Every year in December people gather beneath a Downtown Pittsburgh overpass where Grant Street meets Interstate 376 in order to remember the lives of homeless people who died on the streets in the previous year. One of the six bronze-colored plaques fastened to the wall that night held the name of a 23 year-old woman who had attended the memorial the year before. Her plaque joined more than 200 others. Another one of the deaths in 2017 was for a woman whose artwork was shown at a Point Park University art show in 2016. A homeless outreach worker lamented: “The streets take lot of people; they don’t give back; the street’s tough.”

Seven more individuals died in 2017 while in shelters. “Most died of drug overdoses. Most died alone.” One of the speakers at the vigil said it’s about gathering together and saying we care, “but the bigger picture is us gathering together saying that we want zero deaths in the street and we want to end homelessness.” Last year Pittsburgh Mercy’s Operation Safety Net, which sponsors the event, added twelve plaques to the wall. One of those individuals died of a drug overdose in the South Side a day after he helped serve a free community meal for the needy. “He tried to help others with what little he had.”

You can read more about the memorial and see a short video of the 2017 Vigil for the Homeless here on TribLive. Here is a link to Pittsburgh Mercy’s Operation Safety Net. Here is a link to a HomelessShelterDirectory in Pittsburgh.

Annual memorials like this are not the only way individuals can remember and help the homeless. In And This is How It Ends, Jen Sky described how she became involved in ministering to the homeless of Pittsburgh. She started out by serving meals in a park across from Light of Life Mission on the North Side of Pittsburgh and eventually visited homeless camps, interrupted drug deals and witnessed street fights. Her journey began when she messaged a Facebook “friend” who was soliciting others to join with her in helping the homeless. Jen said that conversation on January 11, 2016 “began what could only be called a transformational journey.” The following quote is an excerpt from And This is How It Ends.

It was Jerry’s first day on the streets. Literally, Jerry has a college degree and had been working as a social worker. He had lived with his girlfriend, and her kicking him out coincided with the loss of his job. To my knowledge, Jerry does not have any addictions, but he has some really terrible luck.

Imagine being homeless in Pittsburgh in January or February, when the average low temperature is 20-23 degrees. What if you were unsheltered and had a cold, the flu or pneumonia? And since you weren’t in a shelter of some kind, what if you had to always keep your boots on regardless of how wet they were from the snow?

Once a year, during the last ten days of January, Allegheny County conducts a Point-in Time (PIT) count to identify individuals and families who are homeless. The 2016 Data Brief (the most recent one online) identified 1,156 people who were experiencing homelessness. This was a decrease from a five-year high of 1,573 in 2014. The Data Brief suggested the decrease could be due to Allegheny County’s use of a Rapid-Re-Housing model aimed at helping people experiencing a temporary housing crisis get into permanent housing as quickly as possible.

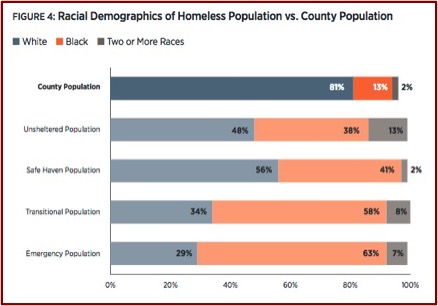

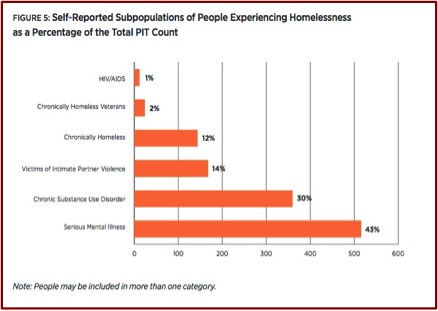

Demographically, there were 673 males and 481 females recorded during the 2016 PIT count. African Americans were disproportionately represented among the homeless. While 13 percent of Allegheny County residents are black, 58 percent of the individuals counted by the 2016 PIT count were black. In addition to being on the streets, the homeless were also experiencing other challenges. Forty three percent had a serious mental health issue; 30% struggled with a chronic substance use disorder; 14% were victims of intimate partner violence. See the following graphics taken from the 2016 Data Brief.

An Australian study by Zaretzky et al., “What drives the high cost of health care costs of the homeless?” noted that people experiencing homelessness “are more likely to experience mental health disorders, long-term physical health conditions and conditions requiring hospital treatment than the general population.” However there seems to be a subpopulation of homeless individuals with very high health care costs. Thirteen percent of the individuals in the study incurred a total health care cost of over $50,000 for the 12-month time period reviewed by the study.

Higher costs were strongly associated with individuals having a diagnosed mental health (MH) disorder (excluding substance use disorders) and/or a long-term physical health condition. Health care costs for these individuals were at least double of those without. Co-occurring MH and substance use disorders were also related to higher health care costs. The very high costs of health care in the study were found to occur with individuals who spent a long time “sleeping rough” (unsheltered).

This finding, and its consistency across two separate and different samples of people experiencing homelessness, provides a significant economic argument for intervention through sustained government programmes targeted to both assist people to manage mental health disorders and long term physical health conditions in a cost-effective and sustainable manner, and to break the cycle of homelessness and maintain stable accommodation.

The latest statistics say that on any given night over 553,000 people experience homelessness in the U.S. Sarah Hunter noted the problem is particularly acute in California, where around 24% of those experiencing homelessness live. LA County has the highest population of unsheltered (living rough) homeless with an estimated 55,000 people—almost 10% of the national total. In an attempt to address this problem, the LA County Department of Health Services launched a program called Housing for Health in 2012. “The program aims to provide long-term, affordable rental housing coupled with intensive case management services that link individuals with the kind of health and social services needed to sustain independent living.”

Instead of requiring participants to first get treatment or receive services, “the LA program offers housing first in an attempt to give participants stability, which in turn helps them benefit more from services.” Hunter and her colleagues studied the impact of the Housing for Health Program on the participants’ health as well as their use and costs of county services. They compared the participants’ use of county services the year before housing and compared it to the use of services one year after being housed.

Permanent supportive housing resulted in a substantial decrease in residents’ use of county services. The use of health care and mental health care dropped the most. LA County’s costs were also down—by nearly 60%. The largest reductions were with the Department of Health, which provides emergency, hospital and outpatient services. There was a reduction of around $20 million after the participants’ first year in the program. For every dollar invested in the Housing for Health program, $1.20 was saved in health care and other social service costs during the participants’ first year.

But based on our research, Los Angeles County’s Housing for Health program addresses an important public health issue by providing housing and supportive services to some of the most vulnerable individuals in our community. The program not only provides the support so that 96 percent remain stably housed, but it also results in a reduction of intensive health care, resulting in a cost savings to taxpayers.

You may not have noticed, but this article shifted its discussion focus from homeless people to the problem of homelessness, beginning with the examination of the Allegheny County Point in Time count. But I think we should conclude by returning our reflections to homeless people. As Jen Sky said in And This is How It Ends, “Homelessness is not a problem. It’s a person.” And we need to see homeless individuals as people created in God’s image and treat them as such. We can attempt to bring people out of the cold and into shelters and other kinds of housing, “but there is nothing we ourselves can do to fix the brokenness inside each of us. That healing needs to come from God.” Jen said:

It has never been easier for me to see God than through my homeless friends. Through their incredible faith, their exceptional fortitude and courage, and through their sheer will and determination to live, I have witnessed a strength and character rarely witnessed in my suburban surroundings. I have seen selflessness and self-sacrifice, courage and perseverance the like of which I had never seen before. They were giving as a sacrifice, not from one’s excess, but giving from subsistence.

Jesus sat and watched people putting money into the offering box in the temple. Many of the rich people put in large sums. But then a poor woman came and put in two small copper coins worth a penny. Jesus called to his disciples and said to them: “Truly, I tell you, this poor widow has put in more than all of them. For they all contributed out of their abundance, but she out of her poverty put in all she had to live on” (Luke 21:3-4). Commenting on these verses in the devotional Connect the Testaments, Rebecca Van Noord noted how the contrast between the Pharisees and the poor woman’s sacrificial giving shows us that “Spiritual wealth can be present where we least expect it.” We can add, even in a homeless person.