There are flood stories in addition to that found in the Bible from Ancient Near Eastern (ANE) cultures such as Babylon, Sumer, and Assyria. The Sumerian account is in a text known as the “Eridu Genesis,” which combines a creation story and a flood account. The Babylonian account, known as the Epic of Atrahasis, also combines a creation story and a flood account. A better-known Babylonian version of the flood in the Gilgamesh Epic casts Gilgamesh, a mid-third millennium BC king, as the flood hero. The storyline in all three tells a similar tale.

The above description, and much of what follows, was taken from The Lost World of the Genesis Flood by Tremper Longman and John Walton. In Part 1 of this article we looked at how Longman and Walton suggested the literary use of hyperbole in the Genesis flood account helps suggest why geological science does not support the biblical story of a global flood. Here we look at the similarities and differences of Biblical and ANE flood stories, as well as scientific evidence of a flood that possibly spawned them.

Because of their displeasure with humanity, the gods (at least some of the gods) decide to bring a flood to destroy them. In each case, an individual was saved from the impending destruction through a warning and given instructions to build an ark. The ark’s shape differs in each account. There is a round one in the Epic of Atrahasis (more on this later), a cubical ark in the Gilgamesh Epic, and the oblong ark of Noah. “While the shape of the arks in the various stories differs, remarkably the floor space of the arks is nearly identical.” Ken Ham seems to have taken some creative license by building his Ark Encounter to a slightly larger scale and with more modern looking contours than described here.

After building the ark, the flood hero and others (family and in some cases even more people) as well as animals enter the ark. The flood waters rise and finally ebb to the point that the ark comes to rest. The Gilgamesh Epic and the biblical account note the ark settles on a mountain (Nimush [Nisir] and Ararat, respectively). In these two versions we also hear that Uta-napishti and Noah let out three birds to determine whether the waters had receded to the point that they could disembark. After stepping off the ark, the flood heroes offer a sacrifice to (the) god(s). . . .The flood is understood across all accounts to be motivated by encroaching disorder, and sending the flood represents a strategy to restore order. Though all descriptions are general, each literary reflection provides its own perspective on what constituted the disorder. . . .While the similarities are striking, so are the differences. Indeed, there are so many differences in detail that we won’t mention them all, but they include things like the length and duration of the flood, the size and shape of the ark, the number and identity of people that go on the ark, the name of the flood heroes, and the order of the birds sent out to determine whether the waters of the flood had yet receded.

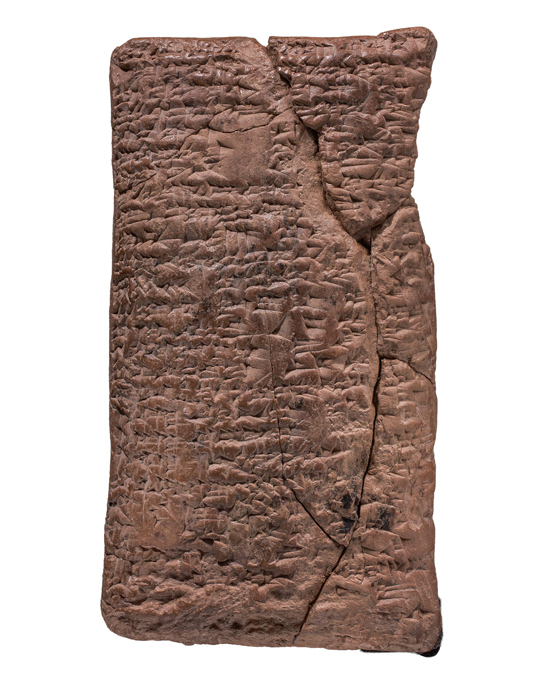

There has been an interesting and recent discovery with regard to the Babylonian flood account. A cuneiform tablet about the size of a cell phone was brought to the attention of Dr. Irving Finkel, Deputy Keeper of Middle East at the British Museum. He is one a handful of experts capable of sight-reading cuneiform. As soon as he saw the tablet he knew it was an account of the Babylonian flood. The front side of the tablet contains a detailed description of the construction of the Babylonian ark, which was a round vessel with a diameter of about 230 feet and 20-foot-high walls. An intriguing detail provided on this tablet was that “the animals enter two-by-two.” Given the detailed description on how Atrahasis was to construct his ark, Finkel resolved to see if he could replicate the process. You can read about his discovery and then watch a forty minute video, “The Real Noah’s Ark,” of his quest on The History Blog: “Noah’s round ark takes to the water.”

The assumptions by Finkel in the video about the biblical text and their dates won’t fit with conservative Christian scholarship. He believed the Epic of Atrahasis was based on an actual flood and that the biblical flood narrative was added to Scripture after the Jews returned from Babylonian captivity in 537 BC. However, The Lost World of the Flood noted excavations at Megiddo unearthed a fragment of the Gilgamesh Epic dating from the time of the Judges (1400 BC to 1050 BC) at the end of the second millennium.

Finkel disregarded the possibility the cuneiform tablet used hyperbole to describe the dimensions of the ark in his attempt to “prove” it could have been seaworthy. His single-mindedness reminded me of Ken Ham wanting to “prove” the truth of the biblical dimensions of Noah’s ark by building the Ark Encounter. Longman and Walton commented that like the biblical ark and the other Mesopotamian arks “this vessel [the round ark of Atrahasis] is inherently not seaworthy.” If you watch the video notice how you can see the bilge pump working to keep the leaking ark afloat at the end of the documentary.

Longman and Walton had a discussion of the difficulty for moderns to understand what an ancient communicator meant because we do not think the same way the communicator did and because elements referred to in the text or story may be foreign to us. Although they were discussing the ancient human communicators of Scripture, what they said has relevance for what seems to have been Finkel’s error with the cuneiform tablet. They said: “A prophet and his audience share a history, a culture, a language, and the experiences of their contemporaneous lives.” If we are to understand Scripture (or any ancient document) rightly, we have to start by putting aside our own cognitive environment or cultural river, “with all our modern issues and perspectives, to understand the cultural river of the ancient intermediaries.”

We can begin to understand the claims of the text as an ancient document by first paying close attention to what the text says and doesn’t say. It is too easy to make intrusive assumptions based on our own culture, cognitive environment, traditions or questions (i.e., our cultural river). It takes a degree of discipline as readers who are outsiders not to assume our modern perspectives and impose them on the text, but often we do not know we are doing it because our own context is so intrinsic to our thinking and the ancient world is an unknown.

In their attempts to replicate the arks described in their respective texts, both Ken Ham and Irving Finkel failed to recognize the use of hyperbole by the ancient authors in their description of their “arks” and the circumstances of the flood. Yet the parallels between ANE flood stories and Genesis 6-8 suggest a common previous event. Could there have been a devastating flood where many people died that generated both the biblical and the ANE flood stories?

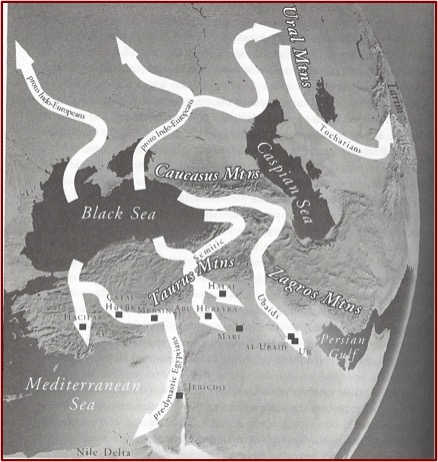

Longman and Walton believe there was a real event behind the flood story just as there was an actual conquest behind the report of Joshua’s campaigns in Joshua 1-12. “We cannot be sure, but we have evidence of more than one flood that would be potential candidates for the inspiration of the story.” They identified one possibility described by William Ryan and Walter Pitman in Noah’s Flood: The New Scientific Discoveries About the Event that Changed History. Ryan and Pitman believe that around 5600 BC a flood from the Mediterranean burst through the Bosporus, pouring saltwater into what had been a freshwater lake four hundred feet below the breached dam in the Bosporus Strait. The modern Black Sea was the result.

Ryan and Pitman suggest that those who survived this flood remembered it as they immigrated to new locations, thus inspiring flood stories that we are aware of among later cultures, including the Babylonian and biblical accounts. We add that each would have taken specific shape according to the cultural and particularly religious beliefs that they had.Ryan and Pitman’s thesis is intriguing. Before they encountered this evidence, they doubted that the biblical flood had any reference to a real historical event. Rather, it was pure myth. Now they believe a real event stands behind the flood story.

The above graphic, found in Noah’s Flood, captures the thesis of Ryan and Pitman. The rising floodwaters flowing through the Bosporus Strait from the Mediterranean Sea (seen at the southwestern corner of the Black Sea) forced the diverse people groups settled around the original fresh water lake to migrate to safer areas. The people groups to the south embedded their experience into the flood stories of the ANE cultures that arose from them. Longman and Walton said: “the literary-theological interpretation of the event is inspired, not the event itself.”

Still, Longman and Walton hesitate to say this particular flood generated the biblical flood story. “We do not believe we can reconstruct the historical event from the biblical account.” Whatever the precise historical event, the story was told from generation to generation and eventually included in the Pentateuch as the story of Noah and the flood.

We don’t think it’s possible to date the event, locate the event, or reconstruct the event in our own terms. That is not a problem because the event itself, with which everyone in the Near East is familiar, is not what is inspired. What is inspired and thus the vehicle of God’s revelation is the literary-theological explanation that is given by the biblical author. . . .The similarities in the telling of the flood story between the Eridu Genesis, Atrahasis, Gilgamesh tablet 11, and the biblical account may be explained not necessarily by literary borrowing but by the fact that this story has been passed down from generation to generation by those who float in the same cultural river.