A May 1, 2018 research letter in JAMA, “Changes in Synthetic Opioid Involvement in Drug Overdose Deaths,” found that the involvement of synthetic opioids in overdose deaths increased from 14.3% of opioid-related deaths in 2010 to 45.9% in 2016. “Among synthetic opioid-related overdoes deaths in 2016, 79.7% involved another drug or alcohol.” The most common substances were another opioid (47.9%), heroin (29.8%), cocaine (21.6%), prescription opioids (20.9%), benzodiazepines (17.0%), alcohol (11.1%), psychostimulants (5.4%) and antidepressants (5.2%). “Lack of awareness about synthetic opioid potency, variability, availability, and increasing adulteration of the illicit drug supply poses substantial risks to individual and public health.”

Widespread public health messaging is needed, and clinicians, first responders, and lay persons likely to respond to an overdose should be trained on synthetic opioid risks and equipped with multiple doses of naloxone. These efforts should be part of a comprehensive strategy to reduce the illicit supply of opioids and expand access to medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction.

This was the first time synthetic opioids surpassed prescription opioids and heroin as the primary cause of opioid overdose-related deaths. The analysis was limited because 15% to 25% of the death certificates failed to specify which type of drug(s) were involved in the overdose. In “Synthetics now killing more people than prescription opioids, report says,” CNN quoted the lead author of the JAMA report as saying, “So the actual numbers are likely higher.” He added that the findings track closely to the increased availability of illicit synthetic opioids coming into the US.

A senior staff attorney for the nonprofit Drug Policy Alliance commented how synthetic opioids are easier to manufacture than heroin. She also said China was the primary source for illicit fentanyl. “ Illicitly manufactured fentanyl is almost exclusively made in China. . . . It’s then shipped, broadly speaking, to Mexico, where it’s added to the heroin supply before it enters the United States as a cost-saving measure.”

An added concern is while initially synthetic opioids were mixed with heroin, now it’s “mixed with cocaine, methamphetamines and other substances of abuse.” There are also counterfeit tablets containing fentanyl that are made to look like prescription drugs, such as Xanax—made with pill presses shipped from China. See “Buyer Beware Drugs” for more information on this.

In November of 2017 STAT News reported a Chinese official disputed the claim made by President Trump that most of the fentanyl coming to the US was produced in China. He said: “the evidence isn’t sufficient to say that the majority of fentanyl or other new psychoactive substances come from China.” However, both the DEA and the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy previously pointed to China as North America’s main source for fentanyl, related drugs and the precursor chemicals used to make them. Bejing previously regulated fentanyl and 18 related compounds, including carfentanil, furanly fentanyl, acryl fentanyl and valeryl fentanyl.

Then Reuters reported in January of 2018 how a congressional report of a year-long probe by a Senate subcommittee found it was easy for buyers in the US to purchase fentanyl, often in large quantities, from China through the internet. Staff of the committee focused on six “very responsive” providers in China—out of hundreds of pages of website offering fentanyl for sale. The Chinese sellers preferred to ship the fentanyl using Express Mail Service, which operates worldwide through each country’s postal service, including the U.S. Postal Service. “Surcharges are applied, the investigators said, for customers demanding shipment through private delivery services, such as FedEx, DHL and United Parcel Service, because of the greater likelihood the goods would be seized.”

A Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson said she was unaware of the specifics, but that anti-drug coordination was one of the highlights of China-US law enforcement cooperation. “We stand ready to work with the US to enhance our coordination in this field.” The investigators found that the US Postal Service only received the electronic data of just over one-third of all international packages, “making more than 300 million packages in 2017 much harder to screen.” A spokesperson said the Postal Service continues to work to address this issue. Implementing the use of electronic data was slowed by the need to negotiate with international partners.

The Canadian province of Prince Edward Island is slightly larger than the state of Delaware and the only subnational jurisdiction in North America with no mainland territory. Farming is the heart of the province’s economy, which produces 25% of Canada’s potatoes. It consists of the main island (Prince Edward Island) and 231 minor islands. With only around 143,000 residents, it would seem to be one of the last places in North America to be impacted by the fentanyl crisis. But that’s not true any more. In the beginning of May in 2018, the province’s Department of Health reported fentanyl was found in cocaine seized by police in Charlottetown, the capital city of the province.

About the same time Vox reported on the sharp increase of cocaine and fentanyl overdose deaths in the US. Using data from the CDC, Vox found the number of overdose deaths from cocaine and synthetic opioids to be 4,184, 17 times greater than the 245 deaths reported in 2013. Keith Humphreys, from Stanford University, said no one knows for sure what’s going on. “I can tell you my guesses, but I’m pretty sure no one really, honestly knows what’s going on.” Mixing cocaine and fentanyl in a speedball is possible, but the presence of both drugs in a post mortem toxicology report does not mean they were used at the same time. This is the simplest and most plausible explanation, but it wouldn’t apply to the Charlottetown seizure on Prince Edward Island.

A dealer accidentally mixing cocaine and fentanyl, while possible, is even more unlikely. It would have to be a drug operation that buys and sells both cocaine and opioids. Then the individuals cutting the product would have to neglect to clean the space used for cutting the drugs before switching from one drug to the other. But the picture of dumb and dumber drug dealers who just don’t realize what they are doing doesn’t “cut” it.

A third possibility is that dealers or the traffickers above them are purposely mixing cocaine and fentanyl. “With or without the buyer’s knowledge, drug sellers or someone up the chain may be mixing cocaine and fentanyl before the product hits the street.” Two possible reasons would be to give a supposed cocaine product an extra kick; or to get cocaine users hooked on opioids. Experts are skeptical this practice is widespread. Cocaine and fentanyl have opposite drug effects, “which can be unpleasant to someone who wants a pure upper or downer experience.” One expert said the dealer was already making money off the person. “Why would you want to kill them or piss them off?” Yet while this explanation is unlikely and highly speculative, it seems the best explanation for the Charlottetown seizure.

Although what follows is purely speculative, I’d suggest someone intentionally mixed cocaine and fentanyl as an experiment to see if the newer, “edgier” cocaine had a market; it didn’t. Reluctant to waste the drug batch, the trafficker sold it down the supply chain to dealers in Prince Edward Island. If the price was low enough, it may have been that the local dealers didn’t ask too many questions.

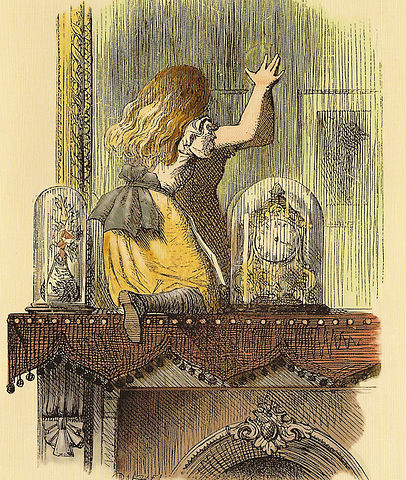

Whatever the true explanation is, individuals using illicit drugs today have stepped through the looking glass into a brave new world where what you get may not be what you thought it was.