly separated antidepressant withdrawal from other CNS (central nervous system) drug withdrawals and minimized the vulnerabilities from SSRIs. Antidepressant withdrawal could occur without discontinuation, for example, with a decrease in medication.

There can also be a misdiagnosis of withdrawal. Re-emergent symptoms of depression and anxiety regularly occur with antidepressant withdrawal and are misread as evidence of a relapse. This leads to drugs being reinstated and a more negative prognosis being used.

Withdrawal can also be misdiagnosed in other ways: as failure to respond to treatment (e.g. where covert non-adherence is mistaken as the condition worsening, leading to dose increase or drug switching); or as bipolar I or II (e.g. where ‘manic’ of ‘hypomanic’ withdrawal reactions are misdiagnosed as the early onset of bipolar); or as the result of switching medications (e.g. where withdrawal reactions are misdiagnosed as side-effects of the new antidepressant).

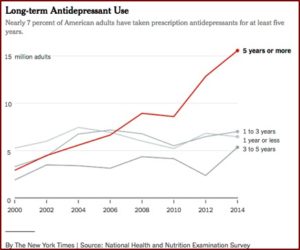

Concern with antidepressant withdrawal led The New York Times to publish two articles: “Many People Taking Antidepressant Discover They Cannot Quit” and “Antidepressant and Withdrawal: Readers Tell Their Stories.” In “Many People,” the authors noted how the long-term use of antidepressants has more than tripled since 2000. Nearly 25 million adults “have been on antidepressants for at least two years, a 60 percent increase since 2010.” The drugs were initially approved for short-term use; to get through a crisis. “Even today, there is little data about their effects on people taking them for years, although there are now millions of such users.”

The Times article looked at data gathered since 1999 as part of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. See the chart below. “‘What you see is the number of long-term users just piling up year after year,’ said Dr. Dr. Mark Olfson, a professor of psychiatry at Columbia University.” Peter Kramer, a psychiatrist and author of books such as: Listening to Prozac, said he thought the decision to use or not use antidepressants was a cultural one—how much depression should someone have to live with? “I don’t think that’s a question that should be decided in advance.”

Antidepressants are not harmless; they commonly cause emotional numbing, sexual problems like a lack of desire or erectile dysfunction and weight gain. Long-term users report in interviews a creeping unease that is hard to measure: Daily pill-popping leaves them doubting their own resilience.

Antidepressants are not harmless; they commonly cause emotional numbing, sexual problems like a lack of desire or erectile dysfunction and weight gain. Long-term users report in interviews a creeping unease that is hard to measure: Daily pill-popping leaves them doubting their own resilience.

In the second NYT article, “Readers Tell Their Stories,” the authors said more than 8,800 people responded to their invitation to tell The Times of their experience with long-term antidepressant use. They said by the mid-1990s drug makers had convinced the FDA that antidepressants reduced the risk of relapse in people with chronic, recurrent depression and should be taken long-term. Then beginning in 1997, pharmaceutical companies were allowed to advertise directly to consumers. This coincided with the popularization of the “chemical imbalance theory” of depression by drug company marketers and some researchers.

In truth, the theory has scant basis. No one knows the underlying biology of depression or any mood disorder. But that shift — along with a change in federal regulations, in 1997, allowing drug makers to advertise directly to consumers — helped undermine the stigma associated with depression and mood disorders generally.

Ronald Pies and David Osser also responded critically to the Davis and Read systematic review in Psychiatric Times, “Sorting Out the Antidepressant ‘Withdrawal’ Controversy.” They said they don’t deny that severe reactions can occur when antidepressants are stopped suddenly, “we also believe that fears of such “excruciating” experiences are greatly overstated, in the context of proper psychiatric care.” Pies and Ossler redirected the blame onto primary care physicians, who prescribe nearly 80% of antidepressants. “Moreover, as critics of these drugs rightly point out, it is very hard to find detailed, professionally approved guidelines for tapering and discontinuation of antidepressants.”

Pies and Osser disagreed with the implication that antidepressants were “addictive” drugs. “We strongly disagree with that characterization and do not believe that SSRI/SNRI discontinuation/withdrawal symptoms should be lumped together with those of clear-cut drugs of abuse, such as alcohol and barbiturates.” They said there was no conclusive evidence of pathophysiological mechanisms underlying SSRI/SNRI withdrawal similar to drugs of abuse such as alcohol, opioids, barbiturates or benzodiazepines. Craving, compulsive use, intentional overuse, and “getting high” are not characteristic of SSRI/SNRI antidepressants.

In their view, the vast majority of serious withdrawal symptoms occurred when the tapering period of SSRIs/SNRIs was less than 1 or 2 months. “This may be particularly the case when the patient has taken the medication for a year or longer.”

We believe, based on our extensive experience with antidepressants, that serious withdrawal symptoms are extremely rare when tapering periods of 2 to 6 months are used. However, we acknowledge that such long tapering periods are probably uncommon in general medical practice, and even in most psychiatric settings.

Davies and Read responded to Pies and Osser in a letter published in Psychiatric Times, “The International Antidepressant Withdrawal Crisis: Time to Act.” They thought Pies and Osser had a biased reading of their systematic review and a selective use of the literature in order to “reassure professionals that antidepressant withdrawal is minimal and easily manageable.” Their opinion was that when clinicians started from the false presumption that a problem was rare, “this can become a self-fulfilling prophecy that minimizes the problem in perpetuity.” They reminded us that in the 1960s and 1970s it was the clinical experience of note psychiatrists that benzodiazepines were not addictive.

They pointed out how the three types of studies in their review did not differ greatly in terms of withdrawal incidence. They gave the weighted averages of each as: 57.1% in online surveys; 52.5% for naturalistic studies; and 50.7% for short randomized controlled trials. Similar findings from the differing methodologies strengthened confidence in the overall estimate. “In fact, findings from the three methodology types demonstrate that it is broadly safe to conclude that at least half of people suffer withdrawal symptoms when trying to come off antidepressants.”

Davies and Read concluded their review by saying antidepressant withdrawal reactions were widespread. Current clinical guidelines in the U.S. and U.K. are in need of correction, “as withdrawal effects are neither mostly ‘mild’ nor ‘self-limiting’ (i.e. typically resolving over 1–2 weeks), but are regularly experienced far beyond what current guidelines acknowledge.” The lengthening duration of antidepressant use has fueled the increase of antidepressant prescriptions over the same time period.

The evidence set out suggests that lengthening use may be partly rooted in the underestimation of the incidence, severity and duration of antidepressant withdrawal reactions, leading to many withdrawal reactions being misdiagnosed, for example, as relapse (with drugs being reinstated as a consequence) or as failure to respond to treatment (with either new drugs being tried and/or dosages increased). This issue is pressing as long-term antidepressant use is associated with increased severe side-effects, increased risk of weight gain, the impairment of patients’ autonomy and resilience (increasing their dependence on medical help), worsening outcomes for some patients, greater relapse rates, increased mortality and the development of neurodegenerative diseases, such as dementia.

Before the Davies and Read review, this debate about antidepressants was largely ignored in the media. But “A systematic review into the incidence, severity and duration of antidepressant withdrawal effects” brought the debate into the media spotlight and demanded a response from conventional psychiatry. On January 23, 2019, Jahaur and Hayes finally published their critique of the Davies and Read review in Addictive Behaviors (as Davies and Read had invited) with the title: “The war on antidepressants.” Sometime afterwards, the article was removed with the following caveat: “The publisher regrets that this article has been temporarily removed. A replacement will appear as soon as possible at which time the reason for the removal of the article will be specified, or the article will be reinstated.”

As of March 16th, when I’m publishing this article, there is no information on why the publisher temporarily removed the article. Michael Hengartner, writing for Mad in America, attempted to explain how the debate turned into such a heated dispute, into a “war.” He traced the origins of the debate back to a February 24, 2018 article to The Times by Wendy Burn and David Baldwin that affirmed: “any unpleasant symptoms experienced on discontinuing antidepressants have resolved within two weeks of stopping treatment.” (See “The Lancet Story on Antidepressants” Part 1 and Part 2 for more). Several academics and psychiatrists, including Davies and Read, challenged the two-week “discontinuation” claim made by Burn and Baldwin. A formal complaint was made to the UK Royal College of Psychiatrists, asserting that the public was being misled over antidepressant safety. Hengartner said:

Given that the biomedical treatment approach constitutes the foundation of modern psychiatry, it was not further surprising that challenging the long-term safety of antidepressants caused discomfort (and, in my view, also disbelief and even denial) within academic psychiatry.

The dispute spilled over into social media, with Jauhar, Hayes and Read trading barbs on Twitter. The Twitter exchanges increased in its aggressive tone, “with ad hominem attacks” made by both sides. Hengartner said he entered the debate in order to point out how Jauhar and Hayes had been exceptionally fierce and reproachful. “In my view, their critique was not only offending, but I also think that some of the most serious charges were unsubstantiated.” Perhaps this tone from Jauhar and Hayes led to “The war on antidepressants” being temporarily removed from the Addictive Behaviors website. “Moreover, the allegation that both the presentation of the results and the conclusions drawn from the data are severely flawed is unwarranted (or at least grossly exaggerated).” His concluding paragraph nicely captured the debate:

Davies and Read put the claim that withdrawal symptoms affect only a small minority and typically resolve within 2 weeks to the test. They provide evidence that withdrawal effects occur in about half of all antidepressant users and that withdrawal is experienced as severe in about half of those concerned. These findings clearly contradict the preferred narrative in mainstream psychiatry. The media widely disseminated these inconvenient findings and soon the review by Davies and Read was fiercely attacked by academic psychiatry in the person of Jauhar and Hayes, who contend that the review was flawed and systematically biased. However, most allegations did not stand up to scrutiny and turned out to be greatly exaggerated or even false. In the interest of the patients who are currently experiencing withdrawal reactions and the many more who will suffer withdrawal effects in the future, we need to end this “war.” Academic psychiatry must address these problems and conduct thorough research on withdrawal reactions. Instead of declaring war, psychiatry should offer solutions on how it wants to combat severe and persistent antidepressant withdrawal. And it is important that psychiatry and clinical psychology reconcile, because, ultimately, we are on the same mission. Our purpose is to help people with mental health problems. Let’s not forget this, even amidst fierce scientific debates.